SHAW’S telegram said that the interview would take place in a tavern, just off Piccadilly Circus. When I got there Shaw had the room entirely to himself.

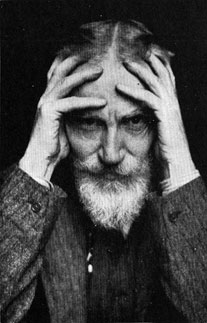

He was half concealed in a huge chair in front of the fireplace. His feet, spread wide apart, rested high up on the mantelshelf. His spine was dug deep into the seat of the chair.

I edged quietly up to a nearby table and looked him over carefully. He was every inch a Brill Brothers production.

“Well,” he said, “I’m going to give you an interview without charging you royalties. In my time I’ve talked on every subject of interest to man or beast. Given the topic or opinion, I have always waited to hear what the world at large says about it; then I know I’m right. The world at large is always wrong. It’s the Irishman’s knack of always being against everything that keeps him right. Do you see?” says he. “I immolate myself, I efface myself in behalf of what the world does not believe. That’s bound to be the truth.”

“That sounds to me,” says I, “like one of those new fangled plays where the program says that the last act begins twenty years before the previous act ends.”

“Never mind them. My plays don’t,” says he. “I’m telling you. With the humility of a martyr one rushes for pen and ink. grabs off a column on the first page of the London Times telling the world what ails it. Then an ungrateful world answers back—whereupon it becomes necessary to tell the truth to the world again—and perhaps again—and so on until one has written enough to fill out an octavo volume at 50 per cent on the gross sales in England—100 per cent. in America.”

“How’s the humility business been since the war started,” says I.

“Bad; very bad,” says Shaw, releasing his feet from the mantelshelf. “It’s a cruel war—I’ve been shoved off the first page of every newspaper that has any kind of a decent circulation.”

“No!” says I.

“Yes!” says he.

“I’M telling you,” says he, “I’ll never forgive the Kaiser so long as I live, though naturally I’m for him in this war—I have to be—everybody else is against him. But he has every right to expect I could make as big a noise as he—with no army to support me. To get any space at all now, I have to hustle around canonizing the Kaiser; but just as I have a masterly article finished and delivered, Winston Churchill begins talking—which is always a signal for a German submarine to torpedo a British dreadnought. War isn’t hell; it is getting space in the newspapers during war-time that’s hell.”

“War for newspaper space is never really war,” says I, “until your copy gets pushed into the back pages among the advertisements. did you ever watch it go? Seen it sink way down among a lot of advertisements of things you never heard of. But when your bright thoughts get placed side by side with a white spaced advertisement that reads, ‘TAKEN BY A FRIEND,’ you’re gone.”

“How do you mean, I’m gone,” says he.

“You’re gone,” says I, “because getting on that page makes you out THE FRIEND. You’ll be billed for that space.”

“Not me,” says he; “anyway, that isn’t the real peril,” says he. “The chief danger is in not being answered. Silence isn’t golden—it’s the bankruptcy proceedings of a talkative man’s fame. There’s just one final way of getting a rise out of the stubborn, stingy editors,” says he.

“Call them reporters,” says I.

“NO,” says he, “I’m telling you. Whenever I feel like a little advertising, I mistake facts that any schoolboy knows. Then somebody has to correct me—and we’re off. lately I wrote ‘If the United States should ever decide to annex Canada AND Alaska on the ground that the Monroe Doctrine obviously requires the extrusion of Britain and Russia from the North American Continent’—just that much; and do you know what happened?”

“What happened?” said I.

“I’m telling you,” says he. “For twenty-four hours, the war was forgotten and everybody in England with a bottle of ink and any kind of a pen was busy setting me right. But by that time I had dropped Canada and Alaska and I was back again giving vegetarianism a helping hand. Up at my house, everybody in our family had to wear mighty large sleeve—the English keep us so busy laughing.”

SAYS I to myself: “This man Shaw is doubling on me; spoofing me, he’d say; so I’ll move off,” says I.

Opposite me, near the window, there was an enormous book on a rickety iron stand. I got up and went over and opened it.

“What are you doing there?” says Shaw.

“I’m reading,” says I.

“What are you reading,” says he.

“The Dictionary,” says I. “It says here,” says I, “Cuttle-Fish,—of the genus Sepis, having an internal shell, large eyes and ten arms, furnished with denticulated suckers, by means of which it secures its prey. It has an ink bag, opening into a siphon, from which when pursued, it throws out a dark liquid that clouds the water, enabling it to escape observation.”

“What does all that add up to?” says Shaw.

“Never mind,” says I, “I’m telling you.”