“Lo, all these seven fears are seven joys,

Whereof the first, where thou did’st see a flag,—

Broad, glorious, gilt with Indra’s badge—cast down

And carried out did signify the end:

For there is change with Gods not less than men

And as the days pass, kalpas pass—at length.”Light of Asia, Book III.

Of all the apocalyptic visions of the ending of the olden days and ways that has ever been declared to humanity, perhaps the strangest—and in a sense the truest—is the story told in the Younger Edda of the coming of Ragnarök, the Day of the Twilight of the Gods. Of old the Æsir, the bright Gods of Day, deemed that they had destroyed all evil in the world. In many a hard-won fight they had overcome the forces of Loki the Evil, Lord of the Nether Fire, and had chained him to the rocks of the nethermost hell, to suffer whilst they caroused in glorious Valhalla, holding themselves secure to all eternity. Alone amongst them Odin the Wise knew that which must be—for had he not pledged his eye to the Norns, that the knowledge of the future might be revealed to his inner vision? But Odin was too wise to mock the joy of the Æsir in their world-sovereignty with the knowledge of the day to come; and so the Gods lived heedless in the Hall of Heaven, deeming that no sorrow could again come nigh them.

But, whilst they fought and drank, the Old World and the Old Order was ever hastening to its doom. Loki, recking not of bonds, nor of the tortures of his rocky bed, was filling the nether world with his offspring; whilst the serpent Nidhogg gnawed ever at the roots of Yggdrasil the World-ash. The longer the Evil One lay chained, the greater ever grew his power, till at last the time should come when, bursting from the bonds wherewith the Gods had fettered him, he should avenge his tortue and his long bondage in a last fearful battle, wherein all Gods, of good and ill alike, should perish in one final and irredeemable struggle. Then the seasons shall fail of their order, and the hearts of men be full of avarice and wrath; brothers shall fight against brothers, and parents slay their children, and at the last there shall be nor spring nor summer, but only an unremitted winter, a horror of cold and twilight over all the earth. Loki and the Fenrir-wolf, breaking the chains with which the Gods had bound them, shall raise all the children of Hel to do battle with the Æsir, and the Death-ship Naglfar shall be floated on the twilight sea.

At last the Gods in Valhalla will perceive—too late—the coming downfall of their empire; and, ceasing from their long oblivion of festival and fight, will sally forth once more over the Bifrost Bridge to wage their last was for the ancient Order of Things. As they ride forth, the Bifrost Bridge will fall in fragments behind htem leaving them no return, and they will meet the awful army of Hel ranged ready to their coming upon Vidgard’s Plain. The Midgard Snake, breathing forth venom and fire, will overwhelm Thor the Hammerer; Odin himself shall be swallowed by the Fenrir-wolf, who in turn shall be slain by Vidar; and Loki shall at last perish under the axe of Heimdal, the Watchman of the Gods.

Then will come Surtur, from whose destroying sword fire spreads on every side, and the flames shall spread throughout the universe, and heaven and earth and hell be crumpled into one smoke-filled chaos, until at last naught shall remain of the Elder World but an illimitable ocean, and silence and obscurity; and the Old Order of Things shall have passed utterly way. All life shall have vanished,—there will be no more on earth the sound of laughter or of tears, nor of any silence of the Gods to mock. Only the Deep Waters, and the Darkness, and the Silence—only these shall reign—an elemental chaos, unredeemed of any life.

Yet not for ever. When the long reign of Darkness shall have passed, a new Sun rising from the East shall shed its light; and from the Deep Waters shall come forth an Island, fair and fertile, and a new life shall be, wherein war and sorrow are unknown; and those who fought for Good of olden times will there take birth anew,—will find anew the Golden Tablets, wherein all wisdom was inscribed of old, and men shall live according to that Law, and there shall be peace and love in all the earth.

Such is the Vision of the Younger Edda:— and to-day in sooth these things are being fulfilled. For the last hundred years the Twilight of the Gods has reigned, no indeed on Vidgard’s Plain, but in the more spacious battle-field of the hearts and lives of men in Western Lands; its warring powers not the old Æsir and the Demons of the Norse Mythology, but the hopes, the ideas, the faiths; the dark ignorances and prejudices, the passions and the base desires of man. Fallen are the ancient Gods that erstwhile reigned in Western hearts, fallen the Old Order of Things,—the chivalries, the despotisms, the animistic beliefs of a hundred years ago are past and gone; and now the destroying fire of Science, like a modern Surtur, mounting aloft even to the distant stars, makes heaven one with earth and leaves behind it but a darkling chaos in the mind of man; the problems of his unanswered, the secret meanings of his being unrevealed;—to his questionings of Why and Whither only an answering silence; to his search for Light only the darkness of an unavailing nescience.

The ancient Gods are fallen,—some yet passing, all must inevitably go. For this new Civilisation of a hundred years is the child of modern Science, and the real rulers of the West are the great workers in the scientific arena. The commerce which has spread this civilisation over all the globe,—that commerce without which England would starve in two month’s time,—is the child of Watt and Stephenson, and of innumerable workers since their time. The food, the clothing, the light, the warmth, the ability to travel in the West are all the gifts of applied Science, and we know not how many industries, born in the scientist’s laboratory and the mechanician’s workshop, have conspired together to bring our Message from the East to the far-distant West to-day. And if these real rulers of the world, the physicist, the engineer, the chemist, the electrician, are agreed on any one thing, that thing is the impossibility of accepting any longer the bases of the old religious beliefs; for in the world which they have investigated with a patience so wonderful, with an analysis so accurate, and a genius so supreme, they have found everywhere only the operations of natural Laws, and have rightly concluded that those beliefs which aforetime constituted the Religions of the West have, in their fundamental doctrine of creation—whether creation of these worlds or of our human souls—no foundation save in the imaginations of their promulgators.

And what the rulers of the West believe, and what they reject or refuse to consider—that, in no long time, the whole Western world will be believing, rejecting, and refusing to consider; and the recent discussions on “Why are the Churches empty?” are perhaps the most eloquent testimony of the effect that the teachings of Science have already had on the religious beliefs of the majority of the people of England. And yet so far—so young is this new Civilisation,—the fundamental teachings of Science, the statements of those natural Laws whereby the physical universe is governed, have really penetrated but little in their convincing fulness into the minds of the masses of the people. When the underlying deduction of Science, that the Universe consists of Phenomena, the resultant of the action of definite Laws, and that all talk of a Noumenon behind such Phenomena is but a vain echo of early animistic beliefs, but an expression of our own ignorance, comes home in its tremendous fulness to the minds of the Peoples of the West, then in proportion to the acceptance of that great generalisation, there will be, there can be, no more adhesion to any form of religious Belief which maintains the existence of a Supreme Noumenon behind all Phenomena, of a Lawgiver behind those Laws, of a Hand whereby these worlds are made.

And so, the West is in a fair way to lose what of Religion it has—that end is inevitable, as inevitable as the progress of Science itself. The forces of Heredity, the old instincts and traditions may for a time suffice to check the stream—but a few generations of widening knowledge will suffice to break down that barrier: and then in the West there can be no more religion—no more religion as past generations comprehended it. If religion were concerned with mere beliefs, if it were a resultant only of untutored animistic views, this would be well indeed, for every atom of wrong views swept from the mind of humanity is gain to all. But it so happens that religion—all religions in varying degrees——contains also one thing that is essential to the well-being of Humanity—the teaching of morality, that ethical basis of life, which lies at the root of all real civilisation; which is the source of the stamina of the Individual, the guardian if the Family, the basis of Civic Duty and the safeguard of the State. Without that ethical basis, without a true morality living and dominant in the hearts and lives of men, the Individual loses that virility of conception and act which alone can render him of service to Humanity; the Family loses its sanctity, with deplorable results on future generations; Civic Duty becomes a synonym for corruption, and the State, its strength sapped by the enervation of its children, hastens towards a final and an irretrievable calamity;—falls, even as fell Imperial Rome, conquered, not indeed by Goth or Hun, but by the decadence of the virtue of its people, by their loss of guiding principle in life; by their want of an Ideal to follow, and their lack of any Hope to come.

And yet the tendency is ever to take religion as a Religion, to regard it as an integral whole, as a thing which must stand or fall together in all its parts,—ethic and belief together, good and bad alike; and signs are now not wanting that, with the undermining by the spread of scientific knowledge of the old-time beliefs, that portion of the Christian Religion which is the only thing of any real value in it to Religion which is the only thing of any real value in it to Humanity—its ethic code—is also losing its hold on the minds of men in Western lands. If the churches are empty, the taverns are full; if laws for the restraint of crime are multiplied each year, so also are the gaols; if education is increasing on every hand, so also is insanity; and, if we set aside such general calamities as plagues and famines, there is more real poverty, more starvation, more utter misery in England and America to-day than yet exists in any Buddhist land, where the people are poorer indeed in this world’s goods, but richer, incomparably richer, in that trained attitude of mind, born of a deep appreciation of the realities of existence and of a cultured æstheticism, which alone can one rise to true contentment, to mental peace, to a happiness which finds its goal rather in the inalienable delights of the exercise of the higher mental faculties, than in the possession of innumerable means of advancing wealth and commerce, of gratifying sense and avarice, of promoting merely bodily comforts.

And surely herein lies the right aim of all Civilisation, the true test of the value of any effort after progress, whether it be called Civilisation or Religion or Philosophy:—does that system, in tis application, tend to promote the general welfare of man; to enlarge their hearts with love, to expand their mental horizon; does it diminish the world’s misery, its poverty, its criminality; does it, in a single word, increase the happiness of those who pursue it? Is any one in doubt of the answer which must be given to this question, as applied to the modern civilisation of the West? Apart altogether from the misery that that civilisation has spread in lands beyond its pale, can it be claimed that in its internal polity, that for its own peoples, it has brought with it any diminution of the world’ls suffering, any diminution of its degradation, its misery, its crime; above all, has it brought about any general increase of its native contentment, the extension of any such knowledge as promotes the spirit of mutual helpfulness rather than the curse of competition;—has it brought to the peoples of the West a lasting increase of mental peace, of solidarity, of deep and enduring happiness?

The voices of the vast armies of the Powers—ten million men torn from the useful service of humanity in field or factory or State, trained in the arts of death and devastation, waiting but a word to let Hell loose on earth,—these have answered! Have that modern enlightenment has failed,—how bitterly those millions testify,—to increase those virtues of solidarity whereon alone a lasting progress can be built. Each year sees new millions of the nations’ wealth wasted in munitions of war, each year new millions accrue to the revenues of the Powers from the State-protected traffic in that drink that is undermining the health, the mental equilibrium, the lives of the children of the State; and surely these things, as also these crowded taverns, these overflowing gaols, these sad asylums have added their testimony:—is not their answer also ’No‘?

Great, indeed, has been the boon that modern science and the modern civilisation has conferred upon the world. It has immeasurably improved our knowledge of the world about us, it has created a system of commerce and communication unparalleled in the history of mankind; its governments, in their internal administration, are a vast advance on those of ancient days; its justice is to a great extent beyond corruption, its capacity for coöperation and organization beyond all cavil. But, with these great virtues, these things that have made it great, has there come increase of happiness to the masses of the people?—That is the great question on the answer to which a civilisation must be judged. And if the answer, as we think, is No, then what is the reason for the failure that answer implies—what is the cure the ever-growing misery, the stress and turmoil of the modern life?

We would answer that the cause of that failure lies, firstly in the steady disappearance of the ethical basis of life before the attacks of Science on Revealed Religion; and secondly that the energies of the Western Civilisation have turned in a direction from which no final satisfaction can be gained;—we would answer that the cure for somewhat at least of the burden of modern life lies in the adoption of an ethical system not based on revelation,—lies in the realisation of material possessions, but on the culture of the higher faculties of the mind. In other words, there is need in the West to-day of a Religion which shall contain in the highest degree a philosophy, a system of ontology, founded on Reason rather than upon Belief; a Religion containing the clearest possible enunciation of ethical principles; a Religion which shall be devoid of those animistic speculations which have brought about the downfall of the hereditary faiths of the West, devoid of belief in all that is opposed to reason,—a Religion which shall proclaim the Reign of Law alike in the world of Matter, and in the world of Mind.

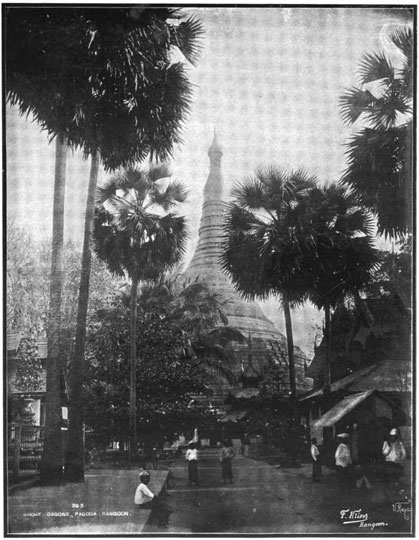

Such a Religion exists,—a Religion unparalleled in the purity of its ethical teaching, unapproached in the sublimity of its higher doctrine; a Religion which, more than any other in the world, has served to civilise, to uplift, to elevate, to promote the happiness of mankind; a Religion whose proudest boast it is that its altars are unstained by one drop of human blood;—the Religion of the Law of Truth proclaimed by the Great Sage of India, the knowledge and the practise of which has brought peace into the lives of innumerable men. Tested by the lapse of twenty-five centuries, by the lives of eighty generations of men, that Religion is yet the solace and the hope of a third of humanity; it has been the Faith of forgotten ages, it is to-day the greatest of the World-religions:—it will be the Faith of the Future in that far distant time, when all mankind, conquered by the Love it teaches, enlightened by the Truth it holds, shall dwell at last in harmony, in self-restraint, in mutual forbearance:—shall attain at last to a true Civilisation; to a happiness beyond our hopes, who live but in the childhood of humanity; to a knowledge far beyond our deeming, as the stars beyond our earthlit lamps; in that day when the Flower of our Humanity shall have blossomed in the Light to Come, filling all earth with yet unmanifested glory,—suffusing all the hearts of men with the perfume of its utter Peace.