Hypnotherapy

An Exploratory Casebook

by

Milton H. Erickson

and

Ernest L. Rossi

With a Foreword by Sidney Rosen

IRVINGTON PUBLISHERS, Inc., New York

Halsted Press Division of

JOHN WILEY Sons, Inc.

New York London Toronto Sydney

The following copyrighted material is reprinted by permission:

Erickson, M. H. Concerning the nature and character of post-hypnotic behavior. Journal of General Psychology, 1941, 24, 95-133 (with E. M. Erickson). Copyright © 1941.

Erickson, M. H. Hypnotic psychotherapy. Medical Clinics of North America, New York Number, 1948, 571-584. Copyright © 1948.

Erickson, M. H. Naturalistic techniques of hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1958, 1, 3-8. Copyright © 1958.

Erickson, M. H. Further clinical techniques of hypnosis: utilization techniques. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1959, 2, 3-21. Copyright © 1959.

Erickson, M. H. An introduction to the study and application of hypnosis for pain control. In J. Lassner (Ed.), Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine: Proceedings of the

International Congress for Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine. Springer Verlag, 1967. Reprinted in English and French in the Journal of the College of General Practice of Canada, 1967, and in French in Cahiers d' Anesthesiologie, 1966, 14, 189-202. Copyright © 1966, 1967.

Copyright © 1979 by Ernest L. Rossi, PhD

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission from the publisher. For information, write to Irvington Publishers, Inc., 551 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10017.

Distributed by HALSTED PRESS

A division of JOHN WILEY SONS, Inc., New York

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Erickson, Milton H. Hypnotherapy, an exploratory casebook.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Hypnotism - Therapeutic use. I. Rossi, Ernest Lawrence, joint author. II. Title. RC495.E719 615.8512 78-23839 ISBN 0-470-26595-7

Printed in The United States of America

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Chapter 1. The Utilization Approach to Hypnotherapy

1. Preparation

2. Therapeutic Trance

3. Ratification of Therapeutic Change Summary Exercises

Chapter 2. The Indirect Forms of Suggestion

1. Direct and Indirect Suggestion

2. The Interspersal Approach

a) Indirect Associative Focusing

b) Indirect Ideodynamic Focusing

3. Truisms Utilizing Ideodynamic Processes

a) Ideomotor Processes

b) Ideosensory Processes

c) Ideoaffective Processes

d) Ideocognitive Processes

4. Truisms Utilizing Time

5. Not Knowing, Not Doing

6. Open-Ended Suggestions

7. Covering All Possibilities of a Class of Responses

8. Questions That Facilitate New Response Possibilities

a) Questions to Focus Associations

b) Questions in Trance Induction

c) Questions Facilitating Therapeutic Responsiveness

9. Compound Suggestions

a) The Yes Set and Reinforcement

b) Contingent Suggestions and Associational Networks

c) Apposition of Opposites

d) The Negative

e) Shock, Surprise, and Creative Moments

10. Implication and the Implied Directive a) The Implied Directive

11. Binds and Double Binds

a) Binds Modeled on Avoidance-Avoidance and Approach-Approach Conflicts

b) The Conscious-Unconscious Double Bind

c) The Double Dissociation Double Bind

12. Multiple Levels of Meaning and Communication: The Evolution of Consciousness in Jokes, Puns, Metaphor, and Symbol Exercises

Chapter 3. The Utilization Approach: Trance Induction and Suggestion

1. Accepting and Utilizing the Patient's Manifest Behavior

2. Utilizing Emergency Situations

3. Utilizing the Patient's Inner Realities

4. Utilizing the Patient's Resistances

5. Utilizing the Patient's Negative Affects and Confusion

6. Utilizing the Patient's Symptoms Exercises

Chapter 4. Posthypnotic Suggestion

1. Associating Posthypnotic Suggestions with Behavioral Inevitabilities

2. Serial Posthypnotic Suggestions

3. Unconscious Conditioning as Posthypnotic Suggestion

4. Initiated Expectations Resolved Posthypnotically

5. Surprise As a Posthypnotic Suggestion Exercises

Chapter 5. Altering Sensory-Perceptual Functioning: The Problem of Pain and Comfort

Case 1. Conversational Approach to Altering Sensory-Perceptual Functioning: Phantom Limb Pain and Tinnitus

Case 2. Shock and Surprise for Altering Sensory-Perceptual Functioning: Intractable Back Pain

Case 3. Shifting Frames of Reference for Anesthesia and Analgesia

Case 4. Utilizing the Patient's Own Personality and Abilities for Pain Relief

Selected Shorter Cases: Exercises for Analysis

Chapter 6. Symptom Resolution

Case 5. A General Approach to Symptomatic Behavior

Session One:

Part One. Preparation and Initial Trance Work

Part Two. Therapeutic Trance as Intense Inner Work

Part Three. Evaluation and Ratification of Therapeutic Change

Session Two: Insight and Working Through Related Problems

Case 6. Demonstrating Psychosomatic Asthma with Shock to Facilitate Symptom Resolution and Insight

Case 7. Symptom Resolution with Catharsis Facilitating Personality Maturation: An Authoritarian Approach

Case 8. Sexual Dysfunction: Somnambulistic Training in a Rapid Hypnotherapeutic Approach

Part One. Facilitating Somnambulistic Behavior

Part Two. A Rapid Hypnotherapeutic Approach Utilizing . Therapeutic Symbolism with Hand Levitation

Case 9. Anorexia Nervosa Selected Shorter Cases. Exercises for Analysis

Chapter 7. Memory Revivication

Case 10. Resolving a Traumatic Experience

Part One. Somnambulistic Training, Autohypnosis, and Hypnotic Anesthesia

Part Two. Reorganizing Traumatic Life Experience and Memory Revivication

Chapter 8. Emotional Coping

Case 11. Resolving Affect and Phobia with New Frames of Reference

Part One. Displacing a Phobic Symptom

Part Two. Resolving an Early-Life Trauma at the Source of a Phobia

Part Three. Facilitating Learning: Developing New Frames of Reference

Selected Shorter Cases: Exercises for Analysis

Chapter 9. Facilitating Potentials: Transforming Identity

Case 12. Utilizing Spontaneous Trance: An Exploration

Integrating Left and Right Hemispheric Activity

Session 1: Spontaneous Trance and its Utilization: Symbolic Healing

Session 2: Part One. Facilitating Self-Exploration

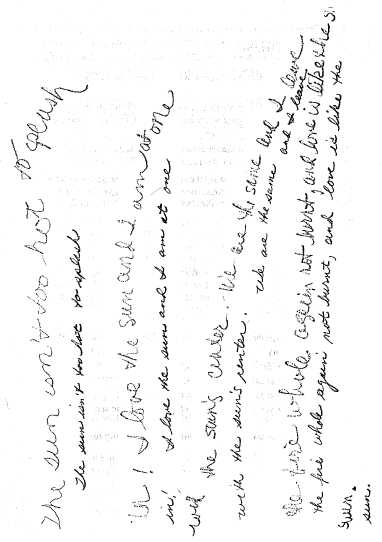

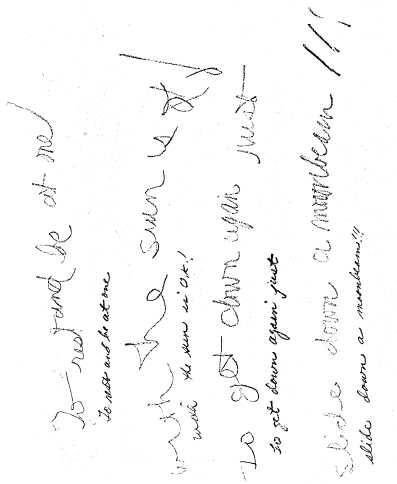

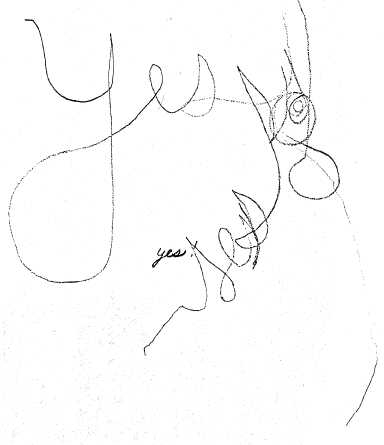

Part Two. Automatic Handwriting and Dissociation

Case 13. Hypnotherapy in Organic Spinal Cord Damage: New Identity Resolving Suicidal Depression

Case 14. Psychological Shock and Surprise to Transform Identity

Case 15. Experiential Life Review in the Transformation of Identity

Chapter 10. Creating Identity: Beyond Utilization Theory?

Case 16. The February Man

References

Foreword

Speak to the wall so the door may hear - Sufi saying.

Everyone who knows Milton Erickson is aware that he rarely does anything without a purpose. In fact, his goal-directedness may be the most important characteristic of his life and work.

Why is it, then, that prior to writing Hypnotic Realities with Ernest Rossi (Irvington, 1976) he had avoided presenting his work in book form? Why did he choose Ernest Rossi to coauthor that book and the present one? And, finally, I could not help but wonder, Why did he ask me to write this foreword?

Erickson has, after all, published almost 150 articles over a fifty-year period, but only two relatively minor books - Time Distortion in Hypnosis, written in 1954 with L. S. Cooper, and The Practical Applications of Medical and Dental Hypnosis, in 1961 with S. Hershman, MD and I. I. Sector, DDS. It is easy to understand that in his seventies he may well be eager to leave a legacy, a definitive summing up, a final opportunity for others to really understand and perhaps emulate him.

Rossi is an excellent choice as a coauthor. He is an experienced clinician who has trained with many giants in psychiatry - Franz Alexander, amongst others. He is a Jungian training analyst. He is a prolific author and has devoted the major part of his time over the past six years to painstaking observation, recording and discussion of Erickson's work.

Again, Why me? I am also a training analyst, but with a different group - the American Institute of Psychoanalysis (Karen Horney). I have been a practicing psychiatrist for almost thirty years. For almost fifteen years I have also done a great deal of work with disabled patients. I have been involved with hypnosis for over thirty-five years, since I first heard about Milton Erickson, who was then living in Eloise, Michigan.

Both Rossi and I have broad, but differing, clinical and theoretical backgrounds. Neither of us has worked primarily with hypnosis. Therefore, neither of us has a vested interest in promoting some hypnotic theories of our own. We are genuinely devoted to the goal of presenting Erickson's theories and ideas, not only to practitioners of hypnosis, but to the community of psychotherapists and psychoanalysts which has had little familiarity with hypnosis. Towards this end, Rossi assumes the posture of a rather naive student acting on behalf of the rest of us.

Margaret Mead, who also counts herself as one of his students, writes of the originality of Milton Erickson in the issue of The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis dedicated to him on his seventy-fifth birthday (Mead, M. The Originality of Milton Erickson, AJCH, Vol. 20, No. 1, July 1977, pp. 4-5). She comments that she has been interested in his originality ever since she first met him in the summer of 1940, expanding on this idea by stating, It can be firmly said that Milton Erickson never solved a problem in an old way if he can think of a new way - and he usually can. She feels, however, that his unquenchable, burning originality was a barrier to the transmission of much of what he knew and that inquiring students would become bemused with the extraordinary and unexpected quality of each different demonstration, lost between trying to imitate the intricate, idiosyncratic response and the underlying principles which he was illuminating. In Hypnotic Realities and in this book, Ernest Rossi takes some large steps towards elucidating these underlying principles. He does this most directly by organizing and extracting them from Erickson's case material. Even more helpfully, though, he encourages Erickson to spell out some of these principles.

Students who study this volume carefully, as I did, will find that the authors have done the best job to date in clarifying Erickson's ideas on the nature of hypnosis and hypnotic therapy, on techniques of hypnotic induction, on ways of inducing therapeutic change, and of validating this change. In the process they have also revealed a great deal of helpful data about Erickson's philosophy of life and therapy. Many therapists, both psychoanalytic and others, will find his approaches compatible with their own and far removed from their preconceptions about hypnosis. As the authors point out, Hypnosis does not change the person nor does it alter past experiential life. It serves to permit him to learn more about himself and to express himself more adequately. . . . Therapeutic trance helps people side-step their own learned limitations so that they can more fully explore and utilize their potentials.

Those who read Erickson's generous offering of fascinating case histories, and then attempt to emulate him, will undoubtedly find that they do not achieve results that are at all comparable to his. They may then give up, deciding that Erickson's approach is one that is unique for him. They may note that Erickson has several handicaps that have always set him apart from others, and that may certainly permit him to have a unique way of viewing and responding. He was born with color deficient vision, tone deafness, dyslexia, and lacking a sense of rhythm. He suffered two serious attacks of crippling poliomyelitis. He has been wheelchair bound for many years from the effects of the neurological damage, supplemented by arthritis and myositis. Some will not be content with the rationalization that Erickson is a therapeutic or inimitable genius. And they will find that with the help of clarifiers and facilitators, such as Ernest Rossi, there is much in his way of working that can be learned, taught and utilized by others.

Erickson himself has advised, in Hypnotic Realities (page 258), In working at a problem of difficulty, you try to make an interesting design in the handling of it. That way you have an answer to the difficult problem. Become interested in the design and don't notice the back-breaking labor. In dealing with the difficult problem of analyzing and teaching Erickson's approaches, Rossi's designs can be most helpful. Whether each reader will choose to accept Rossi's suggestion that he practice the exercises recommended in this book, is an individual matter; in my experience, it has been worthwhile to practice some of them. In fact, by deliberately and planfully applying some of Erickson's approaches as underlined by Rossi, I found that I have been able to help patients experience deeper states of trance and be more open to changing as an apparent consequence of this. I found that setting up therapeutic double binds, giving indirect posthypnotic suggestions, using questions to facilitate therapeutic responsiveness, and building up compound suggestions have been particularly helpful. Erickson and Rossi's repeated emphasis on what they call the utilization approach is certainly justified. In this book they give many vivid and useful examples of accepting and utilizing the patient's manifest behavior, utilizing the patient's inner realities, utilizing the patient's resistances, and utilizing the patient's negative affect and symptoms. Erickson's creative use of jokes, puns, metaphors and symbols has been analyzed by others, notably Haley and Bandler and Grinder, but the examples and discussion in this book add a great deal to our understanding.

At times, Erickson will work with a patient in a light trance, in what he calls a common everyday trance, or no trance at all. He does not limit himself to short-term therapy. This is illustrated in his painstaking work over a nine-month period with Pietro, the flutist with the swollen lip, described in one of the dramatic case outlines in this book. His expertise, however, in working with patients in the deepest trances, often with amnesia for the therapeutic work, has always interested observers. The question of whether or not inducing deeper trances, and giving directions or suggestions indirectly rather than directly, leads to more profound or lasting clinical results is a researchable one. It has certainly been my experience that if one does not believe in, or value, deeper trances and does not strive for them, one is not likely to see them very often. My experience has also been that the achievement of deeper trances, often including phenomena such as dissociation, time distortion, amnesia, and age-regression, does lead to quicker and apparently more profound changes in patients' symptoms and attitudes.

Erickson emphasizes the value of helping patients to work in the mode of what he would call the unconscious. He values the wisdom of the unconscious. In fact, he often goes to great lengths to keep the therapeutic work from being examined and potentially destroyed by the patient's conscious mind and by the patient's learned and limited sets. His methods of doing this are more explicitly outlined in this book than in any other writings available to date.

It is true that he tends not to distinguish between induction of trance or hypnotic techniques and therapeutic techniques or maneuvers. He feels that it is a waste of time for the therapist to use meaningless, repetitious phrases in the induction of trance as this time might be more usefully employed injecting therapeutic suggestions or in preparing the patient for change. As Rossi has pointed out, both the therapy and trance, induction involve, in the early stages, a depotentiation of the patient's usual and limited mental sets. Erickson is never content with simply inducing a trance, but is always concerned with some therapeutic role.

He points out the limited effectiveness of direct suggestion, although he is certainly aware that hypnotic techniques, using direct suggestion, will frequently enhance the effectiveness of behavior modification approaches such as desensitization and cognitive retraining. He notes that Direct suggestion . . . does not evoke the re-association and reorganization of ideas, understandings and memories so essential for an actual cure . . . Effective results in hypnotic psychotherapy . . . derive only from the patient's activities. The therapist merely stimulates the patient into activity, often not knowing what that activity may be. And then he guides the patient and exercises clinical judgment in determining the amount of work to be done to achieve the desired results (Erickson, 1948). From this comment, and from reading the case histories in this volume and in other publications, it should be apparent that Erickson demands and evokes much less doctrinal compliance than do most therapists.

It is obvious that clinical judgment comes only as the result of many years of intensive study of dynamics, pathology and health, and from actually working with patients.

The judgment of the therapist will also be influenced by his own philosophy and goals in life. Erickson's own philosophy is manifested by his emphasis on concepts such as growth and delight and joy . To this he adds, Life isn't something you can give an answer to today. You should enjoy the process of waiting, the process of becoming what you are. There is nothing more delightful than planting flower seeds and not knowing what kinds of flowers are going to come up. My own experience in this regard is illustrated by my having visited him in 1970, spending a four-hour session with him, and leaving with the feeling that I had spent this time mostly in listening to stories about his family and patients. I did not see him again until the summer of 1977. Then, at 5:00 a.m. in a Phoenix motel, while I was reviewing some tapes of Erickson at work, some very important insights became vividly evident to me. They were obviously related to work begun during our session in 1970 and to self analysis I had done in the intervening seven years. Later that morning when I excitedly mentioned these insights to Erickson, he, typically, simply smiled and did not attempt to elaborate on them in any way.

When we read some of the writings on other forms of therapy, such as family therapy or Gestalt therapy, we are struck by how much they have been influenced by Erickson. This is no accident as many of the early therapists in these schools began working with hypnosis or even with Erickson himself. I hope that Rossi will trace some of these influences in his future writings. I have alluded to some of them in my article, Recent Experiences with Encounter Gestalt and Hypnotic Techniques (Rosen, S. Am J. Psychoanalysis, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1972, pp. 90-105).

In conjunction with Erickson and Rossi's first volume Hypnotic Realities, Hypnotherapy: An Exploratory Casebook should serve as a firm basis for courses in Ericksonian therapy or Ericksonian hypnosis. These courses may be supplemented by other books, including those written by J. Haley and by Bandler and Grinder. In addition, we are now fortunate to have available a bibliography of the 147 articles written by Erickson himself (see Gravitz, M.A. and Gravitz, R. F., Complete Bibliography 1929-1977,'' American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1977, 20, 84-94).

Rossi has told me that in working with Erickson he has always been struck by the fact that Erickson seems to be atheoretical. I have noted that this applies to Erickson's openness but certainly not to his emphasis on growth or his humanistic or socially oriented views. Rossi and others are constantly rediscovering the fact that Erickson always works towards goals - those of his patients', not his own. This may not seem to be such a revolutionary idea today when it is the avowed intention of almost all therapists, but perhaps many of us are limited in our capacity to carry out this intent. It is significant that both intent and practice are most successfully coordinated and realized in the work of this man who is probably the world's master in clinical hypnosis, and yet hypnosis is still associated by almost everyone with manipulation and suggestion - a typical Ericksonian paradox. The master manipulator allows and stimulates the greatest freedom!

Sidney Rosen, MD

New York

Preface

The present work is the second in a series of volumes by the authors that began with the publication of Hypnotic Realities (Irvington, 1976). Like that first volume, the present work is essentially the record of the senior author's efforts to train the junior author in the field of clinical hypnotherapy. As such, the present work is not of an academic or scholarly nature but rather a practical study of some of the attitudes, orientations, and skills required of the modern hypnotherapist.

In the first chapter we outline the utilization approach to hypnotherapy as the basic orientation to our work. In the second chapter we essay a more systematic presentation of the indirect forms of suggestion, which were originally selected out of the case presentations of our first volume. We now believe that the utilization approach and the indirect forms of suggestion are the essence of the senior author's therapeutic innovations over the past fifty years and account for much of his unique skill as a hypnotherapist.

In Chapter Three we illustrate how the utilization approach and the indirect forms of suggestion can be integrated to facilitate the induction of therapeutic trance in a manner that simultaneously orients the patient toward therapeutic change. In our fourth chapter we illustrate the approaches to posthypnotic suggestion that the senior author has found most effective in day-to-day clinical practice.

These first four chapters outline some of the basic principles of the senior author's approach. We hope this presentation will provide other clinicians with a broad and practical perspective of the senior author's work and serve as a source of hypotheses about the nature of therapeutic trance that will be tested with more controlled experimental studies by researchers.

At the end of each of these first four chapters we have suggested a number of exercises to facilitate learning the orientation, attitudes, and skills required of anyone who wants to put some of this material into actual practice. A simple reading and understanding of the material is not enough. An extensive effort to acquire new habits of observation and interpersonal interaction are required. All the suggested exercises have been put into practice as we have sought to hone our own skills and teach others.

Each of the remaining six chapters presents case studies illustrating and further exploring the senior author's clinical work with patients. Six of these cases (cases 1,5,8,10,11, and 12) are major studies like those in our first volume, Hypnotic Realities, where we transcribed tape recordings of the senior author's actual words and patterns of interaction with patients. The recording equipment for these studies was provided by a research grant from the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis - Education and Research Foundation. In our commentaries on these sessions we have presented our current understanding of the dynamics of the hypnotherapeutic process and discussed a number of issues such as the facilitation of the creative process and the functions of the left and right hemispheres.

Most of the other shorter cases were drawn from the senior author's file of unpublished records of his work in private practice, some of them from long-unopened folders containing yellowed pages more than a quarter of a century old. These cases were all reviewed and re-edited with fresh commentaries and provide an appropriate perspective on the spontaneous creativity and daring required of the hypnotherapist in clinical practice. In addition, we have skimmed through many tape recordings of the senior author's lectures and workshops at the meetings of the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis. Some of these were already typed and partially edited by Florence Sharp, Ph.D., and other members of the Society. Most of these appear under the heading Selected Shorter Cases: Exercises for Analysis. Many of them have been repeated and published so often (Haley, 1973) that they appear anecdotal, as part of the folklore of hypnosis in the past half-century. They can serve as marvelous exercises for analysis, however. At the end of each such case we have placed in italics some of the principles we feel were involved. The reader may enjoy finding others.

It is our impression that the clinical practice of hypnotherapy is currently emerging from a period of relative quiescence into an exciting time of new discoveries and fascinating possibilities. Those who know the history of hypnosis are already familiar with this cyclic pattern of excitement and quiescence that is so characteristic of the field. Some historians of science now believe this cyclic pattern is characteristic of all branches of science and art: The excitement comes with periods of new discovery, the quiescence comes as these are assimilated. As the junior author gradually put this volume together, he frequently had a subjective sense of new discovery. But was it new only for him, or would it be new for others as well? We must rely upon you, our reader, to make an independent assessment of the matter and perhaps carry the work a step further.

Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Ernest L. Rossi, Ph.D.

Acknowledgments

This work can be recognized as a truly community effort, with many more individuals contributing to it than we can acknowledge by name. First among these are our patients, who frequently recognized and cooperated with the exploratory nature of our work with them. Their spontaneous creativity is truly the basis of all innovative therapeutic work: We simply report what they learned to do with the hope that their success may be a useful guide for others.

Many of the teachers and participants in the seminars and workshops of the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis have provided a continual series of insights, illustrations, and comments that have found their way into this work. Prominent among these are Leo Alexander, Ester Bartlett, Franz Baumann, Neil D. Capua, David Cheek, Sheldon Cohen, Jerry Day, T. E. A. Von Dedenroth, Roxanne and Christie Erickson, Fredericka Freytag, Melvin Gravitz, Frederick Hanley, H. Clagett Harding, Maurice McDowell, Susan Mirow, Marion Moore, Robert Pearson, Bertha Rodger, Florence Sharp, Kay Thompson, Paul Van Dyke, M. Erik Wright.

To Robert Pearson we owe a special acknowledgment for having first suggested the basic format of this work, for his continual encouragement during its gestation, and for his critical reading of our final draft. Ruth Ingham and Margaret Ryan have contributed significant editing skills that finally enabled our work to reach the press.

Finally, we wish to acknowledge the following publishers who have generously permitted the republication of five of the papers in this volume: American Society of Clinical Hypnosis, Journal Press, W. B. Saunders Company, and Springer Verlag.

CHAPTER 1

The Utilization Approach to Hypnotherapy

We view hypnotherapy as a process whereby we help people utilize their own mental associations, memories, and life potentials to achieve their own therapeutic goals. Hypnotic suggestion can facilitate the utilization of abilities and potentials that already exist within a person but that remain unused or underdeveloped because of a lack of training or understanding. The hypnotherapist carefully explores a patient's individuality to ascertain what life learnings, experiences, and mental skills are available to deal with the problem. The therapist then facilitates an approach to trance experience wherein the patient may utilize these uniquely personal internal responses to achieve therapeutic goals.

Our approach may be viewed as a three-stage process: (1) a period of preparation during which the therapist explores the patients repertory of life experiences and facilitates constructive frames of reference to orient the patient toward therapeutic change; (2) an activation and utilization of the patient's own mental skills during a period of therapeutic trance; (3) a careful recognition, evaluation, and ratification of the therapeutic change that takes place. In this first chapter we will introduce some of the factors contributing to the successful experience of each of these three stages. In the chapters that follow we will illustrate and discuss them in greater detail.

1. Preparation

The initial phase of hypnotherapeutic work consists of a careful period of observation and preparation. Initially the most important factor in any therapeutic interview is to establish a sound rapport - that is, a positive feeling of understanding and mutual regard between therapist and patient. Through this rapport therapist and patient together create a new therapeutic frame of reference that will serve as the growth medium in which the patient's therapeutic responses will develop. The rapport is the means by which therapist and patient secure each others' attention. Both develop a yes set, or acceptance of each other. The therapist presumably has a well developed ability to observe and relate; the patient is learning to observe and achieve a state of response attentiveness , that state of extreme attentiveness in responding to the nuances of communication presented by the therapist.

In the initial interview the therapist gathers the relevant facts regarding the patient's problems and the repertory of life experiences and learnings that will be utilized for therapeutic purposes. Patients have problems because of learned limitations. They are caught in mental sets, frames of reference, and belief systems that do not permit them to explore and utilize their own abilities to best advantage. Human beings are still in the process of learning to use their potentials. The therapeutic transaction ideally creates a new phenomenal world in which patients can explore their potentials, freed to some extent from their learned limitations. As we shall later see, therapeutic trance is a period during which patients are able to break out of their limited frameworks and belief systems so they can experience other patterns of functioning within themselves. These other patterns are usually response potentials that have been learned from previous life experience but, for one reason or another, remain unavailable to the patient. The therapist can explore patients' personal histories, character, and emotional dynamics, their field of work, interests, hobbies, and so on to assess the range of life experiences and response abilities that may be available for achieving therapeutic goals. Most of the cases in this book will illustrate this process.

As the therapist explores the patient's world and facilitates rapport, it is almost inevitable that new frames of reference and belief systems are created. This usually happens whenever people meet and interact closely. In hypnotherapy this spontaneous opening and shifting of mental frameworks and belief systems is carefully studied, facilitated, and utilized. The therapist is in a constant process of evaluating what limitations are at the source of the patient's problem and what new horizons can be opened to help the patient outgrow those limitations. In the preparatory phase of hypnotherapeutic work mental frameworks are facilitated in a manner that will enable the patient to respond to the suggestions that will be received later during trance. Suggestions made during trance frequently function like keys turning the tumblers of a patient's associative processes within the locks of certain mental frameworks that have already been established. A number of workers (Weitzenhoffer, 1957, Schneck, 1970, 1975) have described how what is said before trance is formally induced can enhance hypnotic suggestion. We agree and emphasize that effective trance work is usually preceded by a preparatory phase during which we help patients create an optimal attitude and belief system for therapeutic responses.

A singularly important aspect of this optimal attitude is expectancy. Patients' expectations of therapeutic change permits them to suspend the learned limitations and negative life experiences that are at the source of their problems. A suspension of disbelief and an extraordinarily high expectation of cure has been used to account for the miraculous healing sometimes achieved within a religious belief system. As will be seen in our overall analysis of the dynamics of therapeutic trance in the following section, such seemingly miraculous healing can be understood as a special manifestation of the more general process we utilize to facilitate therapeutic responses in hypnotherapy.

2. Therapeutic Trance

Therapeutic trance is a period during which the limitations of one's usual frames of reference and beliefs are temporarily altered so one can be receptive to other patterns of association and modes of mental functioning that are conducive to problem-solving. We view the dynamics of trance induction and utilization as a very personal experience wherein the therapist helps patients to find their own individual ways. Trance induction is not a standardized process that can be applied in the same way to everyone. There is no method or technique that always works with everyone or even with the same person on different occasions. Because of this we speak of approaches to trance experience. We thereby emphasize that we have many means of facilitating, guiding, or teaching how one might be led to experience the state of receptivity that we call therapeutic trance. However, we have no universal method for effecting the same uniform trance state in everyone. Most people with problems can be guided to experience their own unique variety of therapeutic trance when they understand that it may be useful. The art of the hypnotherapist is in helping patients reach an understanding that will help them give up some of the limitations of their common everyday world view so that they can achieve a state of receptivity to the new and creative within themselves.

For didactic purposes we have conceptualized the dynamics of trance induction and suggestion as a five-stage process, outlined in Figure 1.

While we may use this paradigm as a convenient framework for analyzing many of the hypnotherapeutic approaches we will illustrate in this volume, it must be understood that the individual manifestations of the process will be just as unique and various as are the natures of the people experiencing it. We will now outline our understanding of these five stages.

Figure 1: A five-stage paradigm of the dynamics of trance induction and suggestion (from Erickson and Rossi, 1976.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 . Fixation of Attention

|

via |

Utilizing the patient's beliefs and behavior for focusing attention on inner realities. |

|

|

|

2. Depotentiating Habitual Frameworks and Belief Systems |

via |

Distraction, shock, surprise, doubt, confusion, dissociation, or any other process that interrupts the patient's habitual frameworks. |

|

|

|

3. Unconscious Search |

via |

Implications, questions, puns, and other indirect forms of hypnotic suggestion. |

|

|

|

4. Unconscious Process |

via |

Activation of personal associations and mental mechanisms by all the above. |

|

|

|

5. Hypnotic Response |

via |

An expression of behavioral potentials that are experienced as taking place autonomously. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fixation of Attention

The fixation of attention has been the classical approach for initiating therapeutic trance, or hypnosis. The therapist would ask the patient to gaze at a spot or candle flame, a bright light, a revolving mirror, the therapist's eyes, gestures, or whatever. As experience accumulated it became evident that the point of fixation could be anything that held the patient's attention. Further, the point of fixation need not be external; it is even more effective to focus attention on the patient's own body and inner experience. Thus approaches such as hand levitation and body relaxation were developed. Encouraging the patient to focus on sensations or internal imagery led attention inward even more effectively. Many of these approaches have become standardized and are well described in reference works on hypnosis (Weitzenhoffer, 1957; Hartland, 1966; Haley, 1967).

The beginner in hypnotherapy may well study these standardized approaches and closely follow some of them to initiate trance in a formalized manner. They are often highly impressive to the patient and very effective in inducing trance. Student therapists will be in error, however, if they attempt to utilize only one approach as the universal method and thereby blind themselves to the unique motivations and manifestations of trance development in each person. The therapist who carefully studies the process of attention in everyday life as well as in the consulting room will soon come to recognize that an interesting story or a fascinating fact or fantasy can fixate attention just as effectively as a formal induction. Anything that fascinates and holds or absorbs a person's attention could be described as hypnotic. We have the concept of the common everyday trance for those periods in everyday life when we are so absorbed or preoccupied with one matter or another that we momentarily lose track of our outer environment.

The most effective means of focusing and fixing attention in clinical practice is to recognize and acknowledge the patient's current experience. When the therapist correctly labels the patient's ongoing hereand-now experience, the patient is usually immediately grateful and open to whatever else the therapist may have to say. Acknowledging the patient's current reality thus opens a yes set for whatever suggestions the therapist may wish to introduce. This is the basis of the utilization approach to trance induction, wherein therapists gain their patients' attention by focusing on their current behavior and experiences (Erickson, 1958,1959). Illustrations of this utilization approach to trance induction will be presented in our third chapter.

Depotentiating Habitual Frameworks and Belief Systems

In our view one of the most useful psychological effects of fixating attention is that it tends to depotentiate patients' habitual mental sets and common everyday frames of reference. Their belief systems are more or less interrupted and suspended for a moment or two. Consciousness has been distracted. During that momentary suspension latent patterns of association and sensory-perceptual experience have an opportunity to assert themselves in a manner that can initiate the altered state of consciousness that has been described as trance or hypnosis.

There are many means of depotentiating habitual frames of reference. Any experience of shock or surprise momentarily fixates attention and interrupts the previous pattern of association. Any experience of the unrealistic, the unusual, or the fantastic provides an opportunity for altered modes of apprehension. The authors have described how confusion, doubt, dissociation, and disequilibrium are all means of depotentiating patients' learned limitations so that they may become open and available for new means of experiencing and learning, which are the essence of therapeutic trance (Erickson, Rossi, and Rossi, 1976). The interruption and suspension of our common everyday belief system has been described by the junior author as a creative moment (Rossi, 1972a):

But what is a creative moment? Such moments have been celebrated as the exciting hunch by scientific workers and inspiration by people in the arts (Barron, 1969). A creative moment occurs when a habitual pattern of association is interrupted; there may be a spontaneous lapse or relaxation of one's habitual associative process; there may be a psychic shock, an overwhelming sensory or emotional experience; a psychedelic drug, a toxic condition or sensory deprivation may serve as the catalyst; yoga, Zen, spiritual and meditative exercises may likewise interrupt our habitual associations and introduce a momentary void in awareness. In that fraction of a second when the habitual contents of awareness are knocked out there is a chance for pure awareness, the pure light of the void (Evans-Wentz, 1960) to shine through. This fraction of a second may be experienced as a mystic state, satori, a peak experience or an altered state of consciousness (Tart, 1969). It may be experienced as a moment of fascination or falling in love when the gap in one's awareness is filled by the new that suddenly intrudes itself.

The creative moment is thus a gap in one's habitual pattern of awareness. Bartlett (1958) has described how the genesis of original thinking can be understood as the filling in of mental gaps. The new that appears in creative moments is thus the basic unit of original thought and insight as well as personality change. Experiencing a creative moment may be the phenomenological correlate of a critical change in the molecular structure of proteins within the brain associated with learning (Gaito, 1972; Rossi, 1973b), or the creation of new cell assemblies and phase sequences (Hebb, 1963).

The relation between psychological shock and creative moments is apparent: a psychic shock interrupts a person's habitual associations so that something new may appear. Ideally psychological shock sets up the conditions for a creative moment when a new insight, attitude, or behavior change may take place in the subject. Erickson (1948) has also described hypnotic trance itself as a special psychological state which effects a similar break in the patient's conscious and habitual associations so that creative learning can take place.

In everyday life one is continually confronted with difficult and puzzling situations that mildly shock and interrupt one's usual way of thinking. Ideally these problem situations will initiate a creative moment of reflection that may provide an opportunity for something new to emerge. Psychological problems develop when people do not permit the naturally changing circumstances of life to interrupt their old and no longer useful patterns of association and experience so that new solutions and attitudes may emerge.

Unconscious Search and Unconscious Process

In everyday life there are many approaches to fixing attention, depotentiating habitual associations, and thereby initiating an unconscious search for a new experience or solution to a problem. In a difficult situation, for example, one may make a joke or use a pun to interrupt and reorganize the situation from a different point of view. One may use allusions or implications to intrude another way of understanding the same situation. Like metaphor and analogy (Jaynes, 1976) these are all means of momentarily arresting attention and requesting a search - essentially a search on an unconscious level - to come up with a new association or frame of reference. These are all opportunities for creative moments in everyday life wherein a necessary reorganization of one's experience takes place.

In therapeutic trance we utilize similar means of initiating a search on an unconscious level. These are what the senior author has described as the indirect forms of suggestion (Erickson and Rossi, 1976; Erickson, Rossi, and Rossi, 1976). In essence, an indirect suggestion initiates an unconscious search and facilitates unconscious processes within patients so that they are usually somewhat surprised by their own responses. The indirect forms of suggestion help patients bypass their learned limitations so they are able to accomplish a lot more than they are usually able to. The indirect forms of suggestion are facilitators of mental associations and unconscious processes. In the next chapter we will outline our current understanding of a variety of these indirect forms of suggestion.

The Hypnotic Response

The hypnotic response is the natural outcome of the unconscious search and processes initiated by the therapist. Because it is mediated primarily by unconscious processes within the patient, the hypnotic response appears to occur automatically or autonomously; it appears to take place all by itself in a manner that may seem alien or dissociated from the person's usual mode of responding on a voluntary level. Most patients typically experience a mild sense of pleasant surprise when they find themselves responding in this automatic and involuntary manner. That sense of surprise, in fact, can generally be taken as an indication of the genuinely autonomous nature of their response.

Hypnotic responses need not be initiated by the therapist, however. Most of the classical hypnotic phenomena, in fact, were discovered quite by accident as natural manifestations of human behavior that occurred spontaneously in trance without any suggestion whatsoever. Classical hypnotic phenomena such as catalepsy, anesthesia, amnesia, hallucinations, age regression, and time distortion are all spontaneous trance phenomena that were a source of amazement and bewilderment to early investigators. It was when they later attempted to induce trance and study trance phenomena systematically that these investigators found that they could suggest the various hypnotic phenomena. Once they found it possible to do this, they began to use suggestibility itself as a criterion of the validity and depth of trance experience.

When the next step was taken to utilize trance experience as a form of therapy, hypnotic suggestibility was emphasized even more as the essential factor for successful work. An unfortunate side effect of this emphasis on suggestibility was in the purported power of hypnotists to control behavior with suggestion. By this time our conception of hypnotic phenomena had moved very far indeed from their original discovery as natural and spontaneous manifestations of the mind. Hypnosis acquired the connotations of manipulation and control. The exploitation of naturally occurring trance phenomena as a demonstration of power, prestige, influence, and control (as it has been used in stage hypnosis) was a most unfortunate turn in the history of hypnosis.

In an effort to correct such misconceptions the senior author (Erickson, 1948) described the merits of direct and indirect suggestion in hypnotherapy as follows:

The next consideration concerns the general role of suggestion in hypnosis. Too often, the unwarranted and unsound assumption is made that, since a trance state is induced and maintained by suggestion, and since hypnotic manifestations can be elicited by suggestion, whatever develops from hypnosis must necessarily and completely be a result and primary expression of suggestion. Contrary to such misconceptions, the hypnotized person remains the same person. Only his behavior is altered by the trance state, but even so, that altered behavior derives from the life experience of the patient and not from the therapist. At the most, the therapist can influence only the manner of self-expression. The induction and maintenance of a trance serve to provide a special psychological state in which the patient can reassociate and reorganize his inner psychological complexities and utilize his own capacities in a manner concordant with his own experiential life. Hypnosis does not change the person, nor does it alter his past experiential life. It serves to permit him to learn more about himself and to express himself more adequately.

Direct suggestion is based primarily, if unwittingly, upon the assumption that whatever develops in hypnosis derives from the suggestions given. It implies that the therapist has the miraculous power of effecting therapeutic changes in the patient, and disregards the fact that therapy results from an inner resynthesis of the patient's behavior achieved by the patient himself. It is true that direct suggestion can effect an alteration in the patient's behavior and result in a symptomatic cure, at least temporarily. However, such a cure is simply a response to the suggestion and does not entail that reassociation and reorganization of ideas, understandings and memories so essential for an actual cure. It is this experience of reassociating and reorganizing his own experiential life that eventuates in a cure, not the manifestation of responsive behavior which can, at best, satisfy only the observer.

For example, anesthesia of the hand may be suggested directly and a seemingly adequate response may be elicited. However, if the patient has not spontaneously interpreted the command to include a realization of the need for inner reorganization, that anesthesia will fail to meet clinical tests and will be a pseudo-anesthesia.

An effective anesthesia is better induced, for example, by initiating a train of mental activity within the patient himself by suggesting that he recall the feeling of numbness experienced after a local anesthetic, or after a leg or arm went to sleep, and then suggesting that he can now experience a similar feeling in his hand. By such an indirect suggestion the patient is enabled to go through those difficult inner processes of disorganizing, reorganizing, reassociating and projecting inner real experience to meet the requirements of the suggestion. Thus, the induced anesthesia becomes a part of his experiential life, instead of a simple, superficial response.

The same principles hold true in psychotherapy. The chronic alcoholic can be induced by direct suggestion to correct his habits temporarily, but not until he goes through the inner process of reassociating and reorganizing his experiential life can effective results occur.

In other words, hypnotic psychotherapy is a learning process for the patient, a procedure of reeducation. Effective results in hypnotic psychotherapy, or hypnotherapy, derive only from the patient's activities. The therapist merely stimulates the patient into activity, often not knowing what that activity may be, and then he guides the patient and exercises clinical judgment in determining the amount of work to be done to achieve the desired results. How to guide and to judge constitute the therapist's problem while the patient's task is that of learning through his own efforts to understand his experiential life in a new way. Such reeducation is, of course, necessarily in terms of the patient's life experiences, his understandings, memories, attitudes and ideas, and it cannot be in terms of the therapist's ideas and opinions.

In our work, therefore, we prefer to emphasize how therapeutic trance helps people sidestep their own learned limitations so that they can more fully explore and utilize their potentials. The hypnotherapist makes many approaches to altered states of functioning available to the patient. Most patients really cannot direct themselves consciously in trance experience because such direction can come only from their previously learned habits of functioning which are inhibiting the full utilization of their potentials. Patients must therefore learn to allow their own unconscious response potentials to become manifest during trance. The therapist, too, must depend upon the patient's unconscious as a source of creativity for problem-solving. The therapist helps the patient find access to this creativity via that altered state we call therapeutic trance. Therapeutic trance can thus be understood as a free period of psychological exploration wherein therapist and patient cooperate in the search for those hypnotic responses that will lead to therapeutic change. We will now turn our attention to the evaluation and facilitation of that change.

3. Ratification of Therapeutic Change

The recognition and evaluation of altered patterns of functioning facilitated by therapeutic trance is one of the most subtle and important tasks of the therapist. Many patients readily recognize and admit changes that they have experienced. Others with less introspective ability need the therapist's help in evaluating the changes that have taken place. A recognition and appreciation of the trance work is necessary, lest the patient's old negative attitudes disrupt and destroy the new therapeutic responses that are still in a fragile state of development.

The Recognition and Ratification of Trance

Different individuals experience trance in different ways. The therapist's task is to recognize these individual patterns and when necessary point them out to patients to help verify or ratify their altered state of trance. Consciousness does not always recognize its own altered states. How often do we not recognize that we are actually dreaming? It is usually only after the fact that we recognize we were in a state of reverie or daydreaming. The inexperienced user of alcohol and psychedelic drugs must also learn to recognize and then go with the altered state in order to enhance and fully experience its effects. Since therapeutic trance is actually only a variation of the common everyday trance or reverie that everyone is familiar with but does not necessarily recognize as an altered state, some patients will not believe they have been affected in any way. For these patients, in particular, it is important to ratify trance as an altered state. Without this proof the patient's negative attitudes and beliefs can frequently undo the value of the hypnotic suggestion and abort the therapeutic process that has been initiated.

Because of this we will list in Table 1 some of the common indicators of trance experience which we have previously discussed and illustrated in some detail (Erickson, Rossi, and Rossi, 1976). Because trance experience is highly individualized, patients will manifest these indicators in varying combinations as well as in different degrees.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 1 |

|

|

|

|

SOME COMMON INDICATORS OF TRANCE EXPERIENCE |

|

|

|

|

Autonomous Ideation and Inner |

Respiration |

|

|

|

Experience |

Swallowing |

|

|

|

|

Startle reflex |

|

|

|

Balanced Tonicity (Catalepsy) |

|

|

|

|

Body Immobility |

Objective and Impersonal Ideation |

|

|

|

Body Reorientation After Trance |

Psychosomatic Responses |

|

|

|

Changed Voice Quality |

Pupillary Changes |

|

|

|

Comfort, Relaxation |

Response Attentiveness |

|

|

|

Economy of Movement |

Sensory, Muscular Body Changes |

|

|

|

|

(Paresthesias) |

|

|

|

Expectancy |

|

|

|

|

|

Slowing Pulse |

|

|

|

Eye Changes and Closure |

|

|

|

|

|

Spontaneous Hypnotic Phenomena |

|

|

|

Facial Features Smooth Relaxed |

Amnesia |

|

|

|

|

Anesthesia |

|

|

|

Feeling Distanced or Dissociated |

Body Illusions |

|

|

|

|

Catalepsy |

|

|

|

Feeling Good After Trance |

Regression |

|

|

|

|

Time Distortion |

|

|

|

Literalism |

etc. |

|

|

|

Loss or Retardation of Reflexes |

Time Lag in Motor and Conceptual |

|

|

|

Blinking |

Behavior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most of these indicators will be illustrated as they appear in the cases of this book.

We look upon the spontaneous development of hypnotic phenomena such as age regression, anesthesia, catalepsy, and so on as more genuine indicators of trance than when these same phenomena are suggested. When they are directly suggested, we run into the difficulties imposed by the patient's conscious attitudes and belief system. When they come about spontaneously, they are the natural result of the dissociation or reorganization of the patient's usual frames of reference and general reality orientation which is characteristic of trance.

Certain investigators have selected some of these spontaneous phenomena as defining characteristics of the fundamental nature of trance. Meares (1957) and Shor (1959), for example, have taken regression as a fundamental aspect of trance. From our point of view, however, regression per se is not a fundamental characteristic of trance, although it is often present as an epiphenomenon of the early stage of trance development, when patients are learning to give up their usual frames of reference and modes of functioning. In this first stage of learning to experience an altered state, many uncontrolled things happen, including spontaneous age regression, paresthesias, anesthesias, illusions of body distortion, psychosomatic responses, time distortion, and so on. Once patients learn to stablize these unwanted side reactions, they can then allow their unconscious minds to function freely in interacting with the therapist's suggestions without some of the limitations of their usual frames of reference.

Ideomotor and Ideosensory Signaling

Since much hypnotherapeutic work does not require a dramatic experience of classical hypnotic phenomena, it is even more important that the therapist learn to recognize the minimal manifestations of trance as alterations in a patient's sensory-perceptual, emotional, and cognitive functioning. A valuable means of evaluating these changes is in the use of ideomotor and ideosensory signaling (Erickson, 1961; Cheek and Le Cron, 1968). An experience of trance as an altered state can be ratified by requesting any one of a variety of ideomotor responses as follows:

If you have experienced some moments of trance in our work today, your right hand (or one of your fingers) can lift all by itself.

If you have been in trance today without even realizing it, your head will nod yes (or your eyes will close) all by itself.

The existence of a therapeutic change can be signaled in a similar manner.

If your unconscious no longer needs to have you experience (whatever symptom), your head will nod.

Your unconscious can review the reasons for that problem, and when it has given your conscious mind its source in a manner that is comfortable for you to discuss, your right index finger can lift all by itself.

Some subjects experience ideosensory responses more easily than other subjects. They may thus experience a feeling of lightness, heaviness, coolness, or prickliness in the designated part of the body.

In requesting such responses we are presumably allowing the patient's unconscious to respond in a manner that is experienced as involuntary by the patient. This involuntary or autonomous aspect of the movement or feeling is an indication that it comes from a response system that is somewhat dissociated from the patient's habitual pattern of voluntary or intentional response. The patient and therapist thus have indication that something has happened independently of the patient's conscious will. That something may be trance or whatever therapeutic response was desired.

An uncritical view of ideomotor and ideosensory signaling takes such responses to be the true voice of the unconscious. At this stage of our understanding we prefer to view them as only another response system that must be checked and crossed-validated just as any other verbal or nonverbal response system. We prefer to evoke ideomotor responses in such a manner that the patient's conscious mind may not witness them (for example, having eyes closed or averted when a finger or hand signal is given). It is very difficult, however, to establish that the conscious mind is unaware of what response is given and that the response is in fact given independently of conscious intention. Some patients feel that the ideomotor or ideosensory response is entirely on an involuntary level. Others feel they must help it or at least know ahead of time what it is to be.

A second major use of ideomotor and ideosensory signaling is to help patients restructure their belief system. Doubts about therapeutic change may persist even after an extended period of exploring and dealing with a problem in trance. These doubts can often be relieved when the patient believes in ideomotor or ideosensory responses as an independent index of the validity of therapeutic work. The therapist may proceed, for example, with suggestions as follows:

If your unconscious acknowledges that a process of therapeutic change has been initiated, your head can nod.

When you know you need no longer be bothered by that problem, your index finger can lift, or get warm [or whatever].

In such usage there is value, of course, in having the patient's conscious mind recognize the positive response. The more autonomous or involuntary the ideomotor or ideosensory response, the more convincing it is to the patient.

At the present time we have no way of distinguishing when an ideomotor or ideosensory response is (1) a reliable and valid index of something happening in the unconscious (out of the patient's immediate range of awareness), or (2) simply a means of restructuring a conscious belief system. A great deal of carefully controlled experimental work needs to be done in this area. It is still a matter of clinical judgment to determine which process, or the degree to which both processes, are operating in any individual situation.

Summary

Our utilization approach to hypnotherapy emphasizes that therapeutic trance is a means by which we help patients learn to use their mental skills and potentials to achieve their own therapeutic goals. While our approach is patient-centered and highly dependent on the momentary needs of the individual, there are three basic phases that can be outlined and discussed for didactic purposes: Preparation, Therapeutic Trance, and Ratification of Therapeutic Change.

The goal of the initial preparatory period is to establish an optimal frame of reference to orient the patient toward therapeutic change. This is facilitated by the following factors, which were discussed in this chapter and which will be illustrated in the cases of this book.

Rapport

Response Attentiveness

Assessing Abilities to Be Utilized

Facilitating Therapeutic Frames of Reference

Creating Expectancy

Therapeutic trance is a period during which the limitations of one's habitual frames of reference are temporarily altered so that one can be receptive to more adequate modes of functioning. While the experience of trance is highly variable, the overall dynamics of therapeutic trance and suggestion could be outlined as a five-stage process: (1) Fixation of attention; (2) depotentiating habitual frameworks; (3) unconscious search; (4) unconscious processes; (5) therapeutic response.

The utilization approach and the indirect forms of suggestion are the two major means of facilitating these overall dynamics of therapeutic trance and suggestion. The utilization approach emphasizes the continual involvement of each patient's unique repertory of abilities and potentials, while the indirect forms of suggestion are the means by which the therapist facilitates these involvements.

We believe that the induction and maintenance of therapeutic trance provides a special psychological state in which patients can reassociate and reorganize their inner experience so that therapy results from an inner resynthesis of their own behavior.

Ratifying the process of therapeutic change is an integral part of our approach to hypnotherapy. This frequently involves a special effort to help patients recognize and validate their altered state. The therapist must develop special skills in learning to recognize minimal manifestations of altered functioning in sensory-perceptual, emotional, and cognitive processes. Ideomotor and ideosensory signaling are of special use as an index of therapeutic change as well as a means of facilitating an alteration of the patient's belief system.

Exercises

1. New observational skills are the first stage in the training of the hypnotherapist. One needs to learn to recognize the momentary variations in another's mentation. These skills can be developed by training oneself to carefully observe the mental states of people in everyday life as well as in the consulting room. There are at least four levels, ranging from the most obvious to the more subtle.

1. Role relations

2. Frames of reference

3. Common everyday trance behaviors

4. Response attentiveness

1. Role relations: Carefully note the degree to which individuals in all walks of life are caught within roles, and the degrees of flexibility they have in breaking out of their roles to relate to you as a unique person. For example, to what degree are the clerks at the supermarket identified with their roles? Notice the nuances of voice and body posture that indicate their role behavior. Does their tone and manner imply that they think of themselves as an authority to manipulate you, or are they seeking to find out something about you and what you really need? Explore the same questions with police, officials of all sorts, nurses, bus drivers, teachers, etc.

2. Frames of reference: To the above study of 'role relations add an inquiry into the dominant frames of reference that are guiding your subject's behavior. Is the bus or taxicab driver more dominated by a safety fame of reference? Which of the store clerks is more concerned with securing his present job and which is obviously bucking for a promotion? Is the doctor more obviously operating within a financial or therapeutic frame of reference?

3. Common everyday trance behavior: Table 1 can be a guide as to what to look for in evaluating a person's everyday trance behavior. Even in ordinary conversation one can take careful note of those momentary pauses when the other person is quietly looking off into the distance or staring at something, as he or she apparently reflects inward. One can ignore and actually ruin these precious moments when the other is engaged in inner search and unconscious processes by talking too much and thereby distracting the person. How much better simply to remain quiet oneself and carefully observe the individual manifestations of the other's everyday trance behavior. Notice especially whether the person's eye blink slows down or stops altogether. Do the eyes actually close for a moment? Does the body not remain perfectly immobile, perhaps even with limbs apparently cataleptic, fixed in mid-gesture?

Watching for these moments and pauses is especially important in psychotherapy. The authors will themselves sometimes freeze in mid-sentence when they observe the patient going off into such inward focus. We feel what we are saying is probably less important than allowing the patient to have that inward moment. Sometimes we can facilitate the inner search by simply saying things such as:

That's right, continue just as you are.

Follow that now.

Interesting isn't it?

Perhaps you can tell me some of that later.

After a while patients become accustomed to this unusual tolerance and reinforcement of their inner moments; the pauses grow longer and become what we would call therapeutic trance. The patients then experience increasing relaxation and comfort and may prefer to respond with ideomotor signals as they give increasing recognition to their trance state.

4. Response Attentiveness: This is the most interesting and useful of the trance indicators. The junior author can recall that lucky day when a series of three patients seen individually on successive hours just happened to manifest a similar wide-eyed look of expectancy, staring fixedly into his eyes. They also had a similar funny little smile (or giggle) of wistfulness and mild confusion. That was it! Suddenly he recognized what the senior author had been trying to teach him for the past five years: Response attentiveness! The patients may not have realized themselves just how much they were looking to the junior author for direction at that moment. That was the moment to introduce a therapeutic suggestion or frame of reference! That was the moment to introduce trance either directly or indirectly! The junior author can recall the same slight feeling of discomfort with each patient at that moment. The patient's naked look of expectancy bespoke a kind of openness and vulnerability that is surprising and a bit disconcerting when it is suddenly encountered. In everyday situations we tend to look away and distract ourselves from such delicate moments. At most we allow ourselves to enjoy them briefly with children or during loving encounters. In therapy such creative moments are the precious openers of the yes set and positive transference. Hypnotherapists allow themselves to be open to these moments and perhaps to be equally vulnerable as they offer some tentative therapeutic suggestions. More detailed exercises on the recognition and utilization of response attentiveness will be presented at the end of Chapter Three.

CHAPTER 2

The Indirect Forms of Suggestion

1. Direct and Indirect Suggestion

A direct suggestion makes an appeal to the conscious mind and succeeds in initiating behavior when we are in agreement with the suggestion and have the capacity actually to carry it out in a voluntary manner. If someone suggests, Please close the window, I will close it if I have the physical capacity to do so, and if I agree that it's a good suggestion. If the conscious mind had a similar capacity to carry out all manner of psychological suggestions in an agreeable and voluntary manner, then psychotherapy would be a simple matter indeed. The therapist would need only suggest that the patient give up such and such a phobia or unhappiness and that would be the end of the matter.

Obviously this does not happen. Psychological problems exist precisely because the conscious mind does not know how to initiate psychological experience and behavior change to the degree that one would like. In many such situations there is some capacity for desired patterns of behavior, but they can only be carried out with the help of an unconscious process that takes place on an involuntary level. We can make a conscious effort to remember a forgotten name, for example, but if we cannot do so, we cease trying after a few moments of futile effort. Five minutes later the name may pop up spontaneously within our minds. What has happened? Obviously a search was initiated on a conscious level, but it could only be completed by an unconscious process that continued on its own even after consciousness abandoned its effort. Sternberg (1975) has reviewed experimental data supporting the view that an unconscious search continues at the rate of approximately thirty items per second even after the conscious mind has gone on to other matters.

The indirect forms of suggestion are approaches to initiating and facilitating such searches on an unconscious level. When it is found that consciousness is unable to carry out a direct suggestion, we may then make a therapeutic effort to initiate an unconscious search for a solution by indirect suggestion. The naive view of direct suggestion which emphasizes control maintains that the patient passively does whatever the therapist asks. In our use of indirect suggestion, however, we realize that suggested behavior is actually a subjective response synthesized within the patient. It is a subjective response that utilizes the patient's unique repertory of life experiences and learning. It is not what the therapist says but what the patient does with what is said that is the essence of suggestion. In hypnotherapy the words of the therapist evoke a complex series of internal responses within the patient; these internal responses are the basis of suggestion. Indirect suggestion does not tell the patient what to do; rather, it explores and facilitates what the patient's response system can do on an autonomous level without really making a conscious effort to direct itself.

The indirect forms of suggestion are semantic environments that facilitate the experience of new response possibilities. They automatically evoke unconscious searches and processes within us independent of our conscious will.

In this chapter we shall discuss a number of indirect forms of suggestion that have been found to be of practical value in facilitating hypnotic responsiveness. Most of these indirect forms are in common usage in everyday life. Indeed, this is where the senior author usually recognized their value as he sought more effective means of facilitating hypnotic work.

Because we have already discussed most of these indirect forms from a theoretical point of view (Erickson and Rossi, 1976; Erickson, Rossi, and Rossi, 1976), our emphasis in this chapter will be on their therapeutic applications. It will be seen that many of these indirect forms are closely related to each other, that several can be used in the same phrase or sentence, and that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish one from another. Because of this, it may be of value for the reader to recognize that an attitude or approach is being presented with this material rather than a'' technique'' that is designed to achieve definite and predictable (though limited) results. The indirect forms of suggestion are most useful for exploring potentialities and facilitating a patient's natural response tendencies rather than imposing control over behavior.

2. The Interspersal Approach

The senior author has described the interspersal approach (Erickson, 1966; Erickson and Rossi, 1976) along with nonrepetition as his most important contributions to the practice of suggestion [In a conversation with Anisley Mears, Gordon Ambrose, and others on the evening when the senior author, at the age of seventy-four, was awarded the Benjamin Franklin gold medal for his innovative contributions to hypnosis at the 7th International Congress of Hypnosis on July 2, 1976.]. In the older, more traditional forms of direct suggestion the hypnotherapist usually droned on and on, repeating the same suggestion over and over. The effort was seemingly directed to programming or deeply imprinting the mind with one fixed idea. With the advent of modern psychodynamic psychology, however, we recognize that the mind is in a continual state of growth and change; creative behavior is in a continual process of development. While direct programming can obviously influence behavior (e.g., Coueism, advertising), it does not help us explore and facilitate a patient's unique potentials. The interspersal approach, on the other hand, is a suitable means of presenting suggestions in a manner that enables the patient's own unconscious to utilize them in its own unique way.

The interspersal approach can operate on many levels. We can within a single sentence intersperse a single word that facilitates the patient's associations:

You can describe those feelings as freely as you wish.

The interspersed word freely automatically associates a positive valence of freedom with feelings patients may have suppressed. It can thereby help patients to free feelings that they really want to reveal. Each patient's individuality is still respected, however, because free choice is admitted. The senior author (Erickson, 1966) has illustrated how an entire therapeutic session can be conducted by interspersing words and concepts suggestive of comfort, utilizing the patient's own frames of reference so that pain relief is achieved without the formal induction of trance. Case 1 of this volume will give another clear illustration of this approach. In the following sections we will discuss and illustrate indirect associative focusing and indirect ideodynamic focusing as two aspects of the interspersal approach.

2a. Indirect Associative Focusing

A basic form of indirect suggestion is to raise a relevant topic without directing it in any obvious manner to the patient. The senior author likes to point out that the easiest way to help patients talk about their mothers is to talk about your own mother or mothers in general. A natural indirect associative process is thereby set in motion within patients that brings up apparently spontaneous associations about their mothers. Since we do not directly ask about a patient's mother, the usual limitations of conscious sets and habitual mental frameworks (including psychological defenses) that such a direct question might evoke are bypassed. Bandler and Grinder (1975) have described this process as a transderivational phenomenon - a basic linguistic process whereby subject and object are automatically interchanged at a deep, (unconscious), structural level.