In Search of Hard Evidence:

Ancient Stone Maps

By Bill and Marilyn Kreisle

All figures and symbols at bottom of Page

4-24-95

Note from Host: This amazingly brilliant presentation was introduced at the Spring 1995 ISAC Convention. Soon after, it was published in both the Ancient American and The Midwestern Epigraphic Journal. The information presented is absolutely incredible. This is the very best research paper done on the artifacts from the Lost Tomb before we went public, and it concerns 2 stone maps crafted upon 2 separate tablets.

What Mr. Kreisle unequivocally demonstrates, is extreme professional ability as a Geologist, Cartographer and Natural Historian far beyond the norm. He is a retired military officer of the Army Corps of Engineers after 30 years service. The man is a genius! His presentation is assisted with the aid of his charming wife Marilyn and together they weave a thread that proves the 2 maps stones from the Lost Tomb are genuine. He proves this using information that has only recently surfaced using satellite photos from space.

Ancient Stone Maps

When my wife entered my name on the membership rolls of the Midwest Epigraphic Society, I was definitely an agnostic when it came to such matters as allegedly prehistoric inscriptions in America. But after several trips to Kentucky's Red River Gorge, where I saw such inscriptions etched into sandstone walls by ancient visitors, and after considerable research into the early history of navigation and cartography, I became less skeptical. More recently, I examined some artifacts from Burrows' Cave, in particular, two pocket-sized stones, each of which have carved into their surfaces maps of a river system with major tributaries. Both maps, although differing slightly, appear to depict the Mississippi River Valley. After studying and comparing them to the early history of the Mississippi River and its tributaries, I became convinced and now believe both must be 2000 years old or older.

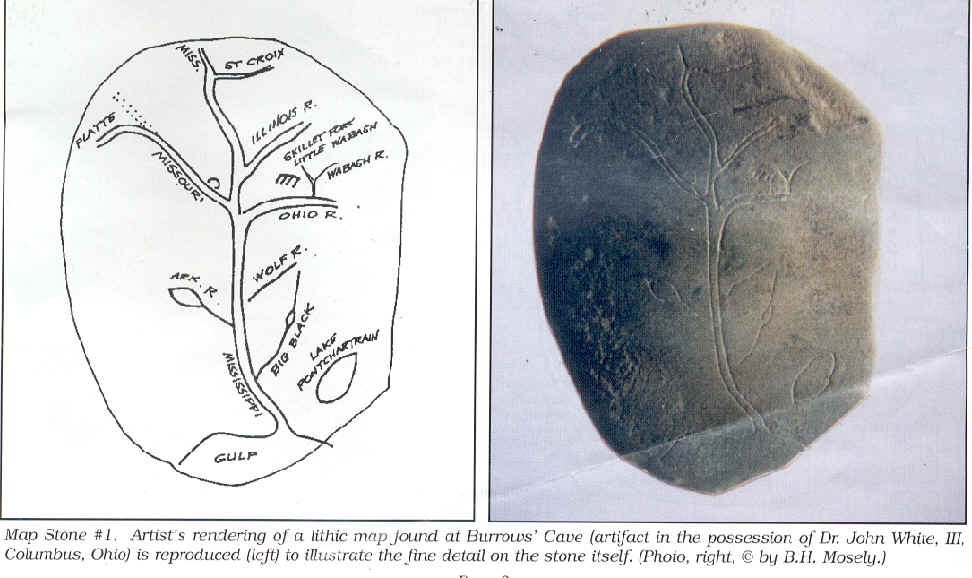

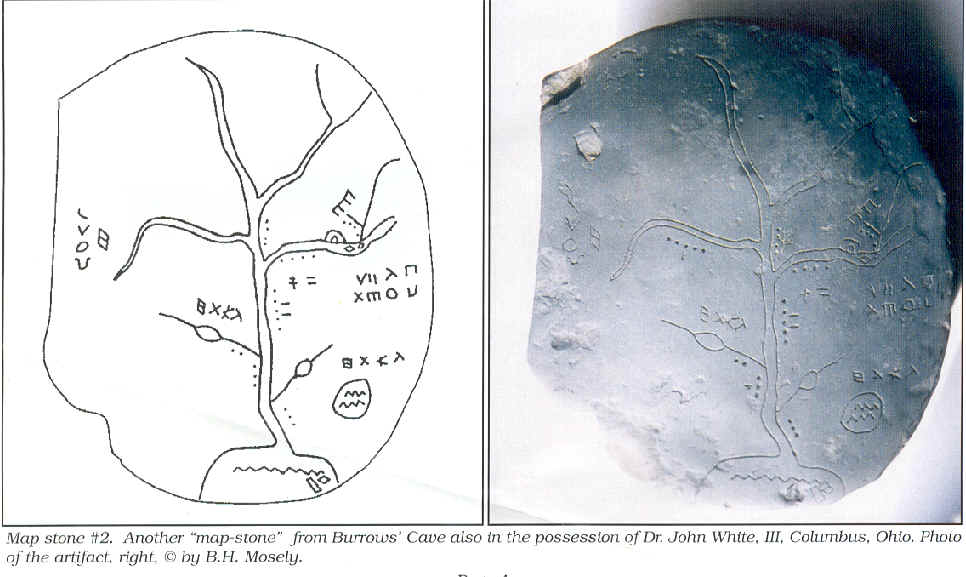

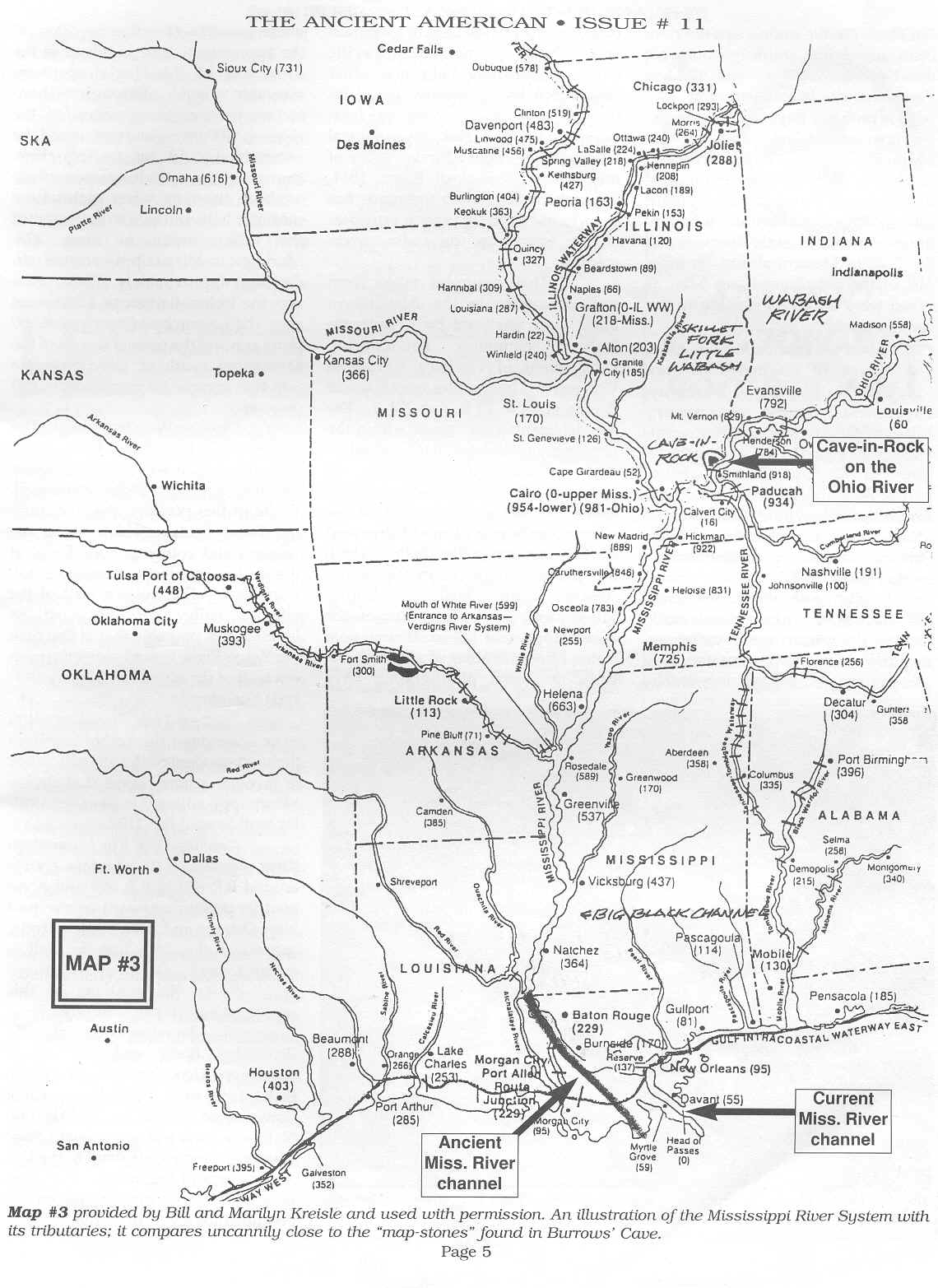

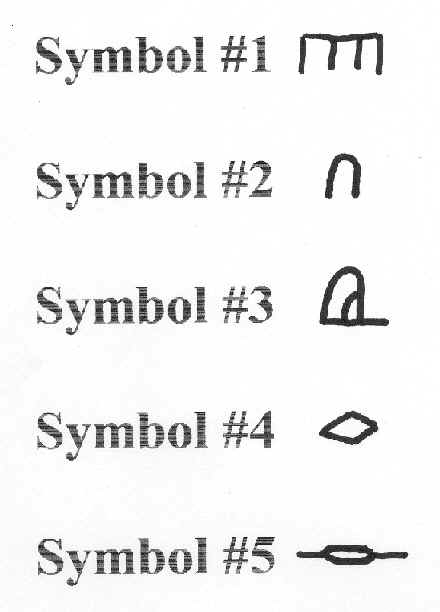

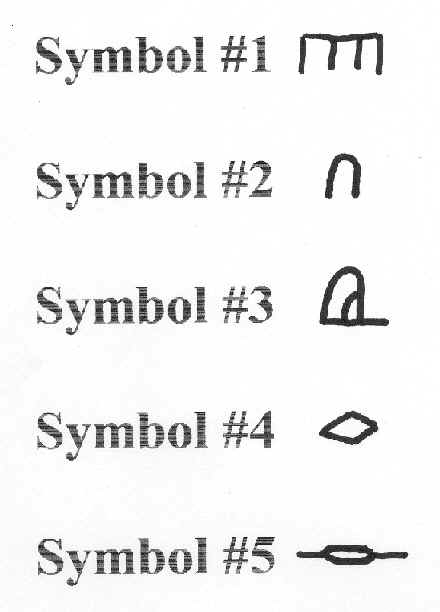

These "mapstones" are similar in size, approximately 3.5 by 4.5 inches, weigh about 6 ounces, and could be carried easily in a knapsack. The two small maps cover the same territory and include the same major Tributaries: The lower Ohio, Illinois, Missouri (Platte), Arkansas, White, and the Yazoo or the Big Black River. The Wabash is also shown with what appears to be Skillet Fork -- a continuation of the Little Wabash in central Illinois. On the West bank of Skillet Fork, Near Burrows Cave, both maps feature a symbol (see Symbol #1) which may indicate a settlement.

Although the stone maps are similar in most respects, there are important differences. Map 1 extends farther north than Map 2, probably beyond Wisconsin's St. Croix River. map 2 shows the southern tip of Lake Michigan, perhaps indicating that the creators of the maps came from the south and were, therefore, not Norsemen. Map 1 also shows a horse-shoe-like symbol (see Symbol #2) near the mouth of the Missouri River, in the vicinity of an abandoned Mandan village mentioned in William Clark's account of his journeys to the Pacific Ocean. This map also shows the Missouri River (dotted) extending past the Platte River in Nebraska. Note that Map 1 shows a slightly different course where the Mississippi flows into the Gulf. This subtle change could mean a difference of 500 years in age. (see Map 3).

Map 2 features many other, indecipherable symbols. We may venture an interpretation of some because of their shapes and relative positions on the stone. A symbol (see Symbol #3) lies in the exact location of the Ohio River where Illinois' Cave-In-Rock is found. Interestingly, this site, only 85 miles miles from Burrows Cave, was said by early settlers to contain "Egyptian-like" artifacts.

In 1833, Josiah Priest, an early explorer of the area, wrote, "On the Ohio, twenty miles below the mouth of the Wabash, is a cavern, in which are found many hieroglyphics, and representations of such delineations as would induce the belief that their authors were, indeed, comparatively refined and civilized."2 He goes on to describe the size and shape of the cave and how it may have been used in prehistoric times. He further describes paintings of animals and humans, plants and heavenly bodies that decorated the walls of this remarkable cave. Although many of the paintings were faded, most could still be seen. Priest wrote that the apparel worn by the human figures depicted on the cave walls seemed similar to Old World dress worn during some Greco-Roman era.3

In 1848, another early traveler, William Pidgeon, published his findings regarding Cave-In-Rock and its unusual paintings. He described its anthropomorphic pictographs which he believed represented ancient Egyptians. The figures appeared to portray multi-racial groups, the result, he concluded, of countless pre-Columbian voyages from various parts of the world. Sadly, a recent visit to the cave by members of the Midwest Epigraphic Society revealed not a spec of paint, nor a hint of its former mystery. Over 150 years of abuse, flooding, and public fascination with its history of crime during the nineteenth Century have left its floors muddy and its walls scarred with 20th Century graffiti. Sometime during its last one hundred years, an upper cavern directly over the main cave collapsed, leaving a large hole in the roof and depositing rock and clay over the floor.

Returning to the Burrows Cave artifact, among its many symbols, one (see Symbol #4) is clearly identifiable: It appears to represent the Ohio River where Saline River towhead, once a very large island, is presently located. The same symbol recurs at the mouth of the Wabash River where Wabash Island is found today.5

On map 2, dots along the banks may indicate the number of days it took to travel between designated landmarks. The number of dots between these known positions are roughly proportional to the river miles between them (see Map 3). The symbol (see Symbol #5) seen on both the Arkansas and Big Black Rivers may indicate very large bayous, although the Arkansas River symbol could also indicate the White River juncture.

In 1819, Thomas Nuttall, an explorer and botanist who later became a member of the American Philosophical Society, traveled by flat-boat down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers for the purpose of studying the Arkansas Territory. On the Ohio, he documented many mounds and village sites, including a mound at eh mouth of Little Grave Creek, West Virginia. It was 75 feet high and looked to him "indeed like a very large pyramid." Unfortunately, he passed what he called "Rock-in-the-Cave" at night. "Here I was advised to proceed with my small cargo and flat-boat to the port of Osark, on the Arkansas by the bayou, which communicates between the White and Arkansas Rivers."6 According to Nuttall, the bayou extended for many miles between the two rivers.

On Maps 1 and 2 the same symbol (see Symbol #5) appears on both the Big Black and the Arkansas Rivers. A satellite image of the Big Black River east of Vicksburg, Mississippi, reveals a circular configuration similar to the symbol on the map. Except by satellite imagery or aerial photography, it would not be known.

In studying the courses of the Mississippi River on the map-stones and comparing them to the present day channel, it is apparent that a noticeable change has occurred on the lower river past the mouth of the Big Black. On the stone maps the river continues in a south-by-southeast direction, staying far west of Lake Pontchartrain before running into what is probably Bayou Lafourche, the old river channel. Today, the river runs southeast past Baton Rouge, Louisiana, turning almost due east until it passes by near the southern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, then continues in a southeasterly direction into the Gulf of Mexico, almost 50 miles east of the old channel (see Map #3) When were the rivers running in this configuration?

To find the answer, I turned to the Corps of Engineers in New Orleans and to the Waterways Experimental Station in Vicksburg, Mississippi. The following excerpts were taken from the report, Mississippi River and Tributaries Old River Control, part of Memorandum No. 17-Hydraulic Design, furnished by Arthur Laurent, Chief of the Hydraulics Branch, New Orleans District Corps of Engineers: Section II-2 d:

"Dating the Entrenched Valley and Alluvium. The time estimates used to show the general age of valley cutting and valley filling, are taken from accepted Quaternary chronology base on worldwide belts of glaciation and related phenomena. Specific dation of meander belts and other Mississippi Valley features based on the rate of meander growth has been developed by Fisk, Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River, 1944. Support for this dating technique has been found in more precise estimates of age based on the radio-carbon method.

"Three samples taken from various depths in the Atchafalaya Basin were analyzed by J. Laurence Kulp, Lamont Laboratories, Department of Geology, Columbia University. The samples were taken at depths of 25ft, 73 ft, and 273 ft. The age determinations agreed within the previously established geologic dates.

"Section III-8. Dating the Courses. Each of the Mississippi River courses in the southern part of the alluvial valley is marked by well developed meander belts which merge into a single belt extending upstream from near Vicksburg, Mississippi, to the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers near Cairo, Illinois. Studies of accretion features on aerial photography have made possible the determination of the approximate time involved in the formation of the single upstream meander belt. Through those reconstructions, the position of the river at 100-year intervals could be ascertained, and by tracing these courses downstream it was possible to establish the time when each of the meander belts in the southern part of the valley began to form. The Maringouin-Mississippi started to develop approximately 3,000 years ago; the Teche-Mississippi, 2,000 years ago; the Lafourche-Mississippi, 1,600 years ago and the present course of the Mississippi south of Donaldsonville was fist occupied approximately 8-- years ago.

"Section IV-3. Teche Stage. The earliest of the Mississippi River courses in this region which may be easily traced is that of the Teche-Mississippi. While in this position, the river built the Teche Bridge, which forms the western and southern boundaries of the basin. The Teche-Mississippi follows closely the western wall of the alluvial valley for much of its length....It is probable that at this time the Yazoo River flowed along the eastern wall of the Mississippi Valley, (B.P. 1900. See Map 3).

"Section IV-4. The Mississippi River abandoned the Teche course on the western shed of the alluvial valley in favor or a new course (Lafourche-Mississippi) adjacent to its eastern valley wall around B.P. 1100.

"Section IV-5. The Mississippi River abandoned its lafourche course around B.P. 800 to 600 and occupied its present eastward course past New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain, turning southeasterly into the Gulf as it does today."

Note: the contents of this report were taken largely from Geological Investigation of the Atchafalay Basin and problem of Mississippi River Diversion, by Harold Fisk for the Mississippi River Commission, (1952). In 1944, Harold N. Fisk, a professor at Louisiana State University and a consultant to the U.S. Army corps of Engineers, wrote what became a classic monograph on the geomorphology of the lower Mississippi Valley. For the next 30 or more years it was considered the authoritative reference on the geologic history and chronology of this area. This classic was followed in 1952 by another study for the Mississippi River Commission. In these studies, Fisk developed a chronology for specific dating of meander belts and other Mississippi Valley features based on the rate of meander growth. These studies would indicate that the Mississippi turned east sometime between B.P. 1900 and 1100.8

During the past 30 years, however, another generation of scientists, using new tools and new techniques, have taken a closer look at Fisk's work and found it to be lacking.9 Much of this latter work has been done on an interdisciplinary basis, which includes not only geologists, but also archaeologists, engineers, biologists, etc. One of the leaders of this movement has been Roger T. Saucier of the U.S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station at Vicksburg. It has been authoritatively established that Fisk underestimated the time of some geologic events by as much as several thousand years.

This, of course, has given us a new approximation for the date when the Mississippi River turned eastward and no longer follows the rough courses shown on the stone maps. In discussion of this problem, Mr. Saucier estimated the eastern course of the lower Mississippi to be approximately 2000 years old or older. Such would, in the author's opinion, date these maps to 2500 years ago.

This rather esoteric knowledge regarding the eastward turn of the lower Mississippi from its original southeasterly direction as depicted on the map-stones would hardly be widely dispersed today, thus minimizing possibilities of anyone manufacturing bogus artifacts. If anything, the appearance of clearly recognizable river systems in the Midwest generally and Illinois specifically, as the stones indicate, go a long way toward establishing the discoveries in Burrows' Cave as genuine.

Refer to the above figure when used within the text.