|

|

The following text is based on a paper delivered in November 2009 at the memorial site House of the Wannsee Conference in Berlin, Germany. A longer German version is available here. An even more detailed German-language article with complete references can be downloaded here. In addition, the memorial site's multi-language webpage at www.ghwk.de offers a wealth of material, including scans of historical documents. For generous and invaluable assistance in translating the text and beyond, the author wishes to thank Gord McFee.

For Harry Mazal, as promised

The Wannsee Protocol: Object of Revisionist Falsification of History

by Christian Mentel

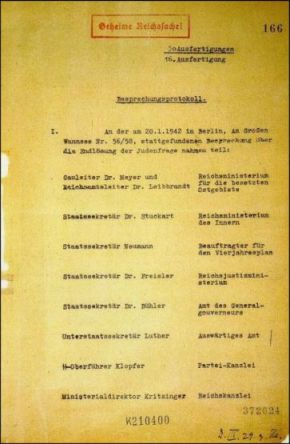

The Wannsee Conference - which was initially scheduled for December 9, 1941 but postponed on short notice - took place on January 20, 1942 at a suburban villa on the shores of Berlin's Wannsee lake. Chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt), 15 high-ranking officials of the German bureaucracy, the SS- and police-apparatus discussed the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question", while enjoying the lovely sight of the villa's gardens and the lake. It was only after the Protocol (minutes) of the conference was found in 1947 that the conference was named "Wannsee Conference" after its location.

The Wannsee Conference and Protocol

According to most historians of the Holocaust, the purpose of the conference was to coordinate and make more effective the mass murder operations under the leadership of Heydrich, moreover to solve problems like internal fights over mandates. The mass murder of Jews in the East was well underway since Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, but was nevertheless poorly coordinated. The leadership of the SS, and in particular the Reich Security Main Office in these murder operations (which from now on were to be understood as part of the attempt to murder all European Jews), was accepted by the participants at the conference, although disagreements remained around details. Contrary to common and widespread perception, Wannsee was not the time and place of the decision on the Holocaust.

Image 1: Villa at Am Großen Wannsee 56-58, Berlin, seen from the main entrance in January 2012. Since 1952, the villa has been used as a school hostel; only after decades of debate and failed attempts, it was turned into a memorial and educational site on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Wannsee Conference in 1992. Photo: Courtesy of Christian Mentel.

On the one hand, the conference protocol constitutes a key document for the understanding of the evolution of the Holocaust. On the other hand, it has become - on a symbolic level - "synonymous with the cold-blooded, administratively organized and delegated Nazi genocide", as historian Peter Longerich has put it. Both the factual and the symbolic aspects are challenged and attacked by a fringe group of writers calling themselves "revisionists". These authors claim to re-evaluate the Wannsee Protocol in a scholarly and fundamental way, and all arrive at the conclusion that the Protocol was either fabricated or that all "established" historians have misinterpreted it completely.

By calling themselves "revisionists", these authors intend to create the impression that they belong to the world-wide community of scholars. Contrary to this, almost none of the self-appointed revisionists are trained historians but rather in most cases, they are simply Holocaust deniers with outright sympathies for Nazi ideology. In scholarly-appearing books, some argue against Nazi Germany's responsibility for the outbreak of World War II, while others deny German war crimes either entirely or claim the numbers to be much lower, or that it involves isolated and regrettable incidents. One goal of most revisionists is to minimize numbers of victims or to relativize and count them with numbers of victims among the German civilian population. In any event, the focus of most revisionist attempts is denial of the systematic persecution and murder of people by the Nazi state, especially of Jews. In their writings, these authors portray themselves as independent "underdog" researchers asking all the critical questions academics and "established" historians allegedly do not dare ask. Revisionists do so by systematically deceiving their readers, while claiming to undertake historical and historiographical research along the lines serious scholarship has established.

The following sections will show how the revisionists' manipulations work, how their main arguments are structured and how they approach the topic. The goal is to provide an overview over decades of revisionist publications on Wannsee, brought forth mostly by German authors like Johannes Peter Ney, Roland Bohlinger, Udo Walendy and Germar Rudolf, but also elaborated by Robert Faurisson and David Irving. Three subject areas will be discussed: First, the transmission and publication of the Wannsee Protocol; second, the bureaucratic formalities and witness reports; and third, linguistics and semantics.

Area I: Transmission and Publication

To this very day, only one of a total of 30 copies of the Wannsee Protocol has been found. This is the copy of Martin Luther, who participated at the Wannsee Conference as Undersecretary of State of the German Foreign Office. And even Luther's copy - marked as "geheime Reichssache" (top secret) - seems to have slipped systematic destruction by the German authorities only by chance. Against this backdrop, the main revisionist line of argumentation is characterized by the statement that - contrary to official statements - there exist not just one, but a few - and different - copies of the Wannsee Protocol.

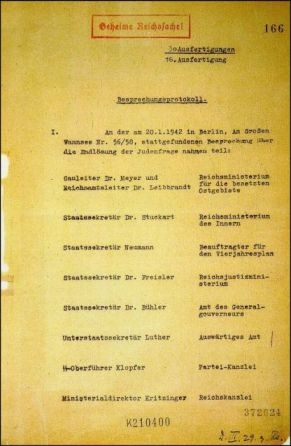

According to most revisionists, the Wannsee Protocol is a forgery. This forgery allegedly had been fabricated in the late-1940s by the Western Allies for use as evidence in the 1948/49 Ministries Case of the Nuremberg Trials. With forgeries like these, a genocide of European Jews should be ascribed to individuals as well as to the German state and people in general. In support of this claim, revisionists compare two images of the first page of the Wannsee Protocol. One image shows a photo of the one and only found copy (which is filed in the archives of the German Foreign Office; cf. image 2). The other image shows a facsimile of the Protocol, as it is printed in the 1961 book "Eichmann und Komplizen" (Eichmann and Accomplices) by Robert M. W. Kempner (cf. image 3). Comparing these two images, one immediately spots differences: Different rubber-stamps were used, in one image appear SS-runes while in the other "SS" is written using Latin letters, and a reference number has in one case been written by hand, and in the other case by use of a typewriter.

Image 2 (left): Click for an enlargement. Wannsee Protocol, p. 1, PAAA, Akt. Inl. II g 177, l. 166. (A PDF can be downloaded here: http://www.ghwk.de/deut/Dokumente/proto-1.pdf.)

Image 3 (right): Click for an enlargement.. Wannsee Protocol, p. 1, in: Robert M. W. Kempner, Eichmann und Komplizen. Zürich/Stuttgart/Vienna 1961, p. 133.

How can that be? If only one document has been found, how can two facsimiles of this one document differ? The answer of the revisionists to these questions usually goes like this: To arrive at a convincing final product, the forgers had to produce a number of draft copies that were brought to perfection step by step. Thus, the document filed at the German Foreign Office archives is not the only Wannsee Protocol there is; moreover it is only the best of various drafts that came about during a kind of evolutionary process of forgery. According to the revisionists, the facsimile Kempner has "accidentally" published in his book, merely constitutes one of these earlier drafts.

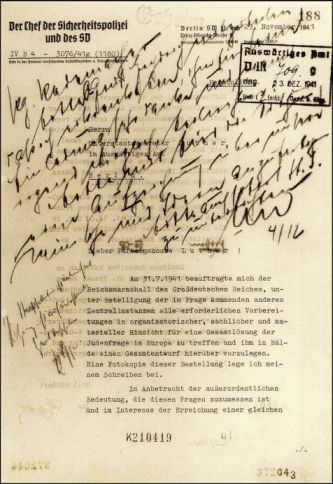

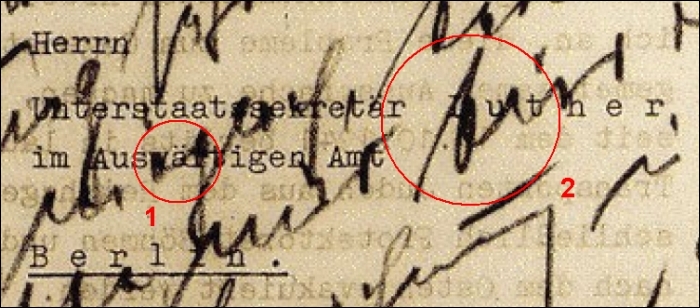

This line of argumentation is also followed by revisionists, when it comes to other Wannsee documents. Again, two images are compared: on the one hand, a photo of the original document filed at the Foreign Office archives, and on the other hand, the facsimile Kempner published in his 1961 book. In all instances, while there are no differences in respect to the content, there are differences elsewhere. Looking at the two images of the same invitation letter of November 29, 1941 (cf. images 4 and 5), it is clear that while different typewriters have been used, the hand-written notes on top of the typed text is identical. Once more: What was written first (i.e. the typed text), differs; in contrast: what was written afterwards on top of it (i.e. the handwriting), is the same. Evaluating these confusing observations, revisionists claim that only by means of manipulation is such a thing imaginable.

Image 4 (left): Click for an enlargement.. Reinhard Heydrich's Wannsee letter of invitation to Martin Luther, 29.11.1941, p. 1, PAAA, Akt. Inl. II g 177, l. 188. (A PDF can be downloaded here: http://www.ghwk.de/deut/Dokumente/luther_1941.pdf.)

Image 5 (right): Click for an enlargement. Reinhard Heydrich's Wannsee letter of invitation to Martin Luther, 29.11.1941, p. 1, in: Robert M. W. Kempner, Eichmann und Komplizen. Zürich/Stuttgart/Vienna 1961, p. 127.

Leaving the revisionist claims aside for a moment, what are the facts here? How can these differences - that ought not to be there - be explained? In fact, what Kempner published in his 1961 Eichmann book are not facsimiles of the original filed documents, but rather facsimiles of copies that were meant to emulate the original documents. In the case of the Wannsee Protocol, Kempner published a retyped copy of the original document. In case of the Wannsee invitation letter and others, Kempner published photomontages. How they were produced can be reconstructed on the basis of a close examination of the facsimiles. In a first step, the typewritten text of the original document had been retyped on a white sheet of paper. In a second step, all features of the original document that could not be copied that easily (i.e. the letterhead, signatures, rubber-stamps, handwritings), were transmitted to the typed copy. This obviously was done by means of retouching a photograph of the original document. While the typed text had been erased, only features like the letterhead and handwriting remained, and only these were copied on the newly typed text. At close inspection, one is able to spot instances where the retouching has been conducted imprecisely.

Image 6 (top) (showing a detail of image 4). Please pay attention to the position of the letter "ä" of "Auswärtiges Amt" (instance 1) and the position of the letter "u" in "Luther" (instance 2) both in relation to the respective hand-written notes on top.

Image 7 (bottom) (showing a detail of image 5). While the whole block of handwriting has been copied from the original document to the newly typed text inaccurately (note that the handwriting is moved a little bit up and further to the right compared to image 6), both instances 1 and 2 show imprecisely retouched remnants of the letters "ä" and "u" in the exact position that can be seen in image 6.

Fifty years after the publication of Kempner's book and given the author's death in 1993, we are not able to know for certain the reasons for doing so. But there are serious arguments that the then existing state of printing and reproduction techniques may be the reason, at least the techniques employed at Kempner's publisher Europa Verlag. Given the numerous images in Kempner's book, it can be stated that reproducing the photograph of a document was only possible within a very limited degree of quality. Also, other reproduction methods could not be applied on a general basis, because documents had to meet certain requirements. These requirements (e.g., black and clearly defined contours of the script) were not met by the Wannsee documents. Instead, they merely offered pale letters on either rough and yellowish paper or on sandwich, paper-thin, translucent paper that had been written upon on both sides. Thus, reproducing the original Wannsee documents in a readable way would not have been possible. Since the goal of Kempner and his publisher was to allow a general readership an authentic impression of what these documents looked like, the only way was to copy them one way or another and reproduce the copy.

Kempner and his publisher deserve to be criticized for this procedure. First, because it is generally highly questionable to alter and manipulate historical documents. Second, because they did not comment in any way on the nature of the facsimiles and the various different reproduction techniques they employed. Thus, readers were indeed deceived when taking the facsimiles as an exact reproduction of the original documents. This lack of transparency is the starting point for revisionists; it offers them the possibility to undertake all kinds of comparisons and to question the authenticity and validity of the documents. Nevertheless, it has to be pointed out that revisionists only compare images of documents - and not documents themselves. Comparing master documents would be the procedure of choice for any serious historian, because only then can certain features be investigated and only then could reliable statements be made on the nature of the documents in question. Because there are no master documents available of the facsimiles in Kempner's book, all revisionist accusations are just unfounded claims.

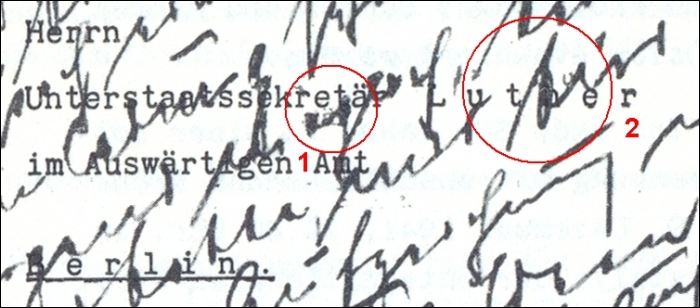

Image 8 (left): US prosecutor Robert Max Wasilii Kempner (1899-1993) during the Ministries Case 1948/49 at Nuremberg, Germany. Photo: USHMM/courtesy of John W. Mosenthal; Photograph #16820, http://digitalassets.ushmm.org/photoarchives/detail.aspx?id=1058615&search=ROBERT&index=29.

Image 9 (right): Cover of the book "Eichmann und Komplizen" by Robert M. W. Kempner, published by Europa Verlag Zürich/Stuttgart/Vienna in 1961.

There are many books out there that deserve harsh criticism; what then makes the facsimiles in this "Eichmann und Komplizen" book special and the revisionist claims so explosive? This is due to the fact that the book's author, Robert M. W. Kempner, was not just any old person. Kempner was part of the prosecution team at the Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals, and later served as US prosecutor in the Ministries Case, which was the second to last of the follow-up Nuremberg Trials. It was Kempner's team that discovered the Wannsee Protocol in March 1947, and it was Kempner who immediately used the document in interrogations and who introduced it at the trial. Thus, damaging the credibility and reliability of Kempner also means damaging the Wannsee Protocol itself. If Kempner (who fought the Nazis by means of the law while being employed as a legal advisor in Prussia's Ministry of the Interior and left Germany for the US in 1933 because he was Jewish) is questionable, then the Protocol is too.

Area II: Bureaucratic Formalities and Witness Reports

To appear trustworthy, revisionists present themselves as critical researchers, questioning all that others take for granted. Revisionists claim to stringently following the rules and methods of the historical profession; by doing so, they allegedly uncover mistakes, falsifications, forgeries and purposeful manipulations by so-called "established" historians. In order to make the point that all historians are wrong and only revisionists are able to get to the suppressed truth, they employ the historiographical tool of Quellenkritik, or the "critical assessment of sources". Usually, historians use Quellenkritik to determine the authenticity of sources and their reliability, and when they want to discover what can be derived from these sources. Pretending to investigate the features of the documents in a reasonable way, revisionists claim that the Protocol could not be authentic. According to them, crucial bureaucratic features that ought to be there are missing. They ask: Where is the rubber-stamp displaying the date when the document arrived at its destination? Where is the obligatory signature? Where is the obligatory reference number? Where is the name of the issuing authority and person and where is the date of issue?

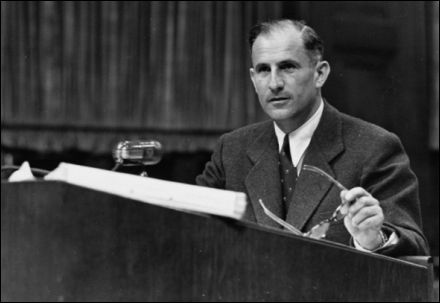

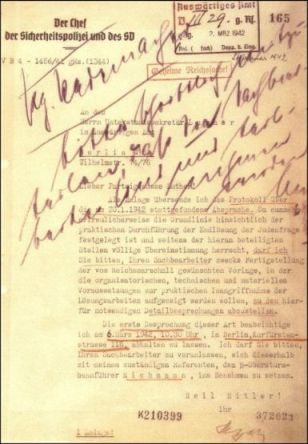

These questions are exactly the questions any serious historians would ask themselves when dealing with any historical document. But the revisionists' intentions are of a different kind - they employ these perfectly legitimate and necessary questions to deceive their readership and to convince them that the Wannsee Protocol is of a somewhat dubious nature. What is suppressed by the revisionists is the simple fact that the Wannsee Protocol was not prepared and not sent out as an isolated document by itself. Instead, it was an attachment to a letter of invitation for a Wannsee follow-up conference. It is on this higher-ranking cover letter (dated February 26, 1942; cf. image 10), where all the features can be found that revisionists complained about on the Protocol.

Image 10 (left): Click for an enlargement. Reinhard Heydrich's letter of invitation to Martin Luther, 26.2.1942, PAAA, Akt. Inl. II g 177, l. 165. (A PDF can be downloaded here: http://www.ghwk.de/deut/Dokumente/luther-versand-farbe-jpg.pdf.)

Image 11 (right): Click for an enlargement. Wannsee Protocol, p. 1, PAAA, Akt. Inl. II g 177, l. 166. (A PDF can be downloaded here: http://www.ghwk.de/deut/Dokumente/proto-1.pdf.)

Isolating two documents that need to be seen in context is all there is to this both simple and striking act of sleight of hand. Many years ago, the then director of the memorial site House of the Wannsee Conference Gerhard Schoenberner and historian Peter Klein pointed out this manipulation. The revisionists' response to being debunked is worth mentioning here. While they admitted that all the bureaucratic formalities were indeed to be found on the cover letter, they claimed that the Protocol ought to also show these formalities. Only if this were the case, could one be sure that individual pages or all of them had not been replaced. Moreover, contemporary regulations concerning top secret documents called for such a procedure. To be clear: According to revisionists, an authentic Wannsee Protocol would have to display on every single one of its 15 pages all bureaucratic formalities: all rubber stamps, dates, signatures, reference numbers, names, etc. Some revisionists even claim that because the margin width was not correct and the line pitch were not as they should be, the whole Protocol was not sufficiently authorized, not effective legally, and thus worthless for historiography.

It has to be stressed that all official regulations, norms, requirements and orders adduced by the revisionists against the Wannsee documents were never effective either for the issuing authority (Reich Security Main Office) or the receiving authority (Foreign Office). Again, this revisionist argument has to be considered as a crude attempt to damage the Wannsee documents by use of allegedly objective benchmarks - against the general assumption that Nazi bureaucracy had been perfect. Thus, even the slightest deviations from virtual norms are used as clear-cut "evidence" that the documents were forgeries, not one word is wasted on the question of how general requirements were put into real-life practice in respective areas of competency.

To complement this, another striking pattern of revisionist argumentation is used. It goes like this: Even if all of the - as shown above: absurd - revisionist demands in terms of authenticity and bureaucratic formalities were met, the document in question might still constitute a forgery. Because, after the end of the war, the Allies had access to all papers, rubber-stamps, typewriters and files, therefore all kinds of forged documents are possible - forgeries that are undetectable. In short, while exonerating files were systematically destroyed, incriminating and perfectly fabricated documents were created. With this surprise coup, revisionists consider all German files as potential forgeries, even if these files meet their own demands in terms of authenticity. Using this rationale, there is no possibility to determine the authenticity of any document and historiography is made impossible. However, it is telling that the suspicion that all captured German documents might be forged is only applied to those which are "incriminating". In contrast, captured documents which count for the revisionists as "exonerating" are naturally considered authentic.

Selecting sources in this tendentious way can be best observed when looking at how revisionists deal with witness reports of participants of the Wannsee Conference (some of them gave testimonies during police interrogations and while standing trial after 1945). In general, revisionists consider testimonies to be truthful and convincing when the participants claim not to have been at Wannsee, not to remember anything or to remember things differently and when they deny responsibility or claim not to have received the Protocol in the first place. It is worth looking at how revisionists deal with the testimony of Adolf Eichmann, who was more or less the only participant to deny neither Wannsee nor its purpose. Of course, during his Jerusalem trial and the pre-trial interrogations, Eichmann embedded his testimony on Wannsee in his general defense strategy, and historians should use it very cautiously. Nevertheless, Eichmann contributed valuable information on the development of the Conference as well as details. For example, he admitted his participation, that he was responsible for taking notes and writing the Protocol. He also admitted he contributed to the preparation and follow-up tasks, and confirmed that the topic was the genocide of European Jewry. Revisionists either keep silent about Eichmann's testimony, simply deny it or claim that Eichmann had been tortured and/or brainwashed. It is telling that none of the revisionists mentions that during his stay in Argentina in the 1950s, as a free man and without any constraints, Eichmann told the same things to his former SS comrade Willem Sassen during the course of an interview.

Area III: Linguistics and Semantics

At the center of another line of revisionist argumentation stands the wrong but widespread perception that the murder of all European Jews had been decided at Wannsee. The Protocol's authenticity is not denied, instead it is argued that all historians are misinterpreting it in a negative way without justification. Three steps are employed: First, revisionists suggest that the widespread opinion of the "Wannsee decision" is generally held and advocated by scholars. Second, revisionists try to destroy this very opinion. For example, they point to the fact that none of the participants at Wannsee was in a position to decide upon such a grave matter and, according to the Protocol, no such decision had been discussed or taken. Third, revisionists accuse historians collectively of knowingly misinforming the public and at the same time systematically suppressing the truth that there was no decision at Wannsee. Some revisionists take it even further and suggest that if historians lie about Wannsee, they may also lie about the Holocaust. This leads to the argument that if the Holocaust decision was not taken at Wannsee, there may be no decision at all - and where there is no decision, there can be no implementation. All of that is based upon a simple trick: to claim that the "Wannsee decision" is commonly held by scholars. This is not the case. Since the early 1960s at the latest, historians agree that no decision was taken at Wannsee and in countless books and articles published since, this overrated interpretation of Wannsee is addressed explicitly.

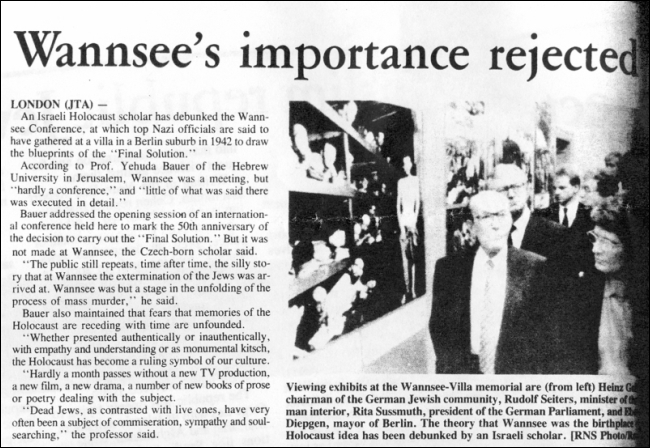

But how can revisionists claim the exact opposite? Again, by using a very simple sleight of hand. They pick out one historian speaking against the "Wannsee decision" and suggest that he is the only historian deviating from the otherwise "Wannsee decision" dogma. Yehuda Bauer is one such historian the revisionists picked. Time and time again, revisionists quote Bauer's statement in the weekly "The Canadian Jewish News" covering a 1992 historians' conference: "The public still repeats, time after time, the silly story that at Wannsee the extermination of the Jews was arrived at." (Cf. image 12.) The newspaper's coverage is not only lurid, it is plain wrong, when it reports the sensation that Bauer, as the first (and maybe only) historian, rejected and debunked an opinion that until this moment was commonly held by historians. Bauer was far from the first scholar who has rejected the "Wannsee decision" - as already said, this was accepted by historians for decades. But for revisionists, the short newspaper article provides a bonanza: referring to a Jewish historian quoted in a Jewish newspaper, revisionists claim that these days even Bauer accepts the revisionist position that Wannsee was fairly marginal and a "silly story" in general. This, of course, is not what Bauer said, and it is hardly surprising that all revisionists keep silent about Bauer's next sentence: "Wannsee was but a stage in the unfolding of the process of mass murder".

Image 12: Cutting from "The Canadian Jewish News", 30.1.1992, p. 8.

Beyond manipulating and omitting quotes in such ways, revisionists focus on the language of the Protocol itself. On the basis of style, vocabulary, syntax and figures of speech, revisionists try to argue that the Protocol could not have been written by a German native speaker. Or, if it was, the author surely must have been a German-Jewish emigrant out of touch with his mother tongue for some time. In other words: when investigating certain words and expressions which are allegedly uncommon in German, revisionists claim the Protocol is either a bad translation from American English, or it is influenced strongly by it. In any event, the Protocol's author could never be Eichmann or one of his staff, and therefore it can not be authentic.

The whole Protocol is scanned for anything that seems questionable in the eyes of the revisionists. Bureaucratic set phrases, figures of speech that are to be found in any official letter issued by authorities are marked as "un-German", just as all other nested, never-ending sentences that are hardly understandable. To linguists and students of German as a foreign language this argument must sound ridiculous - surely they would consider typically German what the revisionists call "un-German". Moreover, revisionists pick out single elements and comment on them in a more than a crude fashion. Among these comments, one can find: "No German man expresses himself like that, much less a high-ranking officer"; "Here we observe the 'New German' butchered by the American English; 49 years forestalled". Or, when commenting on the Protocol's list of Jews to be deported from Italy ("Italy, including Sardinia: 58,000"), one revisionist wrote: "In Europe, it was known what belonged to Italy. The list originated from Northern America, which is uneducated in regard of geography". Furthermore, a figure of speech that is uncommon in German as it is spoken in Germany, is claimed to be a bad translation from American English - disregarding the fact, that this particular figure is a common, and even formal, expression in Austria's variation of German. The absurdity of the revisionist claim is revealed when noting the fact that the author of the Protocol - Adolf Eichmann - lived in Austria during his childhood and worked there for many years thereafter. Thus, from a linguistic point of view, phrasings and expressions here and there typical of Austrian German are evidence for Eichmann's authorship of the Protocol, not against it.

A second revisionist line of argumentation in terms of language advances the notion that the Wannsee Protocol does not contain indicators of an intended genocide, but instead gives evidence that Heydrich had the same noble vision of establishing a Jewish state as the Zionists. The basis for this claim is the camouflage language the Nazis used: Instead of terms like "Ermordung" (murder), softer expressions were adopted: "natürliche Verminderung" (natural attrition), "entsprechende Behandlung" (suitable treatment), "Lösung von Problemen" (solution of problems) and not least "Endlösung der Judenfrage" (Final Solution of the Jewish Question). This technique can be observed best in the following paragraph (p. 7/8 of the Protocol, an English translation of the whole Protocol can be read here):

In the course of the final solution and under approriate [sic] direction, the Jews are to be utilized for work in the East in a suitable manner. In large labor columns and separated by sexes, Jews capable of working will be dispatched to these regions to build roads, and in the process a large number of them will undoubtedly drop out by way of natural attrition. Those who ultimately should possibly get by will have to be given suitable treatment because they unquestionably represent the most resistant segments and therefore constitute a natural elite that, if allowed to go free, would turn into a germ cell of renewed Jewish revival. (Witness the experience of history.)

Image 13: Clippings from the Wannsee Protocol, p. 7 and 8, PAAA, Akt. Inl. II g 177, l. 172 and 173. (A PDF can be downloaded here: http://www.ghwk.de/deut/Dokumente/proto-7.pdf and http://www.ghwk.de/deut/Dokumente/proto-8.pdf.)

This paragraph of the Protocol is essential and shows what Heydrich had in mind: not only deportation, but also forced labor as a method of murder. The survivors would be especially dangerous because they would be the most resistant. These would then have to be treated accordingly (meaning: killed), because if not, they would constitute the beginning of a new Jewish "super race".

What do revisionists make of this paragraph? They begin with admitting that the forced labor described above surely was hard. Immediately afterward, they relativize by way of arguing that this type of labor had been forced upon everybody by external circumstances during war times, as it always has been in wars. But still, the Nazi forced labor also served a higher end, because it functioned as an evolutionary process of selection. It helped to find a Jewish elite. This elite - the best of the best - would be indispensable, if after the war a Jewish state was to be built in the East according to Nazi plans. So, revisionists put forth that the Nazis intended to assist and train this Jewish elite in preparation for its role; in other words, they should be "treated accordingly".

What revisionists are doing here is transforming a program of murder for eleven million human beings into a process of state building. To accomplish this task, they decontextualize the more or less disguised intentions contained in the Wannsee Protocol and place them in a different context, giving them thereby other meanings. One thing indispensable for this is the - incorrect - claim that the term "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" always meant nothing but resettlement, and never extermination. Another necessary claim is that the so-called forced labor (which would be the reason for "natural attrition") was due to external and almost fateful constraints only, but not too well thought-out policy. Eventually, these alleged constraints are suggested to be "inflicted trials" that existed forever and which were accepted in all kinds of religions and ideologies, especially in Zionism. In the end, these "trials" would be nothing less than the will and an act of God, and thus embraced by Jews and Zionists. It is not difficult to see the parallel revisionists draw here: Basically, World War II and the Flood as well as Noah and Heydrich, are to be compared with one another.

Revisionists and the Wannsee Conference in Context

To conclude, it may be said that in revisionists' attempts to reframe the Wannsee Conference, the Wannsee Protocol as a historical documentary source only played a minor part. Far more important seems to be the "symbol" aspect: Wannsee as a code for systematic murder, for bureaucratically coordinated genocide, for the Holocaust in general. Once the symbolism of Wannsee is undermined or even destroyed, the image of the Holocaust is also affected. It would be too far-reaching to state that when revisionists attack Wannsee, they actually mean the Holocaust and only the Holocaust. Nevertheless, it is clear that before one can deny the Holocaust in a sophisticated way, one first has to deal with Wannsee. If the Holocaust is to be erased from history, the Wannsee Conference and the Wannsee Protocol have to be erased first.

In any case, revisionist attacks on the Wannsee Protocol are but one piece of a bigger puzzle and ought to be seen in this wider context. As indicated before, further pieces of this puzzle are the claims that the German Reich was not responsible for the outbreak of World War II, that the German crimes never had happened, or, if they did, they merely were part of regular warfare of which all war parties are equally guilty. These pieces add up to a revisionist conception of history, in which National Socialism, its leaders and agents are relieved of the burden of that which is morally reprehensible. Or, if they remain burdened by atrocities they committed, the weight should at least appear not heavier than the burden on all the others. Usually, revisionists start where historical research seems to be incomplete, where there are flaws, ambiguities and controversies. Even though the starting points and starting questions of the revisionists are often legitimate (as has been shown), their fallacious answers to these questions serve other purposes. What they intend is to replace the dominant negative image we have of National Socialism, by brushing aside with one sweep what generations of scholars all over the world have established.

It is important to bear in mind that revisionists are anything but a homogeneous group. But the one thing they have in common, no matter how different their methods, political world views and backgrounds, is anti-Semitism. Without the traditional anti-Semitic construct of a Jewish world conspiracy, revisionist writings are not possible. Underlying all revisionist writings is the idea that this alleged conspiracy is using false allegations of all kinds against Germany to dominate it and to gain money for Israel and the Jews. The implicit or explicit claim of a conspiracy of "World Jewry", which has at its command immense power and all means imaginable to make up and fabricate vast quantities of documents (the Wannsee Protocol being just one), is as irrational as the other revisionist line of argumentation: namely that for decades this Jewish conspiracy managed to influence all historians so that they - intentionally or unintentionally - misinterpret the allegedly innocuous Wannsee Protocol as proof of an intended genocide. Thus, irrationality and anti-Semitism constitute the basis of this kind of historical falsification.