Cultural Context, 1 Origin of the Word

Psychedelic, 4 Other Terms Proposed, 7 Varieties of "Psychedelics," 9 What are the Common Effects?, 11 What are the Benefits

to Humanity?, 17 Countercultural Influences, 19 Questions about Impurity and

Other Complications, 2i Use and Misuse, 25 Dealing with Difficulties, 26 Drawbacks of Psychedelic Usage, 30 Future Directions, 31

Preview

. . . a psychedelic drug is one which, without causing physical addiction, craving, major psysiological disturbances, delirium, disorientation, or amnesia, more or less reliably produces thought, mood, and perceptual changes otherwise rarely experienced except in dreams, contemplative and religious exaltation, flashes of vivid involuntary memory, and acute psychoses.

— Lester Grinspoon and James B. Bakalar, Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered

Mind-altering substances have been used in all societies except among the Eskimos and some Polynesians, and thus many of the plants discussed in this book have long and exotic histories. Much of the history, including early New World native use, is undocumented, and much is veiled in legend. We may never know whether Buddha's last meal was of mushrooms ("pig's food"). However, many scholars have now accepted the identification of Fly Agaric mushrooms as the inspirational "Soma" in the world's earliest religious text, the Rig-Veda, and evidence seems strong that ergot, an LSD-like substance, was the mysterious kykeon, used for more than 2,000 years in the annual ancient Greek Eleusinian Mysteries.

The anthropologist Weston La Barre characterized the use of mind-altering plants as being the source and mainstay of "the world's oldest profession"—that of the shaman or medicine man. He adds that such a specialist was "ancestor not only to both the modern medicine man or doctor and the religionist priest or divine, but also ancestor in direct lineage to a host of other professional types." Shamanism in the New World was fostered by indigenous Psychedelics that are powerful and quite safe. The Old World had to rely on less dependable, more erratic substances, such as hashish, belladonna, thorn apple and Fly Agaric mushrooms. It is now evident that the prescriptions of specific plants in the recipes in witches' brews of the Middle Ages was not as superstitious or random as earlier supposed.

After accompanying Columbus on his second voyage, Ramon Paul brought back word of cohoba sniffing among natives in Haiti. The earliest account of peyote was set down in 1560 in Bernardino de Sahaguns History of the Things of New Spain. In 1615, botanical notes made by the Spanish physician Francisco Hernandez about the mind-changing effects of morning glory seeds were published.

The first report on use of Amanita muscaria mushrooms among Siberian tribesmen didn't appear until 1730. Forty-one years later, a Swedish botanist accompanying Captain James Cook on his first voyage to the

2 Preview

Hawaiian Islands described kava-kava and the natives' ceremonial use of this substance. One year later, Sir Joseph Priestly, who first isolated oxygen, produced nitrous oxide (N^O). At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Baron Alexander von Humboldt, after whom the Pacific current is named, gathered together the first "scientific" report on the use of yopo snuff in the Amazonian region.

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, the pace of knowledge of psychoactive substances greatly quickened. In 1839, W. B. O'Shaughnessy introduced Cannabis indica into the Western pharmacopoeia, and five years later Theophile Guautier established Le Club des Haschischins in Paris. In 1851, the British explorer Richard Spruce first observed ayahuasca practices among the South American natives; four years later, Ernst Freiherr von Bibra published an account of seventeen plants capable of affecting the mind. Urging others to study this field, he described it as "promising for research and fraught with enigmas."

In 1864, die earliest description of psychoactive effects from the African bush Tabernantha iboga appeared. It wouldn't be until near the end of the nineteenth century, however, that peyote investigations eventually produced

Psychedelization of Society 3

the world's first psychedelic compound in crystalline form. Louis Lewin, another German important in the development of modern psychopharma-cology, traveled to the southwestern United States and brought peyote back to laboratories in Berlin. Eight years later, Lewin's rival, Arthur Heffter, isolated "mezcalin" from Lewin's specimens. After fractionating the alkaloids, or nitrogen-containing compounds, from this cactus, Heffter was able to locate the source of peyote's psychoactivity only by trying the various fractions himself.

The first account of the peyote experience from someone who had actually tried it appeared in 1896. This came from a distinguished author and Philadelphia physician, S. Weir Mitchell, who then forwarded "peyote buttons" to the prominent psychologists William James and Havelock Ellis. After ingesting them in his flat in London, Ellis called the resulting experiences "an orgy of visions" and "a new artificial paradise" (from the titles of his two reports). James, however,got a severe stomachache after eating only one, declaring that he would "take the visions on trust."

Scientific curiosity about peyote dimmed shortly after the turn of the century but was revived in 1927 by the French pharmacologist Alexandre Rouhier, who gave an extraction from the cactus to several students and published accounts of their "exotic" visions. A year later, Kurt Beringer published his 315-page study Der Meskalinrausch (Mescaline Inebriation). A year after that, an English monograph that attempted to catalog the elements of "mescal visions" was published. By this time, a continuing interest in what we now call psychedelic states was emerging. However, there was little indication yet that Psychedelics would eventually affect and enchant a great many people.

That eventuality began to take shape in 1938, when the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann synthesized d-lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate—LSD-25 In mid-April 1943, Hofmann apparently absorbed some of this compound through the skin of his hands and thus learned what animal tests had failed to show: that this substance was a mind-altering drug that had about 4,000 times the potency of mescaline.

In 1947, Werner A. Stoll, the son of Hofmann's superior, broadcast news of this discovery in scientific literature. Within two years, Drs. Nicholas Bercel of Los Angeles and Max Rinkel of Boston brought LSD to the United States.

The change that would take place in our thinking about molecules and their ability to affect the mind was catalyzed during the mid-1950s. In a slender, much noted book, Aldous Huxley described how his "doors of perception" had been cleansed by 500 milligrams of mescaline sulfate. In May 1957, Life magazine published the third part of a "great adventures" series with ten pages of color photographs: R. Gordon Wasson described how he had become one of the first two white men to be "bemushroomed." Since then, knowledge about Psychedelics has grown steadily, as have the numbers of people interested in them.

4 Preview

Origin of the Word Psychedelic

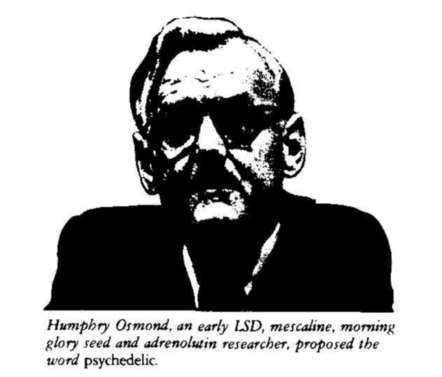

In the early 1950s, researchers Humphry Osmond and John Smythies wrote a paper about the mental effects of mescaline that came to the attention of Aldous Huxley, who invited Osmond to visit him if he should be in the Los Angeles area. Huxley's wife, Maria, was initially apprehensive about such a meeting, fearing that Osmond "might wear a beard." When Osmond did go to L.A. for a psychological conference, Maria was satisfied that he was not a Bohemian or a mad scientist (he didn't have a beard), and he stayed with the Huxleys. Maria, ironically, finally asked about getting some mescaline for Aldous. Osmond's reaction to the proposal was favorable, with one reservation:

The setting could hardly have been better, Aldous seemed an ideal subject, Maria eminently sensible, and we had all taken to each other, which was very important for a good experience, but I did not relish the possibility, however remote, of being the man who drove Aldous Huxley mad

In the literature then available about what we now call psychedelic drugs, the term most commonly used to describe the effects was psychoto-mimetic (meaning psychosis-mimicking). Yet it is evident from Huxley's description in The Doors of Perception that when he tried mescaline sulfate he was not going through some kind of "imitation psychosis." Huxley believed he had experienced something akin to mystical experience. He was considered an authority on the subject, being the author of one of the classics in this field, The Perennial Philosophy.

Osmond was already sensitive to the lack of an adequate term for the mental state induced by mescaline and LSD. He and his colleague Abram Hoffer had been observing LSD's effects in the treatment of acute alcoholism, and the states produced in their subjects were not as expected. Having read in the literature that LSD produced temporary psychosis, they had reasoned that such a substance could be used to touch off a kind of artificial and controllable delirium tremens. About 10 percent of those who experience d.t.'s never drink again.

Osmond and Hoffer tried LSD on two patients—one recovered, the other remained an alcoholic. They began to use LSD as regular treatment for their worst alcoholic cases, and it gradually became clear that recovery seemed to occur most commonly when the df.'s hypothesis was forgotten altogether. Hoffer has since commented:

... by 1957 it was apparent that even though many of our patients were helped by LSD, it was not its psychotomimetk activity which was responsible. In spite of our best efforts to produce such an experience, some of our subjects escaped into a psychedelic experience.

The new term came out of a regular correspondence that developed between Osmond and Huxley. Psychedelic—coming from the Greek psyche

from "Psychotomimettc" to "Psychedelic" 5

(soul) and delein, to make manifest, or deloun, to show, reveal—was first proposed in 1956 by Osmond.

Huxley took the lead, proposing words derived from roots relating to "spirit" or "soul." He invented the word phanerothyme and encased it in a couplet for Osmond's consideration:

To make this trivial world sublime, Take half a gramme of phanerothyme.

Osmond has since remarked that the word Huxley selected was too beautiful. He replied:

To fathom hell or soar angelic, Just take a pinch of psychedelic

Especially noteworthy about psychedelic is the presence of the first e— which varies from the ordinary way of combining Greek roots and thus dissociates this word from the misleading connotations of psychotic. Soul-manifesting belongs to the category of meanings that make sense in terms of contrast: fust as empty implies full, as child implies adult, so soul-manifesting implies an enlargement or actualization of consciousness. This point about Psychedelics is often hard to get across.

For better or worse, Osmond's psychedelic has been largely accepted as a description of the state produced by the substances to be discussed in this book.

Similarities to Various "Synonyms" 7

Other Terms Proposed

The word intoxication is said to have more synonyms than any other word in English, but none of them conveys the essense of a psychedelic mental state. To be psychedelicized is not at all the same as being drunk.

Intoxication by alcohol may hint at the experience that is characteristic of Psychedelics. Hermann Hesse speaks of alcohol in Steppenwolf as being capable of "lighting the golden trail" William James wrote about the impulse it gives to mystical feeling and "Yea-saying." However, it cannot approach the revelatory power of Psychedelics, and its well known drawbacks—loss of lucidity and sometimes of memory—put it in an altogether different category from LSD or mescaline. If any of the intoxication synonyms are to be used to describe soul-manifested states, the best is probably inebriation, because it lacks the connotation of poisoning contained in toxi-.

Hallucinogen is another word commonly used for substances producing a psychedelic experience. There is some truth in the characterization, for users often see "visions," especially with the eyes closed. However, most users consider the hallucinatory effect to be only one part of the experience— often a minor part. Even so, the man who formulated the word psychedelic used hallucinogen in the title of a book he wrote later with Abram Hoffer. Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann in their books about the botany and chemistry of these substances weight the various descriptive terms and settle on hallucinogenic and hallucinogen, while pointing out how inaccurate they are. The chemist Alexander Shulgin, after explaining that most MDA-like compounds evoke no visual imagery at all, labeled them "hallucinogenic" substances in his writings.

Even in the second edition of his book on the botany of Psychedelics, the ethnobotanist William Emboden retained the title Narcotic Plants. These psychedelic plants and related compounds are quite the opposite of narcotics: unlike opiates, they are basically stimulating, and they are non-addictive. (Psychedelics also differ from true stimulants; they increase lucidity but not, as with amphetamine, at the expense of psychological warmth.)

The most common psychiatric term for these botanicals and compounds has been psychotomimetic, stemming from a concept proposed in the late nineteenth century by the French doctor J.J. Moreau de Tours. He was the first to raise the hope that chemicals could produce insights toward the alleviation of mental illness. The hope was only partially realized. While the psychedelic state may have some similarities to psychotic ones, the differences are more numerous and more significant, a main difference being that the induced state is known to last only a short while. By the 1960s, few of the therapeutic projects using Psychedelics were attempting to bring about psychotic mental states. Yet the term still lingers, with papers describing blissful, beneficial results ascribed to some "psychosis-mimicking" drug.

Another psycho therapeutic term that has much currency, especially in Europe, is psycholytic, which has been specifically limited to refer only to low dosage use of Psychedelics in conjunction with therapeutic sessions. Shulgin

Preview

has compiled several more from the prominent psychotherapeutic literature: delirients, delusionogens, dysleptics, misperceptionogens, mysticomimetics, phantasticants, pharmakons, psychotaraxics, psychoticants, psychotogens and schizogens. Many observers have favored Louis Lewin's suggestion of phantastica, but this early formulation never caught on.

Several writers have turned to German or Sanskrit to find more appropriate words, but these have largely been ignored. More notable terms are peak experiences, a term popularized by the psychologist Abraham Maslow; altered states, popularized by the psychologist Charles Tart; alternative states, coined by Norman Zinberg; and cosmic experience, popularized in William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience.

The latest term proposed comes from the team of Ruck, Bigwood, Staples, Ott and Wesson, writing in the January-June 1979 Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. They feel strongly that "not only is 'psychedelic' an incorrect verbal formulation, but it has become so invested with connotations of the pop-culture of the 1960s that it is incongruous to speak of a shaman's taking a 'psychedelic' drug." They offer entheogen, calling it

a new term that would be appropriate for describing states of shamanic and ecstatic possession induced by ingestion of mind-altering drugs. In Greek the word entheos means literally "god (ibeos) within," and was used to describe the condition that follows when one is inspired and possessed by the god that has entered one's body. It was applied to prophetic seizures, erotic passion and artistic creation, as well as to those religious rites in which mystical states were experienced through the ingestion of substances that were transsubstantial with the deity.

Combining this Greek root with gen, "which denotes the action of 'becoming,' " they argue further for the suitability of entheogen:

Our word sits easily on the tongue and seems quite natural in English. We could speak of entheogen! or, in an adjectival form, of entheogenic plants or substances. In a stria sense, only those vision-producing drugs that can be shown to have figured in shamanic or religious rites would be designated entheogens, but in a looser sense, the term could also be applied to other drugs, both natural and artificial, that induce alterations of consciousness similar to those documented for ritual ingestion of traditional entheogens.

After being around for a couple of years, the term entheogen has entered the ethnobotanical literature and is about to be included in the Oxford English Dictionary. So far as popular usage is concerned, it doesn't seem to sit as easily on the tongue as originally claimed. For now, the term psychedelic, even if a little shabby and cheapened by overuse, will have to do. It is commonly understood, and since 1976 it has been included in the Addenda to Webster's Third International Dictionary. Here, with illustrations, is Webster's perception of this book's theme:

Chemical and Botanical "Clusterings"

Varieties of "Psychedelics"

Inspired by LSD and mescaline, the term psychedelic has since been used for many plants and synthetic compounds that produce similar changes in the ordinary functioning of consciousness. Exactly which substances should be included in this category and which should not has been a subject of considerable controversy for several reasons. Andrew Weil has discussed some of these considerations in the foreword to this book. The main difficulty is that there are several components to the psychedelic experience, appearing in different combinations and intensities with each drug. If one tries to index psychoactivity according to response to color, for example, then the MDA and marijuana compound-clusters would be excluded by some. (Many people would exclude marijuana because it has a different chemistry than most of the others and acts more subtly. However, for some people its use can be "inspiring" and it has widened "the scope of the mind" for many, Aside from the variations among mind-altering compounds, there are variations among users to consider. Some people seem especially sensitive to a very wide range of substances. Jean Cocteau felt quickening, mind- and soul-manifesting effects from opiates. The creative response he showed to those drugs is rare.

Well over a hundred compounds and plants are discussed throughout this book. Most are "indoles," a very small part of the world of chemical compounds. The non-indole Psychedelics also tend to "cluster" together in chemical families, though the dissimilarity among the various families is too great to make chemical composition a defining characteristic of a psychedelic substance. Botanical considerations are similarly confounding, Researchers in related fields have had equal difficulty in trying to delineate the action of Psychedelics — after decades of intensive investigation. Albert Hofmann, reacting to being known as the father of LSD, said: "It started off in chemistry, and went into art and mysticism."

Generally speaking, the Psychedelics considered in this volume touch a spiritual core in their users, have exhibited physical healing qualities, have been used ritualistically, facilitate creative problem-solving and change the

10 Preview

sense of time and spatial relationships. They are neither addictive nor toxic. Because their most significant action is mental, and thus fairly non-specific, Andrew Weil has characterized a psychedelic as being like "an especially active placebo," meaning that the user's response depends very much on his or her expectations. Art Kleps, much experienced with Psychedelics, was once asked, "What are the side-effects of LSD?" He said, forthrightly, "There are nothing but side-effects." The same could also be said about most of the substances to be discussed in this book.

Perhaps the easiest way to distinguish a compound as psychedelic is by means of two primary mental criteria: (1) that it induces enlargements in the scope of the mind, and (2) that these enlargements or new perceptions are influenced and focused by the user's "mind set" and by the "session setting." Osmond has provided a broad but usable definition of "enlargements," saying that "the brain... acts more subtly and complexly than when it is normal." "Mind set," usually shortened to set, refers to the user's attitudes, preparations, preoccupations and feelings toward the drug and toward other people in attendance at a psychedelic session; setting is a word for the complex set of things in a session's immediate surroundings: time of day, weather, sounds or music and other environmental factors, if results don't vary considerably with sets and settings, the compound almost certainly isn't a "psychedelic."

Most psychedelic substances fall into one of nine main compound-clusters. Each of the compounds in each cluster is unique. Many will be discussed ahead, but for the sake of conciseness emphasis will be put on just a few representatives from each group. The nine clusters will be presented in the order of importance to regular users. Here is a listing of these clusters and their representatives:

Cluster 1: The LSD Family, the major catalyst opening "the psychedelic age" and the archetype

Cluster 2: Peyote, Mescaline and San Pedro, a cluster once considered the most powerful, the "door opener" for Psychedelics in the 1950s

Cluster 3: Marijuana and Hashish, the earliest recorded Psychedelics, which exhibit synergistic action with all of the others

Cluster 4: Psilocybian Mushrooms, the easily identified, gently persuasive and yet powerfully mind-changing fungi containing psilocybin and/or psilocin that re-introduced an appreciation of psychedelic-effects in the late 1970s

Cluster 5: Nutmeg and MDA, the empathic compounds that create few "visuals," stimulating research into discrete psychedelic effects

Ouster 6: DMT, DET, DPT and Other Short-Acting Tryptamines,

a family of varying intensities but including the psychedelic that's the most impressive visually

Nine Major Families 11

Cluster 7: Ayahuasca, Yage and Harmaline, the "visionary vine" complex from the Amazon that is a "telepathic" healer

Cluster 8: Iboga and Ibogaine, the bush from Africa used in initiatory rites and by hunters to produce extended stillness, and its principal alkaloid that produces vivid imagery and stimulation

Cluster 9: Fly Agaric, Panther Caps and "Soma," the colorful, fascinating, sometimes frightful, legendary mushrooms that have been used shamanically and may, as "Soma," have provoked "the religious idea in homo sapiens" (R. Gordon Wasson)

What are the Common Effects?

Some of these substances cause nausea or giddiness upon ingestion, but the usual course for users is to reach an initial "high plateau" shortly after the onset of action; this plateau constitutes the first quarter or third of the experience. After that, there is often a build-up of intensity to the "peak" of the experience, usually occur ring about halfway through the session. During the second half of the experience, the effects gradually diminish, although mental stimulation may last in a more subdued fashion for some time. Memory of the experience is generally sharp and detailed, and physical after-effects are minimal. Feelings of elation are not uncommon and may continue for a day or longer after the experience has ended.

Whatever its duration, the experience widens the scope of awareness. One is transported internally to what Huxley called "The Other World"—a locale experienced spiritually, esthetical and intellectually. The environment perceived during ordinary states of mind isn't altered, but the perception of it is. This perceptual transformation of the external world is temporary, but the insights provided by it are often significant and lasting. The quality of psychedelic recognition can be compared crudely to seeing the same glass as half empty and then seeing it half full.

A CIA agent illustrates such a switch-over in awareness resulting from his LSD experience. As he told it to John Marks, the agent began

seeing all the colors of the rainbow growing out of cracks in the sidewalk. He had always disliked cracks as signs of imperfection, but suddenly the cracks became natural stress lines that measured the vibrations of the universe. He saw people with blemished faces, which he had previously found slightly repulsive. "I had a change of values about faces," he says. "Hooked noses or crooked teeth would become beautiful for that person. Something had turned loose in me, and all I had done was shift my attitude. Reality hadn't changed, but I had. That was all the difference in the world between seeing something ugly and seeing truth and beauty."

Generally, an initiate's first comment focuses on heightened awareness of internal and external sensations and on alterations in "unalterable

12 Preview

reality." Dr. Oscar Janiger, an early LSD researcher, listed these as "an unusual wealth of associations and images, the sharpening of color perception, the synesthesias, the remarkable attention to detail, the accessibility of past impressions and memories, the heightened emotional excitement, the sense of direct and intrinsic awareness, and the propensity for the environment 'to compose itself into perfect tableaus and harmonious compositions

Thoughts often seem to occur simultaneously on several "levels"—a dramatic demonstration of the mind's ability to resonate at different frequencies. The linear nature of ordinary thought is replaced with a more intuitive, holistic and "holographic" approach to understanding reality. Many investigators have compared the logic of this "Other World" to that of dreams and other functions often associated with the right hemisphere of the brain.

Description of the psychedelic experience as a kind of dream state where one is wide awake and remembering or as a state in which right hemispheric brain functions are amplified is consistent with most experiential reports. These are usually full of comments about enhanced sensitivity to rhythm as well as new appreciations of music and dance.

Many observers feel that the rhythmic aspect of this experience marks a progression into deeper "stages." Robert Masters and Jean Houston describe four stages of deepening awareness in their The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience.

Walter Houston Clark, another LSD pioneer, is among those who speak of Psychedelics as mainly "catalysts" to feelings, understandings and thinking. A psychedelic "adds nothing to our consciousness, but it brings to the surface many parts of our consciousness that had been lying dormant most of our lives." Recently Clark gave out 140 questionnaires asking users about the nature of their experiences. He noted that "there wasn't a single one" of those responding who didn't mention at least one—and most mentioned several—of the characteristics in "the universal core" of mysticism, as compiled by a leading religious scholar. Clark's conclusion from his own observations and from those of the respondents

has been that the typical person, wherever he's found, turns out to be a mystic when you go right down to the bottom of his personality. What I'm saying is that all of us here in this room are potential mystics. As William James said in his chapter on mysticism, "Given the appropriate stimuli, mysticism will come to the surface."

Aldous Huxley had a similar point of view. After writing about how use of Psychedelics had deepened his feeling for the spiritual, he received a letter from Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk and noted poet. Questioning the validity of drug-induced mystical experience. Merton asked about distinctions that might be drawn between mystical and aesthetic aspects. In January 1959, Huxley responded with his evaluation of the "deeper" aspects

FUNCTIONS OFTEN ASCRIBED TO THE BRAIN'S

RIGHT LOBE

the craftsman

the dancer

feminine

the artist

mysterious

light

relational

intuitive

oblivious to time and space

passion

artistic endeavor

spatial awareness

balance

non-linear, non-analytical awareness of one's own body

musical ability

the "dark" side

the dreamer

recognition of faces language tone & accent

holistic mentation

14 Preview

of the psychedelic experience (reprinted in his Moksha writings, edited by Horowitz and Palmer). He stated that

there are those whose experience seems to be much more than aesthetic and may be labeled as pre-mystical, or even, I believe, mystical. I have taken mescaline twice and lysergic acid three or four times. My first experience was mainly aesthetic. Later experiences were of another nature and helped me to understand many of the obscure utterances to be found in the writings of the mystics, Christian and Oriental. An unspeakable sense of gratitude for the privilege of being born into this universe. ("Gratitude is heaven itself," says Blake—and I know now exactly what he was talking about.) A transcendence of the ordinary subject-object relationship. A transcendence of the fear of death. A sense of solidarity with the world and its spiritual principle and the conviction that, in spite of pain, evil and the rest, everything is somehow all

right-----

Finally, an understanding, not intellectual, but in some sort total, an understanding with the entire organism, of the affirmation that God is Love. The experiences are transient, of course; but the memory of them, and the inchoate revivals of them which tend to recur spontaneously or during meditation, continue to exercise a profound effect upon one's mind----There is a feeling—I

speak from personal experience and from word-of-mouth reports given me by others—that the experience is so transcendently important that it is in no circumstances a thing to be entered upon light-heartedly or for enjoyment. (In some respects, it is not enjoyable; for it entails a temporary death of the ego, a going-beyond.)

Some have criticized this and similar descriptions from Huxley on the ground that most people don't have the intellectual and imaginative resources that he brought to this experience; his response, they claim, was atypical. This objection has some validity, but Walter Clark has indicated chat most users do have experiences along similar lines. What individual users make of them is influenced by their knowledge, religious feeling, willingness to accept new perceptions as valid, circumstances under which the psychedelic was taken, and the amount of attention subsequently paid to the insights or feelings aroused.

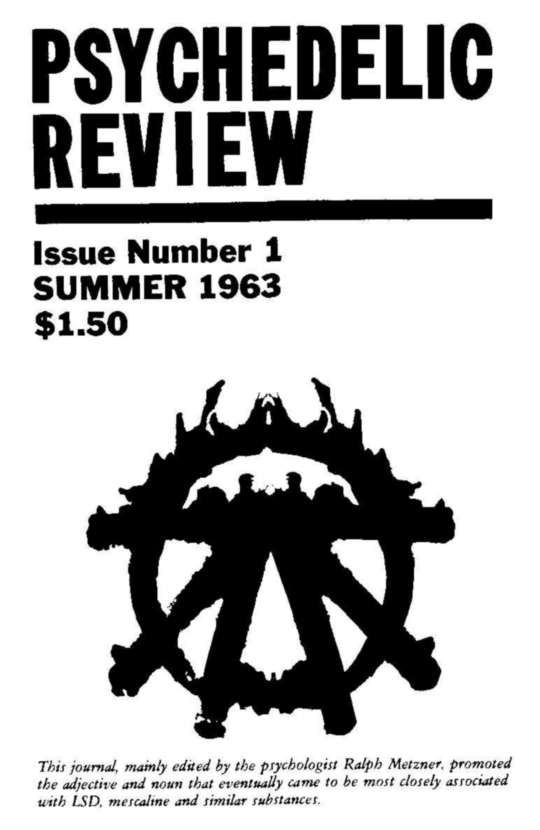

Almost no one who has taken a powerful psychedelic has come away unimpressed. Psychologist Ralph Metzner observed over a period of years that people awakened by Psychedelics to the myriad possibilities for human consciousness often go on to pursue other ways and methods of increasing awareness. Osmond, writing in the Annals of the New York Society of Medicine, described the awe that is a frequent sustained effect:

Most subjects find the experience valuable, some find it frightening, and many say that it is uniquely lovely. All, from [anthropologist J.S.] Slotkin's

Valuable/Frightening/ Uniquely Lovely 15

unsophisticated Indians to men of great learning, agree that much of it is beyond verbal description. Our subjects, who include many who have drunk deep of life, including authors, artists, a junior cabinet minister, scientists, a hero, philosophers, and businessmen, are nearly all in agreement in this respect. For myself, my experiences with these substances have been the most strange, most awesome, and among the most beautiful things in a varied and fortunate life. These are not escapes from but enlargements, burgeonings of reality ....

Andrew Weil, who has sought out and tried most of the Psychedelics, recently told a gathering that their greatest impact for him—and he hopes for society—has been the elimination of limitations. Here are some of his comments:

I had begun to do hatha yoga. I was experimenting with being a vegetarian and I had never done any body-work before, and, for me, yoga was very discouraging. I found that there were a number of postures that not only could I not get in, but there seemed to be no hope of getting in. There was one in particular that was really a great stumbling block to me, and that was "The Plough," I would lie on the floor and get my feet over my head, and when my toes were about a foot from the floor 1 would get an excruciating pain in my neck. I felt so bad I could hardly get out of the position 1 was in, I tried for at least four or five weeks to work at that every day, but there was no progress. I made a little progress at first, and then hit what seemed to be an absolute limit defined by this pain in my neck. I was really on the verge of giving up. I thought that I was too old (I think I must have been twenty-eight then) and stiff. I thought I had waited too long to do yoga; it was just an impossibility.

Well, we all took acid on this perfect day. There were puffy clouds, butterflies and all the usual things on a wonderful spring day. I was feeling so good that at some point I thought, "Well,gee, I ought to try doing some yoga postures." And I lay down, and I tried The Plough. When I thought I had about a foot to go, my toes touched the ground—and I couldn't believe it! I raised my legs and lowered them, and kept raising them and lowering them, and not only was there no pain in my neck, it felt great!

I burst out laughing, it was so wonderful—and suddenly I had this feeling that nothing was impossible, that all the limits I had imagined just weren't there suddenly. And, "If I could do that, why couldn't I do all these other things that I never thought I could do?" In fact, I began doing some of them.

The next day, still elated from this experience, I tried to get into The Plough. And, a foot from the floor, there was that excruciating pain in my neck again. But there was a difference. I knew I could do it now,and the fact that I knew it was possible motivated me to keep working at it. If I had not had that experience, I would have given up. There was no reason to think that I would have continued in that direction. Having had that experience changed what that meant for me.

Origins of Mythology/Consciousness Research 17

What are the Benefits to Humanity?

Many benefits are conferred upon humanity by these extraordinary substances that affect thinking and feeling; illustrations abound for nearly every psychedelic.

The first crest of the psychedelic movement, in the 1960s, coincided with a general recovery of the religious impulse, seen especially in the revival of interest in Eastern religions. A new flexibility in religious belief and spirituality came about at a time when influences such as existentialism had convinced many that "God is dead." The psychologist Stanley Krippner has suggested that the Psychedelics were "the single most important factor in bringing back dedication to this country."

A sense of harmony spread with the use of Psychedelics, along with a new appreciation of non-violence. However, these religious feelings weren't organized; they occurred spontaneously within individuals and were accepted largely as recognitions common to people who had seen beyond ordinary states of consciousness. A large percentage of users became vegetarians after an eight- or ten-hour experience made them feel that they couldn't eat flesh any more.

Mary Bernard raised the question of the possible religious origins and consequences of Psychedelics in The American Scholar:

When we consider the origin of the mythologies and cults related to drug plants, we should surely ask ourselves which, after all, was more likely to happen first: the spontaneously generated idea of an afterlife in which the disembodied soul, liberated from the restrictions of time and space, experiences eternal bliss, or the accidental discovery of hallucinogenic plants that give a sense of euphoria, dislocate the center of consciousness, and distort time and space, making them balloon outward in greatly expanded vistas?

Perhaps the old theories are right, but we have to remember that the drug plants were there, waiting to give men a new idea based on a new experience. The experience might have had, I should think, an almost explosive effect on the largely dormant minds of men, causing them to think of things they had never thought of before. This, if you like, is divine revelation ....

Looking at the matter coldly, unintoxicated and unentranced, I am willing to prophesy that fifty theobotanists working for fifty years would make the current theories concerning the origins of much mythology and theology as out-of-date as pre-Copernican astronomy.

Psychedelics have brought us closer to an understanding of the human mind, as is evidenced by new directions in formal studies of the brain. Krippner, who has visited many investigators in fields dealing with "alternative realities," has remarked that the main impact of Psychedelics from 3 scientific point of view was to get people interested in research into consciousness:

not only with Psychedelics, but with sleep, dreams, biofeedback, hypnosis, meditation, etc. Many of the very prominent consciousness researchers today, though few will admit it, were turned on to this whole experience by their early acid trips back in the 1960s.

1 8 Preview

Krippner described the magnitude of these effects while introducing a panel discussion in July 1981 on the social and cultural implications of consciousness research:

I think it would be no exaggeration to compare the discovery of LSD, and the use of LSD, by such pioneers as Dr. [Stanislav] Grof, whom you heard last night, to the Copernican revolution, the Darwinian revolution, and the Freudian revolution.

The Copernican revolution took the human being's planet out of the center of the universe and out of the center of its own solar system and put it on the periphery The Darwinian revolution placed the human being in direct descent from lower animals. The Freudian revolution pointed out that much of human motivation is unconscious, rather than conscious. Human beings were still holding on to that little bit of conscious motivation that they had until Albert Hofmann came along with LSD, suggesting to us that what little conscious motivation we have is chemical in nature and that it can be influenced very radically by chemicals.

This was premature, because within the last few years there have been many experiments with endorphans and other neural transmitters which support this view. The chemical basis of behavior, of memory, of cognition and of perception is now taken for granted more than it was back at that time.

For individuals, Psychedelics have facilitated problem-solving and creativity, encouraging many users to take more responsibility for their destiny. Duncan Blewett, an early Canadian researcher, has described the effect of Psychedelics on personality as akin to "thedevelopment of self-awareness," but which is the beginning of a progression or "move from being a self-aware organism to a state of being where an individual responds spontaneously in Zen terms " These drugs often encourage the conviction that reality is self-determined rather than predestined. Many aspects of (his change in attitude are discussed in Timothy Leary's books, particularly his Neurologic, Exo-Pfychology and Changing My Mind, Among Others. Many users agree with his notion that these substances promote "self-actualization" and that their use facilitates "re-imprinting" of more desirable attitudes.

Many of the medical benefits from Psychedelics haven't been explored very fully, but even the limited work to date has given us a new understanding of the psychosomatic aspects of ill health. As will be pointed out ahead, most of these substances have extensive healing histories that are worthy of further study. A model for such study may be found in the approach taken by the recently formed Beneficial Plant Research Association in Carmel, California, which is especially interested in the tonic and other benefits ascribed to the use of coca leaves. This group's "Coca Project" has gone through the red tape to get approval for a comprehensive investigation of coca's efficacy as: (a) treatment for painful and spasmodic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, including gastritis and peptic ulcers; (b) a topical anesthetic in dentistry; (c) a treatment for acute motion sickness; (d) a treatment for laryngitis; (e) a substitute stimulant for coffee in patients who are dependent on coffee but

The Chemical Bans of Behavior 19

cannot tolerate its irritant effects on the gastrointestinal or urinary systems; (f) a regulator of carbohydrate metabolism in cases of hypoglycemia and diabetes; (g) an adjunctive therapy in programs of weight reduction and physical fitness; and (h) a rapid-acting antidepressant.

As a result of their mental experiences, many users have become more aware of what the body's needs are and how to take care of them, and these people have given impetus to the renaissance in organic farming, herbal lore, health foods and many other nature-inspired practices for improving the functioning of the human body.

Psychedelics, which once helped create a "generation gap," have also had the effect of improving family relationships, as happened for psychologist Richard Alpert. After taking a large dose of LSD one night, he went to a family reunion the next day. His brother asked, "How's the nut business?" This "digging at each other" was typical of his family; it "was our form of love. It was a Jewish, middle-class tradition."

Still affected by his psychedelic state, Alpert saw an arrow coming out of his brother's mouth, slowly crossing the table. In his mind, Alpert reached up, took this arrow and put it next to his spoon. Then he "picked up a heart and blew this over" to his brother and said, "Gee, your kids are getting so incredibly big and handsome." A look of confusion crossed his brother's face, because Richard wasn't playing the family game. After some silence, his brother sent over another arrow: "Well, you're certainly not growing much hair, are you?" Alpert's response was to reach up for this arrow and set it down on the table. He sent back another heart shape: "Boy, your wife i« getting more beautiful all the time."

Alpert says that by mid-afternoon all of the family—husbands and wives and kids gathered in the living room—were experiencing the family bond in a new way, enjoying just being together. "There was this incredible love feast." Nobody wanted to leave. When it was time to break up, everybody stood outside in the street, "and for a long time nobody could get into their car to go. Nobody wanted to break the love bond that had been formed." The gathering, by all reports, "in fact had been a totally unique experience in everybody's life."

His experience and reports of similar effects from many other users caused Alpert to become interested in the nature of "contact highs," where one person conscious in a special way can bring about changes in consciousness of other people. This phenomenon suggests that psychedelic mind expansion is not solely the result of chemical stimulation.

Counterculture Influences

The development in the 1960s of an "alternative culture" was the result of many influences, chiefly the Vietnam war, the availability of psychedelic drugs, and the prosperity that enabled "war babies" to become "flower children." Thousands and then millions of people began to experiment with

20 Preview

Psychedelics, ending the earlier phase when the population of users was limited mainly to Native Americans and experimental subjects. Several important consequences were to flow from this change.

For many people, taking a psychedelic became something of a political act. Experimenting with marijuana, for instance, was a "statement" that the government's case against it was exaggerated. Benevolent experiences with marijuana led many users to question authority in other areas as well; if the government misinformed people about marijuana, what about our role in the Vietnam war? What else might be in error? Use of stronger Psychedelics, no doubt, also contributed to people's skepticism.

Psychedelic festivals called "Be-ins" were the natural outgrowth of the feelings of unity experienced by early users, as were many efforts at communal living. Whereas previously Psychedelics were usually taken by only one person, often in a clinical setting, the new emphasis was on open, uncontrolled, large-scale enjoyment of expanded consciousness. Consequently, much of the public became frightened at the massiveness of this "movement," fearing that some alien force was stealing its children away. Alpert, viewed by many at the time as a leading psychedelic "Pied Piper," blames the over-exuberance of early LSD missionaries for triggering a general hysteria about Psychedelics, especially Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, who conducted "Acid Tests" where LSD was available in a punch.

We thought we had a few more years of sneaking under the wire with legitimacy before the whistle got blown. But Ken made them blow the whistle. I mean, the day after the San Jose "Acid Test," the big headline in the paper was about a "Drug Orgy," Then the legislators had to act. Their hand had been forced.

Once legal restrictions were enacted, promising scientific studies were curtailed. James Goddard, head of the Food and Drug Administration at the time, declared that alleged creative and other benefits from Psychedelics were "pure bunk" Janiger, reflecting on the stigma suddenly thrust on LSD researchers, said that he had come to be perceived as

a villain who was, you know, trying to seduce people into taking it. It was absolutely bizarre! From the heroes, we were suddenly some creatures who were seducing people into changing their consciousness.

The use of Psychedelics on a mass scale released enormous creative impulses that continue to affect us all. Whether or not one uses these substances, they have permeated society down to the grass roots. Many had hopes that these powerful compounds could be absorbed in society in legitimate ways, thereby changing the character of use and avoiding unnecessary paranoia. Ivan Tors, probably best known as the producer of the "Flipper" TV series, was one who gave up LSD once the laws banning Psychedelics went into effect:

Releasing Creative Impulses 21

My upbringing was such that the thought of doing something illegal would put me in a negative state, and thus interfere with my LSD experiences. 1 feel this is true of others as well, and may account for many of the untoward reactions of those who use LSD in the underground.

Questions about Impurity and Other Complications

By the beginning of the 1960s, four powerful psychedelic agents were available, though not yet widespread: peyote, mescaline sulfate, psilocybin and LSD-25. Marijuana and hashish were more widely available. Most of those who swallowed the stronger substances up until about this time probably ingested pure Psychedelics. Sandoz Pharmaceuticals spent about $3 million in sending out samples of LSD and psilocybin for investigative purposes. Mescaline was available from a variety of chemical houses, and in most states peyote could be ordered through the mail.

Were there any negative results? Surprisingly few. In I960, Dr. Sidney Cohen, attached professionally to UCLA and the Veterans Hospital in LA., wrote sixty-two doctors who had published papers on use of LSD and mescaline/peyote, asking about dangers of such psychedelic treatment. Forty-four replied with detailed comments, covering more than 5,000 patients and volunteers given Psychedelics in more than 25,000 sessions. The dosage range in the case of LSD went from 25 meg. (rnillionths of a gram) to 1,500 meg.; 200 mg. to 1,200 mg. was the range for mescaline.

In this survey, not a single physical complication was reported—even when Psychedelics were given to alcoholics with generally impaired health. This result was somewhat unexpected, because it had been assumed previously that a diseased liver would produce an adverse reaction. There was also a surprisingly low incidence of major mental disturbances. Despite the profound psychic changes that occur when a person is under the influence of 1SD or mescaline, psychotic and other adverse reactions lasting longer than forty-eight hours developed in fewer than 0.2 percent of the cases reported. The attempted suicide rate was just over 0.1 percent. Not one case of addiction was reported, nor any deaths from toxic effects.

If this sampling of 5,000 early psychedelic users is divided into two classes—mentally sound volunteers and people who were mentally unstable— the findings seem even more encouraging. Among those who volunteered for LSD or mescaline experiments, a major or prolonged psychological complication almost never occurred. In this group, only one instance of a psychotic reaction lasting longer than two days was reported, and there were no suicides. Among the mentally ill, however, prolonged psychotic states were induced in "one out of every 550 patients." In this group, "one in 830 attempted suicide," and one carried the attempt through.

In evaluating these statistics, it should be pointed out that at the time of this survey (I960) the proper uses of these substances for therapy were not

22 Preview

well understood. Some of the negative reactions, furthermore, were deliberately brought about, since many of the doctors were trying to produce "model psychoses" in their patients, and some even gave the drugs in conjunction with electroshock treatment. Nevertheless, such statistics clearly demonstrated that the dangers in using these powerful drugs were far less than had been expected.

Since this 1960 survey, new and more appropriate techniques have been introduced, and the methods of administering Psychedelics have been refined. These advances have resulted in the reduction of potential hazards. Dr. Hanscarl Leuner, an outstanding European expert on psycholytic therapy, has since had this to say about Cohen's findings:

Cohen ... showed very well how low the relative risk of the therapy is, if it is carried out responsibly by qualified doctors. Thus, we actually are threatened less by adverse results, or severe complications, than we had to assume at the start. Our experience has shown that this risk can be reduced to practically zero in a well-institutionalized therapy, as in our clinic. This holds for the activation of depressions and schizophrenic psychoses, as well as attempted or successful suicides.

As a result of psychiatric and psychological experiments, many mental patients and volunteers (an example of the latter is the novelist Ken Kesey) were exposed to the effects of LSD and other Psychedelics. Sandoz deserves most of the credit for this, because it distributed LSD and psilocybin to licensed researchers all over the world, mostly free of charge. This was done with hopes that a researcher somewhere would find a medical use for these novel compounds.

But then the picture changed. Books like Huxley's, first-person accounts from a number of others (like the nutritionist Adelle Davis, writing about Exploring Inner Space under the name Jane Dunlap), and additional research such as that with psilocybin by the psychologist Timothy Leary and associates at the Concord, Massachusetts prison system, led before long to heightened expectations. Many millions of people developed a desire to experience a "psychedelic trip"—in contrast to a "psychotomimetic" one, which appealed to few. Many people, who lacked access to certified dispensing physicians, soon determined that they would get some one way or another. As psychiatric experimentation expanded into personal experimentation and interest in Psychedelics spread, the supply of pure drugs manufactured by pharmaceutical houses ran short of demand. The underground chemists went to work. The first underground lab to attract public attention belonged to two partners, Bernard Roseman and Bernard Copely, who were arrested in 1962 for "smuggling" 62,000 doses of LSD because of a story they told to misdirect attention from the fact that they themselves had made this. (Production of LSD at this time, however, was still legal.) The disturbing part about Roseman's account of this affair—in his book LSD: The Age of Mind—was his mention that their LSD turned into a blackish, slimy

Experience in the 1960s 23

material. He tried it anyway and was impressed by the effects, and so the two of them packaged it for sale. The purity of Psychedelics on the black market has been an issue ever since.

By 1965, the first massive manufacturing and distributing operation had come into being—Owsley's marvelous "tabs." Yet Stanley Owsley came from a background of interest in amphetamine, and some users soon raised questions as to whether he liked to add "speed" to the product. Bruce Eisner, who has written much about the question of psychedelic purity, talked with Owsley's lab assistant, Tim Scully, and believes that speed was never added.

October 16, 1966 is an important date in psychedelic history—it was the day when California outlawed LSD (an action soon to be repeated by the federal government), and the day of the first "Be-ins," occurring both in San Francisco and New York City. Soon after, Sandoz—the only legitimate source of. LSD and psilocybin—stopped supplying these chemical agents to American investigators. Sandoz turned over the remainder of its stockpile in its New Jersey facility to the National Institute of Mental Health, which in turn soon curtailed research programs using psychedelic drugs in human subjects from more than a hundred down to a grand total of six. The chances of anyone getting "pharmaceutically pure" LSD rapidly dwindled.

In 1967, DOM—also called STP—was introduced to the counterculture but soon withdrawn amid controversy over excessive dosages and impurities. It still appears on rare occasions, sometimes sold as STP but often disguised by a less stigmatized name. "Orange Wedge" appeared in early 1968, in strong dosages and available internationally; it was followed in early 1969 by another massive psychedelic production effort—the "Sunshine" trip. In both cases, allegations sprang up that these products had been adulterated with speed, STP, strychnine, etc.

By the early 1970s, doubts about the purity of underground products were common—and for good reason. There were weak "blotters' of LSD, requiring four or five to "get a buzz." At about this time, nearly a hundred drug analysis organizations, the most prominent being PharmChem in Palo Alto, began to examine the quality of underground psychedelic products. What they found was not reassuring. Quality control was non-existent, A summary from PharmChem for the year 1973 showed the following:

Of 405 samples said to be LSD, 91.6% were as alleged, 3.4% had no drug at all, 3% were actually DOM, PCP and others, and 2% had DOM, PCP and methamphetamine in addition to LSD.

Of 127 samples said to be marijuana, 89.7% were as alleged, 6.3% had no drug at all, 1.6% was nicotine, and 2,4% had PCP and cocaine in addition to marijuana.

Of 64 samples said to be THC, none were as alleged, 95.3% were PCP, and the rest were LSD and other substances.

2 A Preview

Of 185 samples said to be mescaline, 17.39% were as alleged, 7.6% had no drug at all, 61.69% were LSD, 11.49% were LSD + PCP, and there were three that were PCP and two others as well.

A single sample of DMT was as alleged.

Of 59 samples said to be MDA, 71.29% were as alleged, with the rest (28.8%) composed of DOB. DOM, 2,5-DMA, PMA, PCP and LSD + PCP.

A single sample said to be MMDA was found to be LSD. A single sample of ibogaine was as alleged.

Of 35 samples said to be PCP, 84.99% were as alleged, 12.1% had no drug at

all, 39% were marijuana.

If marijuana products are excluded, just over 55 percent of so-called "Psychedelics" tested out as claimed (501 out of 906 samples). More than 9 percent contained no psychoactive substance at all; a full 34.5 percent were assayed as some entirely different mind-altering chemical. Although many of these samples may have been sent in for testing because there was already some question about their content, this rundown indicates a serious problem with the purity of black market Psychedelics from that era.

The early 1970s was the worst period of misrepresentation. Siva Sankar recorded findings that were even worse when better analytical equipment was used:

Marshman and Gibbins tested 519 samples of street drugs for which the vendor's claimed composition was available. Of the samples alleged to be LSD, 44ty contained LSD with 2 or more contaminants, or even were mixtures of intermediate chemicals resulting from unsuccessful attempts to synthesize LSD. None of the drugs alleged to be mescaline contained mescaline. Lundberg, Gupta and Montgomery analyzed several alleged street drugs, mostly from the California area. Of 96 samples sold as psilocybin, only 5 contained psilocybin. The rest were either LSD or mixtures of LSD and phen-cydidine.

It's unfortunate that underground manufacturing and distribution of Psychedelics developed this way. The purity of a complex chemical is difficult to test, and doubts about the purity of an untested chemical can create paranoia, multiplied easily while in a psychedelic state. Furthermore, an impure dose may well encourage fundamental misinterpretations by the novice as to the nature of the psychedelic experience.

All the results I have ever seen indicated that "Sunshine" (as an example of a suspect psychedelic) was pure LSD-25. The PharmChem listings above show virtually all the acid examined to have been pure, though the matter of contaminants may not have been examined very thoroughly. PharmChem found a quantitative average for acid during 1973 of 67.25 meg.; during 1974,96 meg. It was mescaline and psilocybin that were generally found to be misrepresented. This situation has since improved, but there is still good cause for being wary.

Doubts by the 1970s 25

While most attention has focused on purity to account for the bummers experienced by many using black market acid, it should be noted that the psychedelic molecules are delicate and should be handled gently in transport. Also, most oxidize fairly easily and should be kept away from light, heat and water.

Use and Misuse

The question of use and misuse has always been a difficult one in regard to Psychedelics, and it can never be answered satisfactorily because the experience depends so much upon circumstances, attitudes and the presence or absence of a ritual. These points will be emphasized throughout this book: the traditions of shamanistic use, the "Good Friday experiment" and the work at Spring Grove Hospital will be given as examples for setting up good rituals. If users think of the psychedelic experiences as sacramental, as a special event to be prepared for, the results are bound to be better than if they're viewed as "recreational," as a way to stave off boredom.

Timothy Leary goes to the heart of this matter in an essay entitled "After the Sober, Serious, Safe and Sane '70s, Let Us Welcome the Return of LSD." He restates a controversy that raged among the pioneers of the psychedelic age as to whether these substances should be reserved for use by only a few or whether they were appropriate for "democratization, even socialization." In any event, the choice was probably beyond the control of the early users. Summing up what he sees as the results from "seven million Americans" having used LSD, Leary concludes:

Our current knowledge of the brain and current patterns of LSD usage suggest that the Huxley-Heard-Barren elitist position was ethologically correct and that the Ginsberg-Leary activism was naively democratic. Our error in 1963 was to overestimate the effect of psychological set and environmental setting. We failed to understand the enormous genetic variation in human neurology ....

LSD and psilocybin did seem to be fool-proof intelligence-increase (I!) drugs because our experiments were so successful! In thousands of ingestions we never had an enduring "bad trip" or a scandalous "freak-out," Sure, there were moments of terror and confusion aloft, but confident guidance and calm ground-control navigation routinely worked. Our mistake, and it was a grave one, was that we failed to understand the aristocratic, elite, virtuous self-confidence that pervaded our group ....

It was the Heisenberg Determinacy once again We produced wonderful, insightful, funny, life-enhancing sessions because we were a highly selected group dedicated to the scientific method. We were tolerantly acceptant of ambiguity, relatively secure, good-looking, irresistibly hopeful and romantic So we fabricated the realities which we expected to create. We made our sessions wonderful because we were wonderful and expected nothing bin wonder and merry discovery!

26 Preview

Psychedelic usage can be life-changing, particularly in terms of one's relationships with others. The spiritual insights achieved may make it difficult to live in the same way one has in the past. Leary's guidance as to who is most likely to gain from the experience is worth keeping in mind (it is put with his characteristic flamboyance):

ACID IS NOT FOR EVERY BRAIN .... ONLY THE HEALTHY, HAPPY WHOLESOME, HANDSOME. HOPEFUL, HUMOROUS H1GH-VELOCITY SHOULD SEEK THESE EXPERIENCES. THIS ELITISM IS TOTALLY SELF-DETERMINED. UNLESS YOU ARE SELF-CONFIDENT SELF-DIRECTED, SELF-SELECTED. PLEASE ABSTAIN.

Dealing with Difficulties

Dr. Stanislav Grof provides a useful start in evaluating the possibility and meaning of a turbulent experience with a psychedelic:

The problem is the definition of a "bummer," Difficult experiences can be the most productive if properly handled and integrated.

The best set and setting and quality of LSD cannot guarantee a "good" trip, if this means easy, pleasant, uncomplicated. The problem is more management of (he experience than the experience itself. We can increase the productiveness of sessions.

Although this book isn't designed as a session guide for tripping, it is appropriate here to provide some background on minimizing tight moments that may develop. The management of a session and the role of "guides" are treated in Masters and Houston's The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience, in Leary, Metzner and Alpert's The Psychedelic Experience and in Cohen

and Alpert's LSD.

John Beresford, a psychiatrist who has had much experience with Psychedelics since the early 1960s, outlines a basic strategy:

Confrontation is precisely what should be avoided when a person who has taken LSD shows signs of agitation or depression or in some other way is manifesting resistance to the natural flow of the experience. What the person helping can do then is search for and suggest an image or idea which complements the image or idea which acted as the springboard of resistance. "Hie resistance is undone and the normal flow of the session can proceed.

Art Kleps, with more than two decades of interest in Psychedelics, makes many suggestions in his Boo Hoc Bible about the often crucial role-played by the guide:

As long as there are complaints about or fears of loss of ego the ego is not lost, nor is it diminished in any simple way. You are not, in this situation, dealing with a six year old child, who can easily be put off or led down the garden path. The ego at bay is a mobilized ego, alert to all danger, suspicious of your every move and word. Always assume that the [user ] can "see right through you," no matter how bizarre his behavior. Be honest. If you honestly think distraction is called for, then say so. For example, "Well, if questions like thai

Psychedelic "Tight Spots" 27

are bothering you, why not look at some of these pictures instead?" Don't pretend a sudden interest in something you are not really interested in at all. As for saying, "Try not to think about it" or something of the sort, well, try not to think of a purple cow yourself and see how much luck you have ....

Let's come right out with it: unless you are enlightened,don't bother try ing to guide Ivory Sessions—sit by if requested to do so, but make no pretense of being anything more than a servant, "ground control" or whatever the hell you want to call it. The fact of the matter is that fakery is impossible in this situation anyway; there are no standards; there is no third party, no precedents, no law. It all depends, and it depends on nothing constructible. Circum-stances, and circumstances only.

Finally, here is a list of some "do's" and "don't's" that Bonnie Golightly and I compiled in our LSD—The Problem-Solving Psychedelic:

1) User is in control and can change direction!. Under the influence of such substances, the user is nor simply adrift, a tourist cast off at the mercy of the elements and in the grip of forces that cannot be influenced. He or she is, instead, yet in control and can change directions. Because of the overwhelming nature of what occurs, however, this may not be easy to remember.

The user under the influence of a psychedelic can function normally and can also alter the experience. This should be fully grasped before taking this type of drug. Once into a session, the user should take time out and practice "reversing" sensations. Water may taste like wine |ust by thinking it; a light object can be made to feel heavy; or another's glistening tears can be turned into a dry-eyed expression of joy. When sufficiently skilled, the user will be able to "select hallucinations" at will.

2) Preparing for "take-off." For the initiate, some difficulty may be encountered in "take-off," since the transition is comparable to a jet thrust. Care should therefore be taken to reduce rigidity and awkwardness. The best approach for entering "inner space" gently is made with the aid of a "fluid." not-too-highly structured selection of music and simple breathing exercises, or possibly a massage, since a tense, tight attitude may grow out of "waiting for something to happen."

3) "Going with " negative nates. During the eight or ten hours of altered reality under the influence of most Psychedelics, much that is shocking or distasteful may occur within the user, especially unpleasant fantasies of a physical nature. Cardiac specialists as well as other doctors often direct their heightened psychedelic sensitivity to their bodies and witness in surgical detail the actions of internal organs. These physical scrutinies also preoccupy the layperson, of course, and birth experiences—being born or giving birth—are within the ordinary line of psychedelic events. As mentioned previously, disorientation with regard to time may terrorize the most valiant.

Many frightening "hallucinations" are mainly subjective experiences with little basis in everyday fact. If the user wants them to "go away," the best remedy is to dispense with the natural impulse to "fight them." "Going with them" or "giving one's self over" disperses the unwanted vision and the "screen" is cleared for something else.

28 Preview

Facing terrifying psychedelic events may call for courage and stamina in early sessions.

4) Boosting the experience. If resistance remains high, the experience may become repetitious, leading up to a crucial point but without a breakthrough. The user vacillates—hot and cold, back and forth, endlessly affixed to the same treadmill. He or she cannot make decisions, and has been through all this many times before.

In such instances, "boosting" may be called for. An additional dosage is usually enough to "break the set" and move the user off his or her plateau. Dr. Duncan Blewett gives the rationale:

One of the things we discovered is that if you don't give a large enough dose of the drug, a person gets into a son of interim position, with one foot in the camp of the usual frame of reference and the other in the camp of unhabitual perception. The user finds it impossible to make a

break between these two-----But if a large enough dose of the drug is

used, so that the person is propelled rapidly out of the old context and cannot maintain the self-context as previously, then—rather than becoming more uncomfortable as you would think—he or she becomes much more comfortable and able to accept as valid this new and novel way of seeing the world.

A reason for the occasional vortex-like recurrence of the same material seems to lie in the fact that the drug effects come in waves, and if the user is allowed to persist in one area too long, he or she may be caught in an undertow. The favored method for breaking through this "hang-up" is to change the subject matter completely—with the intention of returning to it later if it seems worthwhile. If the recurrent material is deliberately brought up again after some time has passed, the subconscious will have had a chance to devise other approaches and the insight level will probably be more acute. A good technique in such instances, borrowed from hypnosis, is to suggest that in a specified length of time the user will return to the problem and then be able to resolve it.

5} Recognizing physical symptoms. The development of physical symptoms (such as coldness, nausea, pressure on the spine, restlessness, tingling, tremors or "a pain in the kidneys") is often the body's way of evading psychedelic effects. With peyote, and to a lesser extent with sacred mushrooms or morning glory seeds, these effects may be attributed to the drug, but with LSD and most other synthetics such symptoms are most frequently a sign of resistance. The guide should in such cases recognize these symptoms as an indication that the drug is about to take effect, and should reassure the user that these physical symptoms will soon pass, with "the psychedelic experience" taking their place.

6) Reacting to verbal stimuli. Another evasion of the full psychedelic experience may involve over-intellectualizing what happens and talking on and on throughout the session. Because language depends upon familiar ways of thinking, reliance on words keeps much that is non-verbal from developing and restricts the psychedelic experience. To carry on a lengthy conversation confines "psychedelia" even further, since the user when questioned or spoken

Breaking Out of an Undertow 29

to is somewhere "out in orbit" and must then come back and touch down before replying. For the average person, a period of verbalization may not develop into a problem, but a rigidly defensive person, on the other hand, may use words to avoid the experience, and as time passes may become increasingly desperate, or even aggressive, reacting with hostility towards the guide. A variety of menacing motivations may be imputed to the guide. In such a situation the guide should refuse these various "ploys," gently reminding the user what he or she is there for.

7) Physical comfort. If terror grips the user continuously during the session, physical comforting may lend the needed reassurance. But as pointed out previously, this is a delicate matter unless the guide is certain that the user will not misinterpret the gesture. Because attendant psychedelic distortions may seem too vile or alien to be shared, the user who has lodged in a crevasse can most successfully be brought out, if other means have not been satisfactory, by the guide's taking him or her into the arms and soothing the frightened tripper.

8) Counter-diversion. If "reversing" any disturbing "hallucinatory" material has not dispelled anxiety, counter-diversion should be attempted. The user should be encouraged to try some appropriate physical activity such as dancing, keeping time to music, playing the piano or even gardening! Taking deep breaths and paying attention to the lungs as they expand and contract is quite effective. Such diversionary efforts will in all probability become the new focus of attention.

9) Extra resources. The skilled guide always has extra resources up the sleeve or is capable of fast, imaginative thinking. One example, which can serve as a pattern for the latter, occurred when a user decided she was made of metal and was unable to move. "Oh, you're the friendly robot in that TV serial," the guide remarked genially, and as the user was familiar with the program referred to, she immediately "recognized herself" and began moving gaily in a deliberate parody of an automaton's gyrations.

Leary had an amusing and instructive episode to recount along these lines. An electronics engineer had taken psilocybin and was reacting with great anxiety,

... his traveling companion was unable to calm him down. The psychologist in charge happened to be in the bathroom. He called to his wife, who was drying the dishes in the kitchen: "Straighten him out, will you?" She dried her hands and went into the living room. The distressed engineer cried out: "I want my wife!" and she put her arms around him, murmuring: "Your wife is a river, a river, a river!" "Ah!" he said more quietly. "I want my mother!" "Your mother is a river, a river, a river!" "Ah, yes," sighed the engineer, and gave up his fight, and drifted off happily, and the psychologist's wife went back to her dishes.

10) Eliminating unpleasant "hallucinations," Pinpointing the source of an unpleasant "hallucination" can eliminate it rapidly. One user, for instance, convinced that the house was on fire, said he could actually see his "charred limbs" in the ruins. He was set straight when he was shown a burned-out candle in an ashtray, still smokir^ because the wax had been set afire by cigarette butts. Another person was able to deal with distasteful psychic material when

30 Preview

told that he was "merely a visitor passing through a slum" and that "a better neighborhood would soon emerge."

11) "Game-playing." Crises do sometimes arise even in well planned sessions. If the user is unable to cope with them in a sober manner, the guide may suggest "game-playing." The user should be instructed to think of himself or herself as a versatile actor who must portray a character in a serious role, stand aside and let the play begin.

12) Getting borne. If the user has insisted upon talcing a stroll through heavy traffic, wants to drive a car or undertakes some other ill-advised pursuit, and if the guide has been outwitted or lost contact, the user should remind himself or herself that what is happening is due to the psychedelic taken and that its effects will, in time, wear off. Finding the way home is not an impossible feat, and the user should try to recall, step by step, how it was done the day before. Since evaluating distance may be difficult, it is important to obey all traffic signals rigorously in crossing streets, taking a cue from the surge of the crowd. Any inclinations towards bizarre behavior should be curbed, bearing in mind that the mission is simply to get home.

If the user has been driving a car, upon realization of the situation it's important to park as soon as possible, and take a cab, a bus or proceed on font Although the user may not believe it, most people will have no idea of his or her condition, either through their own preoccupations or the simple fact that it is not always easy to detect psychedelic drug behavior.

In point of fact, "runaway" and out-of-control sessions are extremely unusual. Once a psychedelic experience has been completed, the carry-over depends on where the stepping stones have been placet! or if the desired bridge has been reached. Ideally, time should be allowed for relaxation in "normal reality" to let the subconscious integrate its new insights. This is the time to put the "psychic house" in order, to speculate about what has been resolved and what remains to be resolved.

Drawbacks to Psychedelic Usage

Most users of Psychedelics claim that the effects from these substances on their lives have been beneficial. Many, in fact, state that they have been influential in producing the most meaningful and positive experiences of their lives. On the other hand, a small number of people who have used Psychedelics have had what they consider to be long-term negative effects.

In the days when these drugs were taken with less awareness of the psychedelic experience's potentials, there were undoubtedly drug abuse tragedies. Much of the bad press for psychedelic drugs originated from these occurrences. The illegal status of LSD, psilocybin and MD A came about as a result of the dangers inherent in self-experimentation during the 1960s.

A variety of psychedelic substances are now widely used throughout our society, even though it is usually illegal to buy, sell or even possess them. Although this author believes that their dangers have been vastly exaggerated {and are much less than the dangers of alcohol), abuse of these substances

Handling Crises 31

can and has occurred. Almost all of this at present can be characterized as involving unintelligent use.

Because alterations in consciousness produced in psychedelic states can possibly lead to impairment, care in choosing the circumstances, dosage, quality of drugs, companionship and related matters should always be exercised. Thoughtless and reckless use of these compounds is a violation of their positive, indeed sacred, characteristics.

The best psychedelic experiences are life-changing and life-enhancing. Throughout this book appear both a) enthusiastic statements in regard to the benefits, and b) warnings where appropriate about dangers. Attention paid to these matters will help bring the time when Psychedelics will be mote widely appreciated in our society for their medical, therapeutic, creative, religious, insightful and relationship-enhancing capabilities. Future Directions