1902 Encyclopedia > Railway, Railways (Railroad) > Railway Construction: Tunnels

Railway, Railways

(Part 13)

C. RAILWAY CONSTRUCTION (cont.)

Tunnels

The relative cost of rock-cuttings and cuttings in clay do not greatly differ; for, not only does the vertical rock-cutting require less excavation than the wide yawning earth-cutting of the same depth, with extended slopes, but when it is executed, the rock-cutting is not liable to the expensive slips which sometimes overtake the other. For depths exceeding 60 feet it is usually cheaper to tunnel.

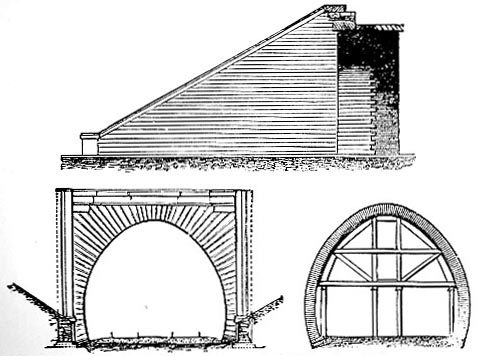

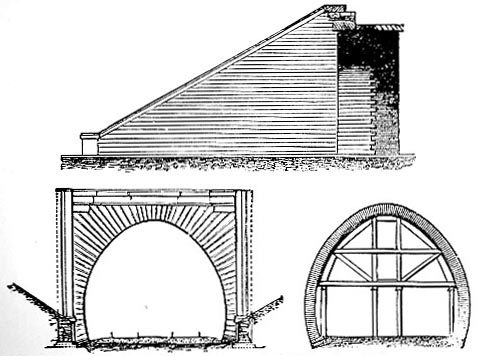

Fig.16. Tunnel under Callander ridge, on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway.

The tunnel (see fig. 16) under Callander ridge near Falkirk station, on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, is a fair representation of tunnels as usually constructed. It is lined with brick 18 inches thick, founded on stone footings of greater breadth, in order to throw the load securely upon the subsoil, as shown in the transverse section. The sides and roof of the tunnel are curved from footing to footing, so as effectually to resist the inevitable external pressure of the earth, to a span of 26 feet in width and a height of 22. The sectional view shows also the centering or timber framing employed in the building of the tunnel, which was braced diagonally and transversely to resist the unavoidable inequalities of pressure without alteration of form whilst the arch was in course of construction. Externally the entrances are built of stone, and the flank walls are 3 feet in thickness, with counterforts at intervals. This tunnel is not straight, but is formed on a curve of 1 mile radius, and is 830 yards, or nearly half a mile in length.

The Kilsby tunnel, on the London and Birmingham Railway, was rendered necessary by the opposition raised to the line passing through Northampton. It is driven 160 feet below the surface and is 2398 yards in length, 30 feet in width, and 30 feet high, constructed with two wide air-shafts 60 feet in diameter, not only to give air and ventilation but to admit light to enable the engine-driver in passing through it with a train to see the rails from end to end. The construction of the tunnel was let for the sum of £99,000, but, owing chiefly to the existence of unseen quicksands, the tunnel is stated to have actually cost nearly £300,000, or £125 per lineal yard.

The Box tunnel, on the Great Western Railway, between Bath and Chippenham, was another difficult and expensive work. It is about 70 feet below the surface, and is 3123 yards in length, or rather more than 1 3/4 miles; the width is 30 and the height 25 feet. Where bricked, the sides are constructed of seven and the arch of six rings of brick, and there is an invert of four rings. There are eleven air-shafts to this tunnel, generally 25 feet in diameter.

Fig. 17. Tunnel under the Mound, at Edinburgh.

The tunnel under the Mound of Edinburgh (see fig. 17), on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, supplies an excellent illustration of tunnels formed with inverts,—that is to say, inverted arches built under the rails. The figure is a transverse section, showing the truly circular arch of the tunnel, 28 feet in diameter and 20 high above the rails, built of brick 3 feet thick, stiffened with counterforts externally, and with ribs of masonry internally, founded on a solid bed of mason-work, with an inverted arch to distribute the weight. The Mound was a mass of loose earth and rubbish on a boggy soil, hence the necessity for the invert arch, on which the tunnel may be conceived to float.

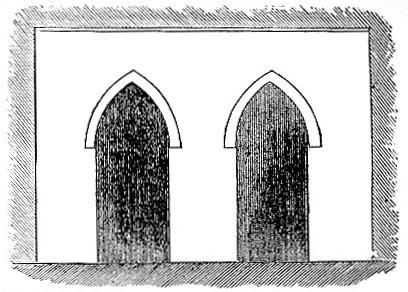

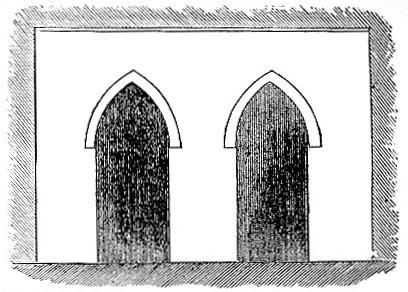

Fig. 18. The Shakespeare tunnel, on the South-Eastern Railway.

The Shakespeare tunnel, or, more correctly, double tunnel, driven through the Shakespeare Cliff near Dover, on the South-Eastern Railway, is in fact two narrow tunnels, carrying each one line of rails (see fig. 18), 12 feet wide and 30 in extreme height, through the chalk, separated by a solid pier or wall of chalk 10 feet thick. The chalk is of variable quality, and the greater part of the tunnel is lined with brick, strengthened by counterforts at 12 feet intervals, which carry the weight of doubtful beds of chalk. The tunnel is 1430 yards, or upwards of three-quarters of a mile in length, rising westward with an inclination of 1 in 264. The tunnel being within a short distance of the face of cliff, the material excavated was discharged through galleries about 400 feet long, driven in from the face of the cliff, into the sea,—the first operation being to run a bench or roadway along the face of the cliff. There are seven vertical shafts from the surface, averaging 180 feet deep.

There were in 1857 about 70 miles of railway tunnelling in Great Britain, or 1 mile of tunnel for 130 miles of railway. There are now (1885) probably at least 100 miles of tunnelling. The cost of tunnelling has averaged £50 per yard. The longest tunnel is the Woodhead, at the summit of the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire Railway, being 3 miles and 60 feet long. The tunnelling on the Metropolitan Railway is noticed below, p. 239.

Read the rest of this article:

Railway, Railways - Table of Contents

|