RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Amazing Stories, June 1942, with "The Man Who Was Two Men"

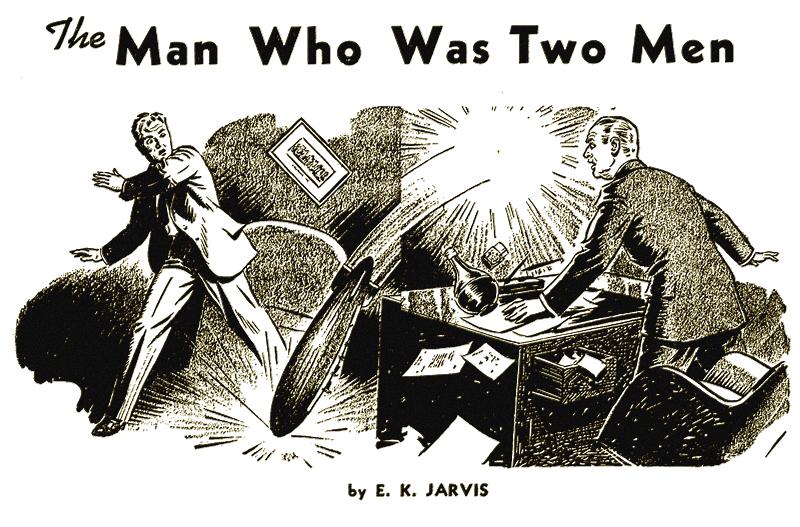

With crashing force the tiny model smashed into the floor.

It was an incredible secret this crazy inventor

claimed to have solved—the way to overcome gravity.

"BUT you will have to wait your turn, sir," my secretary protested.

Her voice sounded strained. The never-ending pressure of work accounted for that. Everybody in Washington, from the man in the White House on down, was working day and night, trying to buy back the precious minutes so carelessly wasted in the golden years, trying to barter blood and sweat for time. This was especially true in my division of the War Department.

The door to the waiting room was open a crack and I heard the commotion start. I knew what was happening. Another crazy inventor had made a discovery so important he just couldn't wait to tell the War Department all about it! That's my job. I'm head of the harassed engineers who see the long-haired lads from the tiny machine shops and the hidden home laboratories who think they have discovered something important. The things they bring to us! I've looked at everything from plans for a flying submarine down to ideas for dropping spitting cobras behind the enemy lines. No matter how wacky the idea is, we see the inventors just the same. We never can tell when some timid little guy, with dandruff on his collar and dreams in his eyes, will come tip-toeing into the office with the idea that will win the war!

Jim Vaughn, an engineer, and officially my assistant although he knows more about electrical engineering than I ever hope to know, was sitting beside my desk. We were deep in the plans for a new type of storage battery that didn't use acid and probably didn't store electricity either. When the commotion started in the waiting room, Jim looked at me and groaned.

"When this war is over," he said firmly, "I'm going to move to a land where all inventors are throttled as soon as they're born. I'm going nuts!"

"Me and you both," I said.

Wham! The door of my office was kicked open and over the protests of my angry and frightened secretary a man came striding into the room.

"My name is Welty," he said, glaring at me. "Richard J. Welty. Are you William Edgar?"

Most of the inventors who come to us look as if they need a square meal. Also, they are usually shy and reticent. There wasn't anything shy about Welty and if anything he looked over- fed. He was a big man, six feet or better, with a strong voice and a commanding bearing. His chin was decorated with a pointed beard, he had heavy black sideburns, and he was wearing, of all things, a wide-brimmed black hat and a long black cape. A fawn- colored vest, pin-stripe trousers, and spats over patent-leather shoes completed his clothing. To me, he looked like a barker on vacation from his post in front of a medicine show and at any moment I expected him to open the heavy suitcase he was carrying and start trying to sell me some Indian snake oil.

"Are you William Edgar?" he repeated, his eyes snapping. "If you are, say so. But don't waste my time."

"I'm William Edgar," I said. "And if I am wasting your time, it is scarcely my fault."

Looking past him, at my secretary, I asked, "Is this gentleman next on the list of appointments?"

"No, sir," she said. "He isn't. He doesn't have an appointment at all. He forced his way past me. Shall I call the police?"

She was hot and I didn't blame her. I was getting hot myself but I couldn't afford to show it.

"If you will see my secretary, she will give you an appointment. Others are also waiting to see me and she will give you an appointment as soon as possible. Is that satisfactory, Mr. Welty?"

It damned well better be satisfactory. It was the best I could do. Everybody who comes to this office is seen.

"It's not in the least satisfactory," Welty answered. "I can't wait around here until some little dime-a-dozen clerk decides to see me. My time is valuable."

Even more than what he said, the way he said it got under my skin. I didn't mind too much being called a dime a dozen clerk for I know I'm a mighty small cog in a mighty big machine. The wheels of the war department would go right on turning without me. My face probably got red but I held my temper.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Welty. We're undermanned and overworked. You will have to take your turn."

MY voice may not have been cold enough to freeze an iceberg

but it would certainly have frozen icicles. I expected it to put

the chill on this barker.

It didn't. He looked a hole through me. "Buster," he said. "Do you want to win this war, or don't you?"

"Uh—My name is Edgar. Mr. Edgar, in these circumstances."

"Okay, Mr. Edgar. You still haven't answered my question. Do you want to win this war, or don't you?"

One thing about this drip, he kept pitching. The tone of my voice would have curled the whiskers of an ordinary mortal; but not Welty. He came back for more.

"Yes, I want to win the war," I said. "When shall I advise the general staff that you will take care of winning the war for them?"

That should have stopped him. It would have stopped me. It would have stopped a Congressional investigating committee. It would have stopped the FBI long enough for the boys to take a couple of deep breaths. But it didn't stop Welty. It just made him look thoughtful.

"You can tell the big shots we can do it in six months," he said, after a moment's thought. "We might do it in three months, but to be on the safe side we had better plan for six. Always on the safe side, that's me!" he laughed.

I don't know why I put up with this lad. I don't know why I didn't throw him out of the office, or call the cops to do it. I think his colossal effrontery awed me into inaction. Talk about an over-developed ego, nerve, and gall, this man had them! He was the living, walking, breathing image of the great I. He left me without the breath to act.

And before I got my breath, he acted.

With one hand, he swept the papers off my desk. Papers, books, folders, drawings, everything—went on the floor. Without as much as a "By your leave—" he swept my desk clean. Inkwells, blotters, my favorite pen, my pipe, and my pipe rack, all of them hit the floor.

Then he lifted the heavy suitcase he was carrying and plunked it down on the desk. Flipping open the catches, he began to unbuckle the leather straps that circled it.

I didn't know I was standing up until Jim Vaughn spoke.

"Easy, Bill," Vaughn said. "Easy does it."

I sank back in my chair, stifling the explosion that was about to take place.

WELTY opened the suitcase. He took out of it what looked like

a model of a dirigible. It was about three feet long, beautifully

proportioned, with clean lines, and at the rear end it had a

system of elevators and rudders similar to those used in a real

dirigible. Jutting out on both sides were small engine mountings,

complete with tiny electric motors and propellers. Yes, it looked

like a model of a lighter-than-air ship, with some differences.

No control cabins were slung under it. Rows of tiny ports

extended along the sides. Apparently it was designed to carry its

passengers and crew inside the ship rather than in control cabins

slung under the vessel. It was beautifully made, I grant that

much. Real glass had been fitted into the tiny portholes, the

little doors were cunningly constructed, and it showed every

evidence of being a beloved and carefully built toy. It was

complete in every detail, including a wire launching rack into

which it fitted snugly.

Welty set it in the wire rack, flung the suitcase aside, took an electric extension cord out of his pocket, examined the switches on a control block built into the cord, and plugged one end of the cord into the model. The other end he plugged into a wall socket.

The door of the waiting room was still open and my secretary, her face white with anger, was standing in it.

Welty noticed her.

"Beat it, sis," he said. "This demonstration is strictly on the quiet."

She slammed the door so hard it made the furniture rattle. Welty calmly walked over and turned the key in the lock. "Can't have any spies getting a peek at this," he said.

"From the way you talk, you must think my waiting room is full of enemy agents," I said.

"Buster," he said, looking at me. "Spies are everywhere."

"My name is not—"

"Easy, Bill," Vaughn said softly. "If he can't produce, I'll help you throw him out, goatee and all."

"After you see what I have here, you'll change you tune, buddy," Welty said to him.

Vaughn had been taking his side! And this was what he got for it! The engineer's face turned red but he held his temper.

"I am going to demonstrate to you the first and only practical method of overcoming the influence of gravity," Welty said pompously.

"Huh?" I was so startled I could only gasp.

"You're going to see gravity nullified," Welty firmly answered, picking up the control block in the extension cord and putting a finger on the switch.

In this department, every dog gets his day, every idea, no matter how wacky, has its turn in court. If a man came in here and said he had built a ship that would fly to Mars, we would look at what he had.

"Watch closely," Welty said, closing the switch in the control block.

A faint hum came from the model.

Tiny lights appeared behind the portholes, giving the impression of a ship about to take off. The tiny motors began to spin their propellers.

Nothing else happened. The model didn't lift out of its cradle.

Perplexed, the inventor stared at it. "What is wrong?" he muttered.

Neither Vaughn nor I said a word. I leaned back in my chair and crossed my hands and began to twiddle my thumbs. Maybe I shouldn't have done that, but I couldn't help it. This guy had forced his way in here, he had insulted everybody, he had pompously announced he had something. Now let him produce. He wanted to show us. We were looking. We weren't seeing anything.

The sight of me twiddling my thumbs seemed to drive the inventor frantic. "I tell you it will work!" he shouted.

"That's up to you, butch," I said. "I'm looking. I'm waiting."

Welty jerked a screwdriver out of his pocket and began to poke into the model. Five minutes later there was a baffled look on his face, sweat was running down his cheeks, and the model was still sitting on my desk.

"If you'll just wait—"

"Take all the time you want," I said. Maybe my tone was off color but I meant what I said. I wasn't going to give him an opportunity to yell his head off that we hadn't given him a chance. In spite of his attitude, if he could make that model fly, we were willing to wait. He was still trying to make it work when the office inter-communicator buzzed. I snapped the switch.

"What is it?" I said.

"Mr. Edgar," my secretary's voice came from the box. "There are two men out here after Mr. Welty."

She sounded scared.

"After him? What do you mean?"

She didn't answer, but the doorknob rattled and someone tried to enter. Welty had locked the door. At a nod from me, Vaughn got up to open it.

"Is somebody after me?" Welty hissed.

Before I could answer he was shouting at Vaughn. "Don't open that door! If they're after me, they're spies! Don't let them in here."

He was too late. Vaughn had already opened the door.

A MAN in a white duck coat and white trousers stood there. It

was he who had tried the door.

"Mr. Edgar?" he said apologetically. "Sorry to disturb you, but we're from the Norton Psychopathic Hospital. We're looking for an escaped patient. Ah!" His voice changed as he saw Welty. Calling a command over his shoulder at another white-clad figure who was following him, he stepped into the room.

Welty took one look and dived toward the other door. Jerking the door open, he dived into the hall. The two white-clad hospital attendants ran after him.

It was like a chasing scene in a Marx movie. All I could do was sit there and gape. Vaughn, a silly grin on his face, had backed against the wall. He was gaping too.

There was a commotion out in the hall, sounds of a struggle. It soon ended. One of the hospital attendants came back to the door.

"We put him in a strait-jacket," he said, wiping his forehead. "Sorry if he disturbed you. He escaped several months ago and we've been trying to find him ever since. Somebody who used to know him saw him entering your office a while ago and tipped us off, which is how we got here so quickly."

"Er—thanks," I said. "He disturbed us a little but no real damage was done. What's the matter with him?"

"He thinks he is an inventor," the attendant said. "Harmless, of course, but you never can tell when one of the harmless ones will blow his top, which is why we have been so anxious to capture him." He shook his head a little sadly.

Welty was a nut out of an insane asylum, an escaped psychopath running around on the loose!

"WELL," Vaughn sighed, sinking into a chair after the hospital

attendant had gone. "There is always something happening around

here. If we're not looking at a perpetual motions machine, we're

looking at something equally bad." He glanced at me. "You could

do with a drink," he said.

He was right about that. He got the bottle out of the closet. It was good whiskey. We each had one, straight.

"This is the last time any inventor is going to get in here with a model!" I said emphatically. "Some of these days some nut is going to bring in a model of a brand-new bomb he has invented—"

"—And the damned thing is going to work!" Vaughn supplied.

"And we are going to get ourselves blown to hell and gone!" I ended.

At least a dozen times we had decided that no inventor with a model was going to get into the building. We never stuck to our decision, for the obvious reason that an inventor without a model to demonstrate is like a duck out of water—all he can do is quack.

"Incidentally, what became of Welty's model?" Vaughn asked.

For the first time I noticed it was no longer on the desk.

"Didn't he take it with him? What's the matter, Jim? What's wrong with you?"

Vaughn had half risen out of his chair. There was a strained expression on his face and the blood had drained out of his cheeks. He looked like a man who was seeing a ghost.

"L-l-look, Bill!" he stuttered.

The left end of my desk was about a foot from the wall. Directly in front of the desk was a bank of filing cabinets, which effectively hid the opening to the left of the desk from anyone looking in the door. Vaughn, his face ashen, was pointing toward this space.

I took one look and my heart jumped up into my mouth. Welty had placed his model on the floor to the left of my desk. Apparently he had utilized our preoccupation when the hospital attendants had entered to hide his invention. I hadn't seen him hide the model, and neither had Vaughn, but the fact remained that he had hid it. There was nothing startling about this.

The startling fact was that it hadn't stayed where he had put it!

Tugging at the electric cable that fed current to it, tiny motors whirring, it had risen to the level of the top of the desk. It was still rising! Slowly, a fraction of an inch at a time, it was going up. Fighting against the lines of gravity, it was rising into the air. Up, up! The transformers hidden within it were humming, the lights behind its tiny portholes were glowing.

Without wings, it was rising like a dirigible!

"The damned thing works!" Vaughn gasped.

It hadn't worked, when the inventor had tried to demonstrate it. But it was working now. Apparently, when he had hidden it, he had either forgotten to turn off the current or had deliberately failed to do so. Whatever had happened, the model was working. It was rising into the air.

My mind jumped the track. Mentally I was simply not prepared to accept the evidence of my own eyes. My first dazed impression was that I was the victim of an illusion. But both Vaughn and I would not be victims of the same illusion. Welty had said he was going to demonstrate a practical method of overcoming the effect of gravity. When his invention had not worked, and when it was revealed that he was insane, my reaction had been to decide that it would never work. I make no apologies. Anybody else in my position would have reacted the same way.

But his invention was working!

"Do—do you think it's a trick?" Vaughn stammered.

"What kind of a trick?"

"Maybe the model is filled with gas. Maybe it only weighs a few pounds and is lifted by gas. That must be the answer," he decided. "Welty must have built a very light model of a dirigible and filled it with gas. To his addled mind it may have seemed that he had really discovered a method of counteracting gravity. Probably those tiny propellers actually lift the model, and if we turn off the current—"

He was groping for an explanation that would satisfy his engineering mind. His explanation sounded logical to me. I've seen plenty of model airplanes that would fly. Some of them are fitted with tiny gasoline motors and they really get up and go. If this dirigible model had enough gas in it to almost balance the few pounds it must weigh, then the little propellers would provide enough lift to get it into the air.

Vaughn walked around the desk, shoved the filing cabinets to one side, and picked up the control block that held the switch.

"This will prove it's a trick," he said, opening the switch.

The model was about three feet higher than the desk. It was still rising slowly, still fighting gravity, still struggling to get higher into the air, when Vaughn snapped the switch.

With a thud that seemed to shake the whole building, the model nosedived straight down and hit the floor. It landed with a resounding thud that rattled the windows and shook the furniture. Vaughn looked at me. His lips were parted and he seemed to be trying to speak but he couldn't say anything.

I knew what he was thinking. If that model had been filled with gas, if it had been just a toy, it would not have fallen so rapidly. It would have floated down. And it would not have made much noise when it hit.

Vaughn bent over and picked it up. Tried to pick it up. I saw his back muscles bulge through his coat. He lifted it all right, but not easily.

"Holy cats!" he whispered huskily. "It must weigh a hundred pounds. Bill—"

BUT I was already buzzing the interoffice communication,

snarling at my secretary. "Get me the—what was the name of

that place those hospital attendants came from?—Get me the

Norton Psychopathic Hospital! And burn up the wires doing it!

This is an emergency!"

I wanted to talk to the head man at that hospital. I wanted to talk to him worse than I ever wanted to talk to any man! While my secretary looked up the number and put the call through, Vaughn looked at me.

"Bill," he whispered. "Insane or not, Welty has actually discovered a method of counteracting gravity. No gas would lift a model that weighs as much as this one weighs. These little propellers won't do it. We saw it fly. We can't deny that it works. Bill, do you know what this means, if all the technical details can be worked out? Do you know what it means?"

"Hell, yes, I know. It means there won't be any more of our battleships on any ocean. We'll put wings on them and fly them to Tokyo through the air. We'll tell the Japs we're coming to pay them back for Pearl Harbor, only we'll tell them in advance, and defy them to stop us. We'll tell the Nazis to start looking for holes they can crawl into and pull in after them, because we're going to pay them a visit, with battleships in the sky. We'll tell Mussolini to take a nose-dive head first off his balcony, because if he's still around when we get there, he'll learn what trouble really means. We'll—"

I was probably half crazy. And so was Jim Vaughn. There was a war going on, a dirty treacherous war, and we were going to win it, sure, in time, but with Welty's invention fighting on our side, we were going to win it quickly. With an effective method of counteracting gravity, airplanes wouldn't have to depend on wings. Without gravity holding them down, they could go straight up, high, high, as high as the sky. They could be made the size of zeppelins, but instead of having an outer surface of rubberized fabric that a bullet tore to pieces they could be armored with inches of steel, armed with heavy guns, made impregnable and irresistible.

Welty's invention would win the war!

And after the war was over, well, it would change the face of the earth. We would fly to work and fly home. We would fly down to Florida for a vacation in the winter and up to the north woods for a vacation in the summer. We might even build floating cities in the sky. Tennyson's "—pilots of the purple twilight dropping down with costly bales," would come true in a way the poet never dreamed. And, with no gravity to fight, why couldn't we build moonships? There wasn't any reason. We would be able to build moonships. And after that, ships to reach the stars that glitter in the sky!

The invention of a lunatic might easily reshape human destiny!

THE phone buzzed. It was my secretary. "I have the hospital

for you, Mr. Edgar."

A dry voice came over the wire. "This is Dr. Gerson of the Norton Psychopathic Hospital. What can I do for you?"

I told him who I was. "When your men return with Welty I want you to give him the best possible care. And I want you to let no one talk to him until I get there. This is of the utmost importance."

"Welty?" the doctor said. "Welty? I don't seem to recall the name. Is he one of our patients?"

"He was, until he escaped several months ago. Richard J. Welty. An inventor. Two of your men just caught him here in my office. They're on their way back to your hospital with him right now."

"Welty?" the puzzled doctor said. Then his voice changed. "Oh, yes, I recall the case now. He was here for a short time as a private patient. Our observations indicated he was suffering from a rare psychosis the outward manifestation of which was a dual personality. Nothing dangerous, however. We discharged him several months ago."

"You discharged him? I thought he escaped."

"Not at all."

"But listen," I protested, "if he didn't escape, why did your men come in here and grab him? Weren't they looking for him?"

"Certainly not," the irritated doctor said. "As for two of our men apprehending him, you must be mistaken. In the event of an escape, which is unlikely, we rely on the police to return the patient to us. We have no facilities for apprehending escaped patients."

This made something a little bit less than sense to me. "Listen," I shouted, "What kind of a run-around are you trying to give me? Two men from your hospital were in my office not fifteen minutes ago. They were wearing hospital uniforms, they grabbed Welty, put him in a strait-jacket, and said they were from your institution. What it this anyhow?"

"I'm sure I don't know what it is," the doctor said. "I would suggest the possibility that you are the victim of a practical joke. Certainly no men from this hospital did what you say these two men did."

"But I saw them do it!" I yelled. "They told me they were from Norton Psychopathic Hospital."

"Then they were lying to you!" the doctor snapped. "They weren't from this hospital, and from your description of their method of procedure, I doubt if they were from any hospital. Now you have wasted enough of my time."

Click! The receiver went back on the hook. The line went dead.

"What is it?" Vaughn demanded. "What did the doctor say?"

I told him what the doctor had said. His eyes widened. "Spies!" he gasped. "Those two men must have been spies. They must have known what he was working on. He got away from them long enough to get here but somehow they must have managed to follow him. They kidnapped him right from under our noses!"

Welty had been afraid of spies. Before the men had entered, he had said they were spies. We had thought he was cracked. But we were the ones who were cracked!

"Holy cats!" I yelled. "Get down to the front door and talk to the guards and find out which way they went. I'll put in a police call to pick them up. They didn't leave here more than fifteen minutes ago. They can't have gotten far—"

BUT Vaughn was already out of the room. I waited only long

enough to put in a call to the police department and to call

special guards to my office before I followed the engineer.

"Guard this model," I said to the husky men who answered my ring. "At all costs."

They nodded. The model would be guarded. As long as we had it, we could observe it in operation, disassemble it, study it, learn what made it tick. But we wanted the inventor too.

When I got to the front entrance I found Vaughn frantically questioning two guards.

"Yeah, I remember those two fellows from the hospital," one of the guards said. "They said they were looking for an escaped lunatic. Yeah, they got him all right. Put him in an ambulance right in front."

"Which way did they go?" Vaughn asked.

The guard nodded to indicate the direction in which the two spies had fled.

Before he could speak again, a squad car rolled up. The uniformed officer at the wheel leaned out. "You the guys that put in the rush call?" he asked.

He listened carefully to what we had to say. "Jump in," was all the comment he made.

The radio in the squad car let go with a blast. "Calling all cars. Suspicious ambulance moving at high speed along Maryland Avenue. Arrest and detain occupants—"

"Here we go," the driver said. He shoved down on the accelerator and the car almost jumped out from under us. We made the turn from the driveway into the street on two wheels. The officer sitting beside the driver turned on the siren. Here we went!

Judging by the startled looks we got, a lot of Washington residents must have thought an air raid was on. If we failed in our mission, if the Axis agents succeeded in spiriting Welty away and forced him to reveal the secret of his discoveries, there would be air raids on Washington. And on New York, and Chicago, and Los Angeles. Air raids such as the world had never seen before!

"There they go!" the driver suddenly said.

Far ahead of us, I caught a glimpse of an ambulance. A cop on a motorcycle was trailing it and as we watched, a squad car roared out of a side street and joined the chase. The driver of our car mashed the accelerator all the way to the floorboard. A puff of smoke leaped from the back door of the ambulance, stabbed toward the motorcycle.

The motor bike veered abruptly, skidded as the rider frantically tried to right it. Then it went out of control and dived headfirst across the sidewalk and through a show window. The rider went with it.

The driver's face went grim. The other officer reached down and picked up a tommy-gun. Neither said anything.

"We want their captive alive," I said.

THE ambulance swung out in a wide turn and roared out of sight

down a side street.

The squad car that had taken up the chase ahead of us burned rubber as it made the same corner. Then we took it. Our car leaned like a yacht in the wind. Rubber screamed. But we made the turn.

Ahead of us the ambulance had already stopped. Two white-clad figures were leaping around. They jerked open the back door of the ambulance, yanked out a man in a strait-jacket. Half dragging him, they ran toward a large building that looked like it had once been a garage.

"They've probably got a hideaway in there," one of the cops gritted. "They may be able to give us the slip. Well, we'll see!" He was the one with the tommy-gun. He kicked open the door of the car and leaped out. The driver grabbed a couple of tear-gas grenades, and followed.

The first squad car had already stopped. Two officers with drawn pistols leaped from it.

Dragging Welty, the fake hospital attendants vanished into the building. A heavy door slammed behind them. A small peep-hole popped open in the door, a gun was thrust through it, and a barrage of shots smashed at the police.

The cops ducked for cover. But they didn't retreat. Keeping out of sight as best they could, they rushed the door. A machine gun blasted at the peep-hole and the pistol poking through it was abruptly withdrawn. A cop ran forward, shoved a tear-gas bomb through the hole. No more shots came from within. The tommy-gun was turned on the lock. Under the blasting stream of slugs, the lock gave way.

The police kicked the door open.

There was tear-gas inside. The cops didn't have masks, but they went in anyhow, shooting at anything that moved.

"Come on," said Vaughn.

The gas fumes were blinding in there, but we went in. I got there just in time to see the barrel of a gun come down with resounding force over the head of a fake hospital attendant. He hit the floor and didn't move after he hit. The other man in white was already on the floor. A bullet had caught him exactly between the eyes.

"This the man you're looking for?" an officer coughed, pointing to a figure in a strait-jacket.

Welty was moving. He was trying to sit up!

"He's alive!" Vaughn shouted thankfully.

WE carried him outside, jerked off the strait-jacket. A quick

examination disclosed no sign of injury. Tears were running down

his face and he was coughing from the effects of the gas but he

wasn't seriously hurt.

"We've got him!" Vaughn exulted. "We've got the man who knows how to whip gravity!"

"Please don't hurt me," Welty begged. "I won't do it again. Please don't hit me. I won't do it again—"

"We're not going to hurt you, Mr. Welty," I assured him. "You can be certain of that. We're friends."

He wiped the tears out of his eyes and looked up at me. "That's nice," he said hesitatingly. "I'm glad you're not going to hurt me."

Bewilderment appeared on his face as he looked at me. "Who are you?" he said. "I don't know you. Who are you?"

"You know me," I said blankly. "I'm William Edgar. I'm one of the men who looked at your invention today. I'm from the War Department. You brought your invention in for me to see. You remember that, don't you?"

I thought possibly he had suffered a slight concussion.

He stared hungrily at my face. "I never saw you in all my life," he whimpered. "I don't know anything about any invention. I haven't been within miles of the War Department—"

"You—" I caught myself, looked closely at him. This was Welty all right. The beard, the sideburns, the clothes, identified him beyond the chance of a mistake. But he had changed. When he had first entered my office, he had been a blustering, domineering, to hell with you individual, the type that crashes parties, that orders waiters around, that won't take no for an answer. Now, he was frightened, timid, scared. A complete change had come over him. He trembled when he looked at me. He seemed to have no will of his own.

"He's stalling," Vaughn said vehemently. "He remembers all right. He just doesn't want to talk. He knows that we have discovered the value of his invention and he is trying to hold us up for a fancy price." Vaughn turned to the inventor. "You won't get away with it, do you understand? We'll pay you whatever you demand, but you've got to come clean with us. You've got to give us the theory back of your invention, the technical details—"

The inventor cringed away from him. "Please," he begged. "I don't know what you're talking about. If I've done anything wrong, I'm sorry."

He began to cry!

Vaughn looked worried.

Was Welty stalling? Was he putting on an act? Was he trying to gouge us?

There was only one way to find out.

I SENT Vaughn back to my office.

Borrowing a squad car and two husky policemen as escorts, I took the inventor to Norton Psychopathic Hospital. Dr. Gerson listened carefully to what I had to say. Then he examined the inventor with great care. When he had finished he drew me aside.

"Welty is not attempting to deceive you," he said.

"But Dr. Gerson," I protested. "He surely must remember being in my office."

The physician shook his head. "I'm afraid not," he said. "I think he has no memory of ever having seen you or been in your office. We have here a case of a type of dual personality, a sort of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde situation. Welty has two personalities, each occupying different sections of his mind. In one personality, he is blustering, domineering, boastful—and, if what you say is correct, one of the greatest inventors who ever lived. In his other personality, he is timid, meek, scared of a shadow, and without enough mechanical aptitude to change a tire! When he came into your office, and unquestionably for some time prior to that, the inventive part of his mind was uppermost. But the shock of the kidnapping, the chase, brought his other personality to the surface. He can have one personality, or the other. Not both at the same time. The things he does as Dr. Jekyll he will not remember as Mr. Hyde, and vice versa. So he does not remember his visit to your office, nor does he remember anything about his invention."

This doctor seemed to know what he was talking about. I couldn't argue with him about his own field.

"But will he change back?" I asked. "Can you change him back? Can you fix him up so he will remember his invention? This is desperately important—"

"I'm sorry," the doctor shrugged. "What you ask is beyond medical science. He may change back. He may not. But I can't force him to change back, and neither can anyone else."

That was that. Welty's secrets were locked up in Welty's mind where nobody could get to them!

"Well, anyhow, we have the model of his invention," I said. "We'll be able to work from that."

It was comforting to know we had the model. Vaughn was a first-class engineer. He would be able to determine the method by which the model worked. He would have help, all the help he wanted, the best engineering minds in the United States to work with him.

When I returned to my office, I found it jammed full of men. Engineers and army officers. The sight sent a surge of fright through me.

"What's wrong?" I demanded. "Is the model gone?"

Vaughn looked around at me. His face was tense and haggard. "It's here all right," he said, pointing to where it rested on my desk. "But—"

"But what?"

"But it won't work any more," he faltered. "When it fell, something must have broken inside it. I've turned current into it a dozen times. It hums, but it won't rise. It's broken—and we can't fix it..."

AND there the matter rests today.

The model was broken when it fell. Every effort had been made to correct the difficulty, without success. Sure, the engineers—the best in the country—have disassembled it, taking pictures of every step in the process so they will know how to put it together again. They've torn it down and put it back together again a dozen times. They've studied it from every angle and have spent haggard weeks trying to develop the theory behind it.

Now and then they swear at Vaughn and me because we insist we saw it fly. They say it can't fly. But we saw it fly and we stick to our guns.

There is no question but that in time they will discover what makes it tick. There are several strange and unusual crystals buried in the tiny instruments inside the hull. They resemble the crystals used to maintain frequency in radio transmitters and the engineers think the crystals are the key to the whole invention. But they haven't been able to analyze the crystals. They get hints, clues, elusive indications, but nothing that can be tied down definitely. They have discovered just a little of the underlying theory, enough to know that it operates on a principle entirely new to science. They'll lick the problem, in time.

Meanwhile, in a carefully secluded institution, Welty is being guarded day and night. He is having the best possible care. Everything that can be done for him is being done. But in spite of all the doctors can do, he remains a bewildered, frightened, cringing mouse of a man. The doctors say that if ever he starts to bluster and to raise hell in general, it will be a good sign. But he hasn't started blustering, yet.

And Jim Vaughn. Poor devil! He is the man who opened the switch that let the model crash. No one blames him for what he did. Anybody else would probably have done the same thing. But he blames himself. He has had a cot moved into his laboratory and he uses it to snatch a couple of hours sleep every night. The rest of the time he works on that model.

Some day he will discover how it works. Or some day Welty will come blustering into the lab and tell him how it works. When that happens, look out Tokyo.