RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Probably the very soul of the wife he had just murdered," is the

solemn reply of science after a series of remarkable experiments.

"At first an indistinguishable shadow seemed to be gathering just above the body, rapidly assuming the outlines of the human form. The features bore the likeness of the dead. The delicate, clear, and ethereal being floated gently in the atmosphere—floated through the air a moment, and then, as if impelled by some attraction, moved like a vapory mass toward a half-open window."

—From the Confession of Professor Berrich.

ADOLPH BERRICH, a gaunt, emaciated maniac, was captured by

the sheriff and a posse last month on the prairie, nine miles

from Colorado Springs, Col. To the physician at the County Gaol,

where he was first taken, he immediately became an object of

intense interest by revealing himself as a student of advanced

physics and chemistry.

Fragmentary utterances indicated further that the new inmate had fled from Boston, Mass.; that he was Professor Adolph Berrich, and that he had killed his own wife in the interests of science. In a rambling way he has described an experiment with a fluorescent screen, ultra-violet rays, and other apparatus, and a human soul floating away.

Berrich's statements were so remarkable that a search was made of the cave in which he had been leading a hermit's life for years, in the hope that something more tangible might be found of the soul-seeing apparatus to which he referred so often.

The searchers found nothing of importance but a very lengthy manuscript, very illegible at times. Though the document is unsigned, its author is in all probability Professor Berrich, for it relates in slightly less fragmentary form the details of the ghastly scientific experiment on which the mind of the maniac is forever dwelling.

Considered alone as an unsubstantiated document, the curious manuscript of Professor Berrich is of little apparent value, and may be dismissed as the irresponsible ravings of a lunatic. But it becomes of tremendous importance when considered in connection with the experiments which have just been completed by Professor Elmer Gates, the Washington scientist. By the use of ultraviolet rays, a fluoroscope, and other apparatus, which Berrich ramblingly describes over and over again, day after day, Professor Gates claims to have duplicated the soul-seein g experiment of the mad Professor Berrich. He used a dying rat in the final and most successful test, and detected, it is declared, a shadow which passed over the specially-prepared screen and faded away as the little animal died.

Berrich asserts that he saw the soul of his own wife in his experiment. The discovery by the Washington scientist indicates that it was not impossible for him to have done so.

"SO it seemed to me that what would be most worth knowing on this earth would be whether there is or is not any hereafter. My training in the sciences naturally prompted me to scientific investigation, but for years my results were absolutely negative.

"Then, years ago, I was convinced that science had no way of solving the subject—and, indeed, it hadn't at that time. I left the United States, and spent several years in other countries. Into all those relics of superstition known as the black arts I delved.

"After seven years I fell in love in Paris, and married a beautiful but vain girl much younger than myself. I resolved and promised to give up my crazy ideas and live only for the present, as all animals and most people do.

"We were quite happy for six mouths, which we spent in Europe. Then my old desire crept back upon me.

"Every night my wife knelt by the bedside and prayed. At first she prayed out loud for her dead parents and for herself and for me. It was no use to argue with her that there are no trustworthy evidences of a soul, and that the hereafter is a myth invented for simple minds. She had to admit the strength of my arguments, offered none in return, but kept on with her prayers.

"As soon as the prayer was over, she dropped quickly to sleep. I, however, was doomed to follow out till the small hours the chain of doubts and clues engendered by her prayers."

Several lines are partially obliterated by the weather at this

point, but the sense is evident from the remaining words.

"From that moment I was possessed of an idea. A fixed idea, psychologists call it. I recognised it, fought against it, criticised it—and the insane do not criticise their ideas—so I was not insane. Yet the idea grew upon me each night that if I could kill a human being in the right way and be all prepared, I might see the human soul.

"If I could but catch a glimpse of the soul as it forsook the dead body, my doubts and misery would be at an end. I felt that my life would be peaceful ever after, and that I would atone for the murder by spreading the truth of immortality to all the world. That would surely be worth one life."

WEARY of what he had endured in Old World travels, this

narrator of a revolting crime turned homeward, "but better had I

drawn lessons from the legends of Vanderdecken, the Flying

Dutchman," he says, "or Abasuerups, the Wandering Jew, cursed

with perpetual youth and ever seeking an elixir of death.

"In my sleepless nights the temptation was terrible to slay the woman who lay breathing silently beside me. She, with her prayers, was half the cause of my misery.

"At last I saw that I must eventually yield to my obsession, and determined to prepare for it. Science had progressed mightily in the eight years since I had relinquished it. Great discoveries were made with the wide range of light rays on the invisible side of violet. From the little octave of light visible to the eye they run up and up like the notes of a piano, only to infinitely higher pitches.

"I had long been anxious to experiment with these new rays. On our return to Boston I fitted our house up with many instruments.

"My wife, a sweet, but unintellectual and vain person, showed an antipathy to my work. She refused to enter my laboratory, and seemed to shudder at my harmless fluoroscope and light bulbs.

"One night my fixed idea rose in its gradually acquired might, and took command of me. My wife had just returned from a fashionable ball.

"She complained of a terrible headache, and accepted my offer to relieve it. I gave her a hypodermic of morphia.

"I deliberately gave her an overdose, but not a fatal one. The effects of the drug came on instantly, the headache passed, she thanked me drowsily, and was soon insensible, lying in her ball gown breathing heavily.

"With elaborate care I brought in my instruments from the laboratory, and arranged them. My heart beat as it never beat before. It was not a palpitation, but a strong surging beat which sent the blood to my brain in a steadier, stronger stream than usual. My faculties seemed exceptionally acute, as well they might be, for I felt that I was to be the first scientist and perhaps the first man to see a human soul.

"At last the instruments were arranged, tested; and found to be working perfectly. Behind me were the tubes emitting the ultraviolet light. They were placed behind me because I believed that I could see the soul in reflected light as it really looks, and not a mere shadow as it would appear between me and the light. My fluorescent screen had a lens attachment for focusing an image, which I believe, was an entirely new idea."

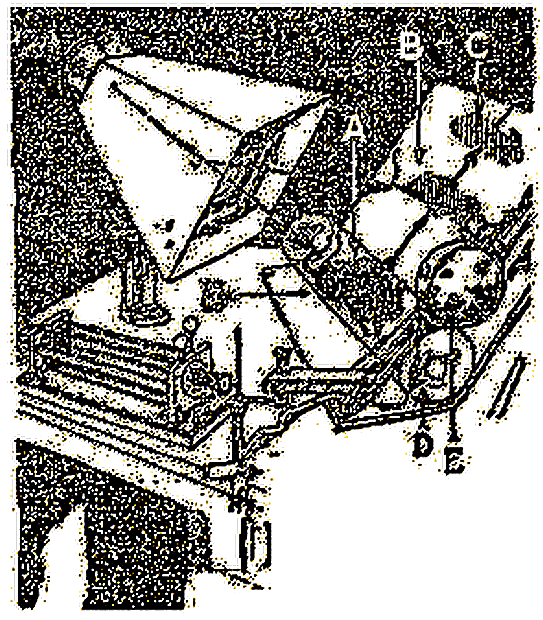

Prof. Gates' apparatus through which he claims he saw the soul leave the body of a dying rat.

A. Shadow which exists only while there is life.

B. Upon death of a rat a faint shadow is

seen moving across the sensitised screen.

C. Shadow loses strength as it nears top of screen.

D. Hermetically sealed glass tube, in which rat was placed to die.

E. Apparatus which generates the new electrical rays.

"I opened a secret drawer in my secretary and took therefrom the most deadly of all silent agencies of death, a hypodermic syringe filled with cyanic acid, two drops of which injected into the veins produces instant death, leaving no purple blotches or traces of any kind.

"At first an indistinguishable shadow seemed to be gathering just above the body, rapidly assuming the outlines of the human form, and most perfect in its symmetry. The features bore the likeness of the dead, and were beautiful beyond description. The delicate, clear and ethereal being floated gently in the atmosphere with eyes closed, until the process of nature seemed complete, when they opened and a sublime intelligence passed over the face. It floated through the air a moment, and then, as if impelled by some attraction, moved like a vapory mass towards a half-open window, passed out, and was gone for ever from my sight.

"The eyes seemed to look toward me an instant. The expression changed. Not anger, nor reproach, but utter amazement, was depicted on that filmy countenance as it drifted out of range of my screen.

"For some time I stood like one stricken dumb. The enormity of the crime I had committed came like an avalanche upon my brain. Again and again I called my wife's name, and only the echo of her wailing voice answered me.

"I destroyed all evidence of my guilt, and fled from the city of Boston, away to the mountains of the West. Here for two years I have lived in seclusion, many times meditating my own life, but always having desisted from my purpose because I wanted first to prove what sI have all this time been trying to solve:

"Is death but the beginning of life?

"My mind is weak and fogged as I write this, and my memory bothers me. I am probably going insane, if I am not already so.

"Well, so be it. I am glad to experience insanity, too: in fact, I will put off death and see what it is like."

(The strange manuscript ends at this point. There is no signature, and it is thought there may possibly have been more.)